- Trump’s 2024 Coalition: Unified multi-faith conservatives including evangelicals, Orthodox Jews, Catholics, and some Muslim voters around opposition to Progressive social changes.

- Domestic vs Foreign Power: Trump wields dominance in headlines and global affairs while facing internal movement instability from ideological factions.

- New Right Divide: A younger, digital-first generation claims “MAGA” no longer aligns with “America First,” elevating figures like Nick Fuentes beyond Trump’s control.

- Ideological Drift: Online influencers have co-opted populist discontent toward anti-establishment narratives that reject alliances and liberal internationalism.

- Strategic Tensions: Trump’s nationalism and China containment clash with Elon Musk’s global tech vision, especially through X’s amplification of anti-coalition signals.

- Tucker Carlson’s Role: Once a loyal amplifier, Carlson now promotes anti-Israel, anti-neocon narratives that threaten evangelical and Jewish support within Trump’s base.

- JD Vance Alignment: The vice president’s ties to Carlson and postliberal intellectuals blur the ideological boundary between Trump’s coalition and the emerging anti-alliance right.

- Coalition Fragility: Loss of evangelical-Zionist support due to antisemitic and anti-Israel currents imperils the broad majority Trump needs to sustain a China strategy.

[

](https://archive.is/o/7bOzT/https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news)

Giant Abroad, Midget at Home

[

Tablet Logo.

](https://archive.is/o/7bOzT/https://www.tabletmag.com/)

[

](https://archive.is/o/7bOzT/https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/news)

JANUARY 2026 PRINT EDITION

Giant Abroad, Midget at Home

Why the Trump coalition is cracking up

by[

Michael Doran

](https://archive.is/o/7bOzT/https://www.tabletmag.com/contributors/michael-doran)

January 05, 2026

ILLUSTRATIONS BY VICTOR JUHASZ

ILLUSTRATIONS BY VICTOR JUHASZ

At the start of 2026, Donald Trump should have the wind at his back as he sets out to assure America’s future.

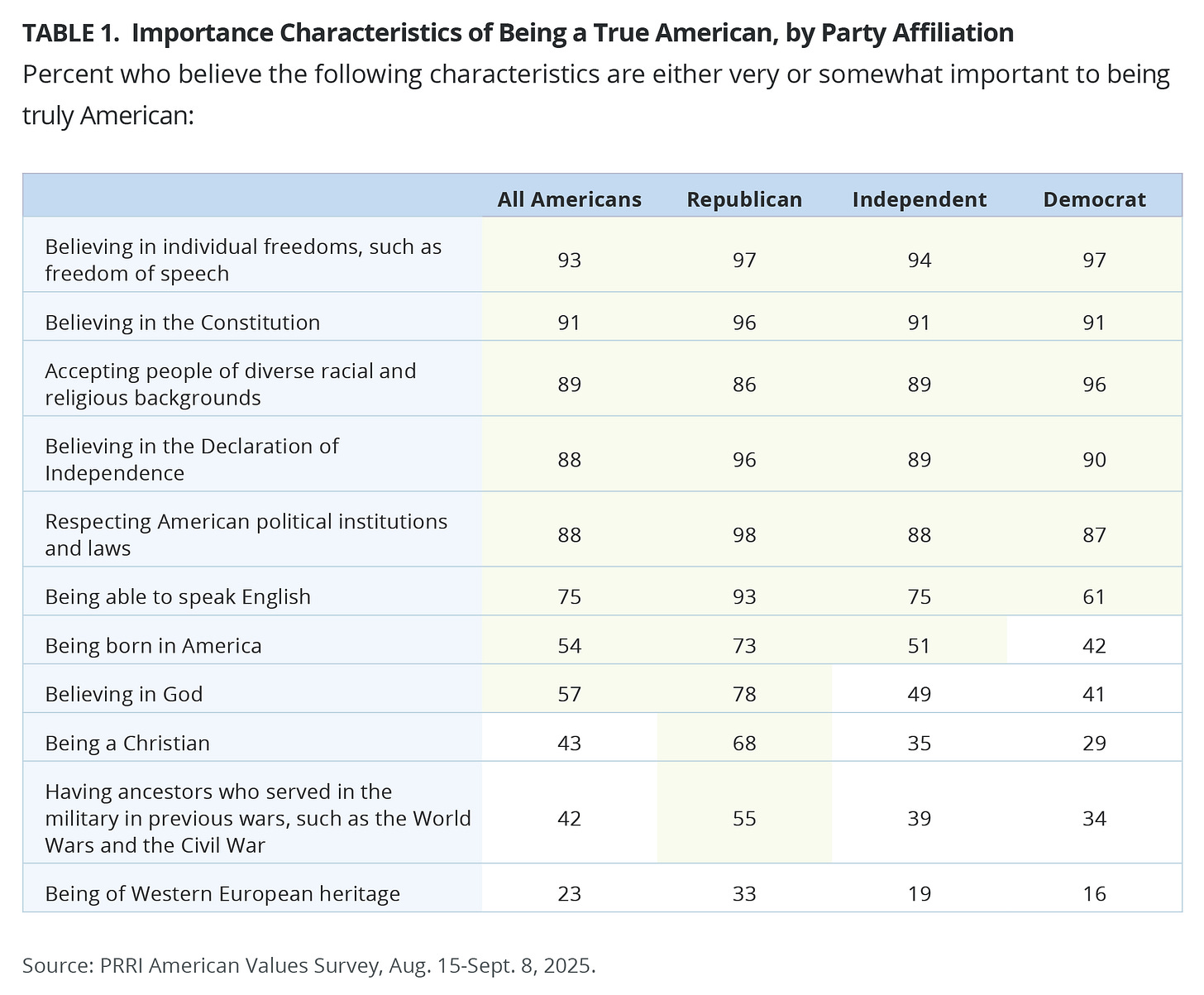

For his recent election, he assembled the broadest multi-faith conservative coalition in modern American politics. A twice-divorced casino magnate who bragged about his sexual exploits to interviewers, rarely attended church, and once identified as pro-choice hardly embodied the “family values” that had defined the Religious Right since the late 1970s. Yet despite violating the moral norms religious voters championed, he drew more unified, enthusiastic support from them than any Republican in the modern era. Church-going white evangelicals gave him historic margins, but so did Orthodox and observant Jews. Traditionally Democratic Catholics swung hard to the GOP. And in a twist almost no one predicted, in 2024 thousands of Muslim voters in Michigan—long considered a Democratic lock—crossed over to vote for him.

While he was attracting religious voters, he was also pulling in millions of secular or nominally Christian Americans who never open a Bible. What unified these constituencies was a shared belief that the Progressive assault on traditional norms had spun out of control. By driving anything sacred out of public life, Progressivism had robbed the country of its moral north star.

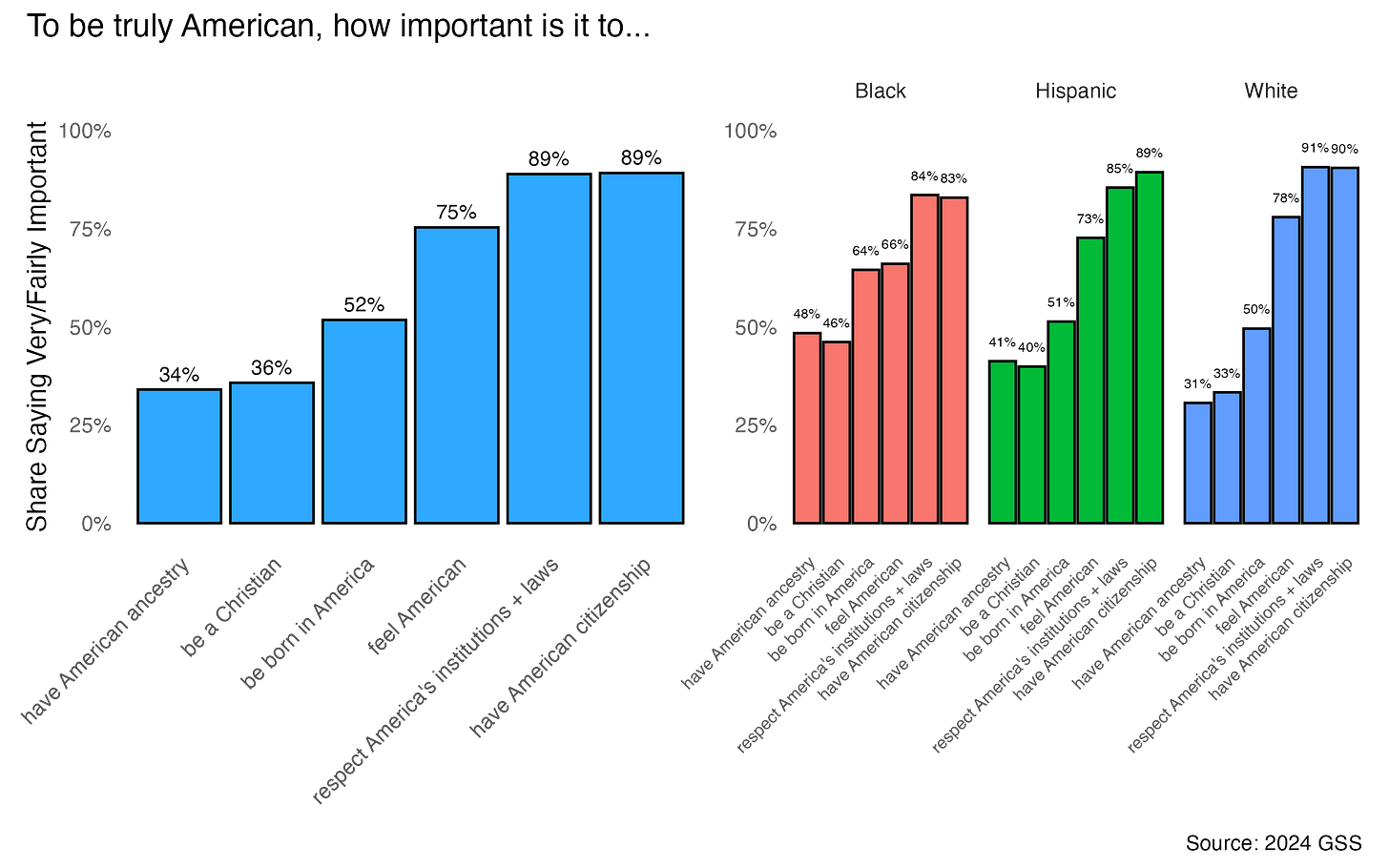

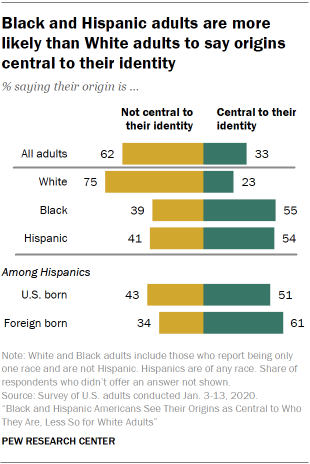

This appeal to disaffected religious voters gave Trump his sharpest weapon against the Left’s identity politics. Democrats assumed Black, Hispanic, and female voters would always vote their race or gender rather than their religious convictions. Trump’s “God bless America” populism broke that logic. By casting himself as the defender of embattled believers against secular elites rewriting biology and dismantling traditional family life, he spoke directly to socially conservative Black churchgoers, evangelical and Pentecostal Latinos, and even some traditionalist Muslims who cared more about faith and family than progressive orthodoxies. His message crossed ethnic lines and peeled off voters the Left assumed it owned forever.

This coalition was Trump’s breakthrough. For all its novelty, it stood in a recognizable Republican lineage. Eisenhower and Reagan had both shown that a broad, nonsectarian language of faith could bind religiously and racially diverse Americans into a single political community. Trump replayed that winning tune in a populist key—offering not theological precision but an expansive moral vocabulary in which disparate groups could locate their place in the national story. It made him electorally viable and gave him the possibility of building a durable governing majority.

Now, as the first year of his new term draws to a close, Trump stands at the height of his formal power. Abroad, he has smashed Iran’s nuclear sites; forced a ceasefire in Gaza; hit China with tariffs; wrung major new defense-spending commitments out of Europe; and inserted Washington into the Ukraine war in ways that are drastically altering the geometry of the conflict. Friends and adversaries alike track his moods by the hour. At home, he dominates the headlines, bends government agencies to his will, puts previously impervious elite institutions onto the defensive, and more.

And yet, at just this moment of triumph, Trump seems to be losing control of his own movement. The challenges—some around foreign policy, some around domestic issues, some related to messaging in general—at first seemed disconnected. But on closer inspection, one can see a common thread running through them—a line of attack aimed squarely at the heart of his legacy.

“MAGA” and “America First” once functioned as synonyms—two labels for the same revolt against the Progressive orthodoxy of an entrenched elite that was unresponsive to the voters. But inside Trump’s base, a rising faction now insists the two are diverging. In their telling, Trump’s second-term agenda has drifted from first principles.

They frame this drift as the betrayal of a younger, angrier, and more ideologically committed generation. Trump’s instincts still belong to the media world of the early 2000s—broadcast TV, cable warriors, mass audiences. The insurgents come from an entirely different universe: livestreamers, meme ecosystems, encrypted apps, and anonymous digital tribes that define themselves against every establishment, including the Republican one Trump reshaped in his own image.

The cleanest measure of this distance is the figure they have elevated as a kind of mascot: Nick Fuentes. A racist, antisemitic, misogynistic admirer of Hitler and Stalin, Fuentes should be untouchable in any serious political movement—yet within the Gen Z New Right he is wildly popular, a totem of defiance for young men who think the system has written them off. Trump has no direct connection to him and no desire for one; the two occupy entirely different cognitive worlds.

“Behind a facade of loyalty, Carlson has called Trump ‘a demonic force, a destroyer’ and admitted, ‘I hate him passionately’”

But Fuentes’s star is rising in the ecosystem orbiting MAGA. Tucker Carlson hosted him. Other major online personalities rallied to his defense. And when Kevin Roberts, president of the Heritage Foundation, initially intervened to defend Carlson’s interview with Fuentes rather than recoil from it, he signaled that the contamination had spread far deeper into the institutional right than anyone imagined. When asked to comment on Carlson’s interview with Fuentes, Trump declined to take a position—an omission that underscored how far this milieu sits from his instincts and how little control he exerts over it.

Many observers still imagine this “America First” revolt as a spontaneous, bottom-up development—young men, alienated by economic and cultural collapse, simply “discovering” isolationism and conspiratorial politics on their own. That story is half-true—at best.

What actually happened is simpler and more deliberate. For two decades, progressive institutions racialized every public discourse, taught an entire generation of boys that their skin color made them inherently suspect, and demonized the traditional markers of male identity—strength, duty, family, faith, nation—as forms of toxic oppression. The result was not a political movement but a widespread, inchoate mood of distrust:

Nothing works anymore.

The system is rigged.

The people in charge hate us and always will.

Everything they tell us to care about—democracy abroad, allies, global leadership—is just another way to bleed the country dry.

That mood is real. It is raw. But it is also politically malleable.

It could, in principle, be channeled toward Trump’s renewal project—toward a restoration of American vitality sustained by a broad, multi-faith coalition and a repurposed alliance structure aimed at containing China. Instead, an entire pyramid of online influencers—podcasters, meme-lords, streamers, and anonymous posters—has spent Trump’s first year pushing it in the most destructive possible direction.

At the very top of that pyramid sits Tucker Carlson. Show after show, he takes that mood and harnesses it to a comprehensive indictment: not just of the progressive elite, but of the entire postwar order, of alliances themselves, of the very idea that America should remain strong abroad in order to remain free at home. This broader New Right is not uniformly racist or antisemitic, but it is now uniformly shaped by the story these people tell: the system cannot be fixed; it must be razed.

Let’s start with an obvious question: Why is Trump missing in action in the ideological debate? His critics reflexively chalk every chink in his armor up to personal traits—vanity, impulsiveness, thin skin. But in this case the danger is far more structural than characterological.

Still, if some characterological factors do help to explain Trump’s absence, perhaps three are worthy of note. First, Trump is instinctual, not intellectual. His grand speeches often feel as though they were written by someone else and never quite capture what he truly believes. Creating a lasting movement requires articulating ideological principles that can live on after the founder leaves the scene, but Trump focuses more on branding and marketing than ideological coherence.

Second, he prizes loyalty to a fault. In his search for a loyal team, he has surrounded himself with enforcers like Sergio Gor: a cherubic, 39-year-old libertarian who once served as Rand Paul’s communications director and who was confirmed in October as the new United States ambassador to India. During the first nine months of the second term, Gor ran the Presidential Personnel Office, the crucial gatekeeping operation that placed thousands of political appointees across the government. Gor himself had long moved in the orbit of the Koch network—the sprawling libertarian donor consortium built by the billionaire industrialist Charles Koch and his late brother David, which for decades has funded everything from deregulation think tanks to an uncompromisingly restraint-oriented foreign policy that treats most American military commitments abroad with deep suspicion—especially the commitment to Israel.

That same network had spent years opposing Trump himself, bankrolling his primary rivals and denouncing his tariffs and immigration restrictions. Trump issued a blunt directive upon his return to power: no one affiliated with the Kochs was to be hired. Yet Koch-aligned officials—many of them Gor’s former colleagues or ideological fellow-travelers—quietly took up desks at the Pentagon and State Department. They did not sneak in; the network had simply rebranded its old non-interventionist gospel as the most authentic expression of anti-neocon, anti-deep-state revenge.

Scarred by the traditional foreign-policy establishment of both parties that he believes stabbed him in the back during his first term, Trump overlooked the Koch résumés, recognizing instead the shared enemies. The Koch Libertarians resented the foreign policy establishment as much as he did. To him they were just more knives aimed at the people who had betrayed him. Consequently, only a few people around Trump are actually in full support of his ideological vision. He lacks a reliable team committed to the longer, lonelier task of patrolling the ideological boundaries of the movement he built.

Third, his approach to politics is transactional and personal. He makes deals with individual people, grounded in an understanding of shared interests. Trump himself is the only one who can define what “America First” means, and he likes it that way. Adherence to rigid doctrines obstructs deal-making. When crisis hits, he reaches for the phone. He looks for a fixer, a broker, a loyalist who can cut a deal and smooth the rough edges. But an ideological challenge cannot be solved that way. There is no single person he can call who shares his long-term interest in keeping his coalition intact.

The full dimensions of the challenge become clearest when framed through the question Trump always asks in a crisis: Who do I call? Consider three figures whose responses now shape the future of his movement—Elon Musk, Tucker Carlson, and JD Vance. Each exposes a different structural weakness inside Trump’s coalition. Taken together, they explain why the coalition Trump built is fraying—and why his absence from the debate is less a matter of personality than a sign of deeper trouble ahead.

When Trump asks, “Who do I call?” the first answer is obvious: not Rupert Murdoch. The line is dead—killed the moment Trump hit News Corp with a $10 billion defamation suit in 2025. Even if Murdoch answered, the call would be pointless. The old kingmaker of American conservatism now presides over a shrinking archipelago—Fox, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Post—that the New Right treats like a distant province. But America Firsters live inside a sealed media world of their own: podcasts, YouTube and Rumble feeds, Telegram channels, Gab, and above all X, where attitudes harden long before they ever surface on Fox Primetime. Trump still takes his movement’s temperature by watching Hannity and Ingraham. But the real fights over the future of MAGA are happening in digital spaces that neither he nor Murdoch command.

This is the world Elon Musk now shapes. Trump spent five years trying to construct a counter-media empire: he launched Truth Social (which plateaued at under 10 million monthly actives), turned One America News Network and Newsmax into semi-official house organs, handed press credentials to RSBN and Gateway Pundit, and elevated a rotating cast of loyal amplifiers—Bannon from the War Room, Dan Bongino in his radio heyday, Charlie Kirk before the assassination, even Candace Owens until she broke with him. He urged the base to migrate, floated the possibility of a “Trump TV” network that never materialized, and watched most of his followers drift right back to the big platforms. Nothing cohered. The person who finally built a real, scalable information infrastructure for populism was not Trump but Musk. By transforming X into the central nervous system of the movement—and propelling its loudest voices to unprecedented prominence—Musk succeeded where Trump’s own efforts had stalled.

Musk’s role in Trump’s orbit began as early as November 2022, when he reinstated Trump’s suspended account and then, starting that December, released the Twitter Files—internal documents exposing how the old regime had suppressed conservative voices at the behest of government agencies. That sequence set the stage for the 2024 campaign, where Musk functioned as Trump’s digital field marshal. He poured more than $277 million into swing-state ads and turnout operations through America PAC and, according to multiple independent studies, the platform’s algorithm began delivering dramatically higher visibility to pro-Trump and right-wing accounts after Musk’s public endorsement of Trump in July 2024.

But the intersection of Musk’s interests with Trump’s did not last long. The break that matters most is not over tax rates or H-1B visas. It is over China. Trump’s second-term strategy rests on a single organizing principle: the United States must reorient its alliances, industrial capacity, and military posture to contain a rising China before Beijing overtakes it. Everything he is doing—tariffs, critical-mineral partnerships in Africa and Central Asia, equity stakes in chips and rare-earth supply chains—is designed to make that containment credible abroad and sustainable at home.

Musk is moving in the opposite direction. He has spent a decade cultivating a public posture of admiration toward Beijing. He praises its infrastructure as “100 times faster” than America’s, has called himself “pro-China” on stage in Shanghai, gushes over Chinese “positive energy,” and in late 2022 echoed the CCP line by suggesting Taiwan should become a “special administrative region.”

When Trump reinstated sweeping tariffs in 2025, Musk launched a public war on Peter Navarro—the hard-line trade advisor and chief architect of the new tariff regime—calling him a “moron” and warning that broad decoupling would trigger recession. According to multiple reports, Musk and Tesla opposed Trump’s tariffs. Tesla’s Shanghai gigafactory still produces nearly half the company’s global output and an even larger share of the low-cost batteries that keep the company profitable. Musk’s robotics ambitions—Optimus and the broader humanoid push—depend on Chinese supply chains and manufacturing scale no other country can match on his timetable.

The contradiction is structural. Trump’s MAGA is a nationalist restoration, aimed at reversing the offshoring that hollowed out the middle class and supercharged a hostile competitor. Musk’s world is post-national and accelerationist: Mars colonies, brain–machine interfaces, Artificial General Intelligence. The fastest route to that future runs through frictionless global capital flows, open supply chains, and easy access to the world’s largest single market—China. Trump wants to sever the economic dependence on Beijing. Musk wants to secure his companies inside it. One man is trying to rebuild the American heartland; the other is trying to escape the nation-state entirely.

X is where the divergence becomes dangerous. The platform feeds on engagement—outrage, speed, spectacle. It rewards whatever travels farthest, not whatever stabilizes Trump’s coalition. Since the October 27 Carlson–Fuentes interview exploded across Rumble and flooded onto X, posts branding Trump a “Zionist puppet” or recasting Ukraine aid as “globalist war funding” have racked up millions of impressions, often outpacing sober defenses of Trump’s big-tent project. Holocaust-denying memes outrun statements by government officials.

“Carlson’s fury at the American establishment runs deeper than the fury of the Jan. 6 demonstrators”

Musk’s new location-tagging features have already exposed a swath of “America First” accounts as foreign operators—Pakistanis, Indians, Nigerians—posing as domestic populists. It was a brief reminder that a trend line on X is not the voice of the American electorate. But the platform still remains wide open to manipulation. And whether Musk likes it or not, the same engagement incentives that once pushed Trump’s message to the top now amplify the voices that cast any confrontation with China as a “globalist” trap. Curbing those currents would spark user flight and crater subscriptions.

That leaves a structural tension Musk cannot resolve and Trump cannot ignore: Trump needs a coherent, broad-based coalition to sustain a China strategy; Musk needs maximal engagement to sustain X’s valuation. The vectors run against each other. The result is a platform indispensable to Trump’s movement but increasingly powered by forces working against his strategic aims.

Trump can call Elon—the line still works. But on the central strategic problem of his presidency, their vectors run in opposite directions: Trump toward a fortified nationalism capable of sustaining confrontation with Beijing; Musk toward a globalized tech frontier that requires ongoing access to it. X, the town square of the New Right, has become the amplifier of insurgent voices—some foreign, many disaffected—that are eroding the multi-faith coalition Trump needs to confront China. The man who handed Trump the digital battlefield in 2024 has built an arena whose logic now pulls in the opposite direction—not toward Beijing’s victory, but toward the slow unraveling of the only domestic coalition capable of preventing it.

Trump’s populism has prompted endless comparisons to that of Andrew Jackson—and not without reason. But Jackson could not have won his war on the Bank of the United States without The Globe, edited by Francis Preston Blair—a press sword in the president’s hand. Blair lived one minute’s walk from the White House. The government eventually purchased his home and absorbed it into what is now Blair House, the official presidential guest residence. Jackson understood that reforming the country requires a media lieutenant who will bleed for the cause.

For Trump, the closest approximation to Blair was Tucker Carlson. In 2014–2015, Carlson was a libertarian contrarian—mocking political correctness, indulging in culture-war irritations, questioning foreign adventurism—yet still coloring inside the lines of movement conservatism. The trumpet of Trumpism had not yet sounded. When it did, Carlson was among the first to sense the opportunity. He shed the libertarian skin, dropped the wonk talk, and began preaching nightly about a ruling class that despised its own citizens and was importing a replacement population.

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Trump heard what he took to be loyalty and reciprocated. He called Carlson to praise segments. Carlson asked for nothing in return; he simply amplified Trump louder and cleaner than anyone else. From the Mueller probe through the impeachments, through COVID and the electoral battles of 2020, Carlson cast every assault on Trump as proof that the ruling elite would never forgive Trump’s surprise victory in 2016. Even January 6 he framed as the righteous frustration of the forgotten.

Carlson’s firing from Fox liberated him. Freed from Rupert Murdoch’s constraints, he moved to X and built a media machine that collapsed the distance between broadcaster and audience. The August 2023 interview with Trump—timed to kneecap the GOP primary debate—looked like the consummation of their symbiosis.

But behind the facade of loyalty lurked something much colder. In private text messages later made public in the Dominion Voting Systems defamation case against Fox News, Carlson called Trump “a demonic force, a destroyer” and admitted, “I hate him passionately.” If Trump believed he had finally found his Blair, he was mistaken. In January 2021, as the first Trump era was collapsing, Carlson texted a producer: “We are very, very close to being able to ignore Trump most nights. I truly can’t wait.” Tucker had been harvesting Trump’s audience, not fortifying him.

But for what purpose?

Much has been made of the MAGA generation as a generation without fathers. But Carlson’s story begins with an absent mother. She abandoned Tucker, his father, and his younger brother when he was still a child. By the time his father married Patricia Swanson in 1979, 10-year-old Tucker was already accustomed to privilege—La Jolla, private schools, the early signals of elite upbringing. But marriage into the Swanson family elevated him to a different plane entirely. He entered a world of even greater privilege: legacy wealth, and family trusts. Yet that ascent carried its own shadow. He joined a patrician clan warmed by the afterglow of lost power.

This is the key to his political psychology: Carlson was adopted into an aristocratic line in decline, a family that retains the names, memories, and manners of a ruling class that no longer rules. Tucker Swanson McNear Carlson and his brother, Buckley Swanson Peck Carlson, were raised on the remains of someone else’s fortune—the Swanson frozen-food empire, sold long before either brother was born. “I’ve lived in this world [of affluence] my whole life,” Carlson told a Swiss interviewer in 2018. “I’ve always lived around the ruling class.”

Around them, yes—but not fully of them. Carlson saw enough of elite life to absorb its codes, but enough of its decline to resent its successors. Abandoned by his mother, he was always an outsider. He attended a Swiss boarding school but was expelled; he straightened out later, but his early bowtie persona was a kind of costume, announcing his insider-outsider status.

His fury at the American establishment runs deeper than the fury of the January 6 demonstrators, but unlike theirs it comes from wounds that have no name. When Trump appeared on the scene, Carlson saw in him the tangerine wrecking ball of his dream, the instrument of destruction that he had always dreamed of directing at the American elite.

Carlson harbors nostalgia for an era that vanished decades before he was born. He longs for the old Protestant elite that governed with the surety of inherited authority. “I’m not against an aristocratic system,” he told the Swiss interviewer, but today’s ruling class “doesn’t have the self-awareness you need to be wise.” Nor does Trump’s populism appeal to him. “Populism is what you get when your leaders fail,” he said. When that happens, “the population says this is terrible and they elect someone like Trump.” That nostalgia ensures he cannot support any foreign-policy framework that depends on the very postwar institutions he despises.

This framing reveals the heart of Carlson’s contempt. Trump is, to him, evidence of elite failure—not the solution to it. Trump’s role, Carlson explained in a 2018 interview, was merely to “begin the conversation about what actually matters,” to force the country to ask “obvious questions that no one could answer.” Trump, in Carlson’s mind, is the necessary disrupter not the builder. Trump’s job is to shake the tree; someone else will gather the fruit. That someone, of course, is Carlson himself.

In his interview with Fuentes, Carlson finally made his underlying project explicit. He placed himself among a small cadre of Americans “sincere in their opposition” to neoconservative foreign policy, the only group “able to change the country’s orientation.” For Carlson, the words “neoconservative” and “supportive of Israel” are synonymous. His core mission boils down to a single goal: to break the tie between the United States and the Jewish State.

This project draws not on Trump’s mid-century civic nationalism but on the worldview of the WASP establishment of yesteryear—the America of restricted immigration, minimal foreign commitments, and a culturally homogeneous elite rooted in Protestant Christianity. In Trump’s mid-century vision, Israel fits naturally: a stable ally, a partner against shared enemies, a pillar of evangelical identity. In Carlson’s older, pre-war vision, Israel not only does not belong: it is the very catalyst that corrupted the American elite, diluted its identity, and entangled the nation in global commitments that serve the interests of others.

Since leaving Fox in April 2023, Carlson has built an extraordinarily powerful independent media apparatus, grounded in his ring of aligned podcasts. He now uses that reach to drive a single master narrative: the postwar liberal international order is corrupt, globalist, interventionist, and debt-financed. An Empire displaced the old Republic—and it is run by the Jews.

But Carlson’s deepest hatred is not for the Jews themselves but the Christians who empower them. In his interview with Fuentes, he said flatly, “I despise Christian Zionists more than anyone else on earth.” Unusual in its candor, this line reveals the core of Carlson’s project: breaking the alliance between evangelicals and Israel. He chooses guests who will deliver his message plainly:

• Nick Fuentes, the antisemitic Groyper who denies the Holocaust and praises Hitler.

• Darryl Cooper, who casts Jewish financiers as puppeteers of Churchill.

• Candace Owens, who insists Israel had foreknowledge of 9/11.

• Mother Agapia Stephanopoulos, who claims Israel plans to blow up the Al-Aqsa Mosque.

• Libertarians who describe Israel as the orchestrator of America’s role in the Iraq War.

• Protestant pastors and a country music star who denounce premillennial dispensationalism as a Jewish psy-op.

Their backgrounds differ wildly. Their grievances are eclectic. But one theme unites them: the post-1945 order is corrupt, and the U.S.–Israel alliance is the ultimate source of the corruption. On that basis, Carlson is assembling a shadow coalition: diverse in origin, stirred by Trump’s revolt against the liberal order, yet alienated by the very elements that made Trump’s big tent politically viable—evangelical Zionism, civic pluralism, and multi-faith nationalism.

What Trump built was a grand coalition capable of sustaining the national renewal he envisions. Carlson’s movement seeks to dismantle that foundation from the inside out. Its racism alienates every minority group Trump peeled away from the Left; its antisemitism is fatal, instantly destroying trust with evangelicals—the coalition’s most loyal bloc—whose attachment to Israel is theological, emotional, and non-negotiable. The insurgents claim to be purifying Trumpism; in reality, they are stripping it down to its most self-defeating elements.

“A racist, antisemitic, misogynistic admirer of Hitler and Stalin, Nick Fuentes should be untouchable in any serious political movement—yet within the Gen Z new right he is a totem of defiance”

And that grand domestic coalition came with a new foreign-policy imperative. Since the end of the Cold War, American strategists focused on exporting a liberal orthodoxy—market universalism, democracy promotion, humanitarian intervention. To be sure, neoconservatives and progressives waged their intramural battles, but they shared a core assumption: that American power existed to make the world safe for an ideological project, which in turn helped to underwrite American prosperity.

That consensus broke in 2016. Trump reoriented American foreign policy away from liberal evangelism and toward great-power competition—above all, the contest with China and the network of states orbiting it: Russia, Iran, and North Korea. His aim was not to dismantle the post-1945 system but to repurpose it for a world in which Beijing, not Baghdad or Kabul, was the central threat. Europe mattered again as the industrial flank against Russia; the Indo-Pacific mattered because the first island chain constrains China’s rise; and the Middle East mattered as the center of gravity of the global energy market, which was threatened by China’s partner, Iran.

Israel sits at the center of this architecture. It is America’s most loyal and capable ally in the Middle East, the only one with the military, technological, and intelligence advantages needed and ready to contain Iran, which is the regional linchpin of China’s Eurasian strategy. If the United States wants to keep China boxed in across multiple theaters, Israel is indispensable.

Which is why the domestic antisemitism rising inside the New Right is so strategically destructive. It weakens the domestic coalition precisely where Trump’s strength lies—in the bond between evangelicals, Jews, and traditionalists—and simultaneously blows a hole in the global alliance by undermining the essential military-strategic partnership with Israel in the Middle East. If the United States loses the Trump coalition at home and its key force multiplier in the Middle East, then China is the inevitable strategic winner.

And this is the strangest part: after everything we now know about China—its crash military buildup, its nuclear breakout, its penetration of American universities, tech firms, and intelligence networks—Carlson’s outrage is not directed at Beijing. It is directed at Jerusalem. His conspiracy-obsessed guests see Israeli subversion of the United States everywhere: prior knowledge of 9/11, orchestration of the Iraq War, manipulation of U.S. intelligence, efforts to drag America into a war with Iran. In a world where China is openly working to topple the United States from its position of global leadership, Carlson has built a media universe in which the only foreign power worthy of sustained suspicion is America’s most reliable and capable ally in the Middle East.

Opposition to Trump’s renewal project is grounded in a worldview that sees the business of alliance-building and exercising power as inherently futile. Instead, it rejects the entire post-1945 American security architecture as a failed enterprise. It sees alliances not as tools to be refitted for a new purpose but as corrupt relics that entangle America in other people’s quarrels. It treats the U.S. presence abroad as the cause of domestic decay, not the shield against foreign predators. If that vision were to prevail, the United States would not reform its alliances for the China challenge; it would abandon them. The result would be predictable: crumbling alliances overseas, fractured cohesion at home, and an America too divided to contend with the only rival capable of displacing it.

America First, as defined by Tucker Carlson, struts onstage as a triumphant ideology, too wised-up to succumb to the blandishments of foreign scam artists who would put the lives and wallets of Americans at risk in order to preserve their own graft. In reality, Carlson’s version of America First is a suicide pact, in which the U.S. unilaterally dismantles its own vast and uniquely powerful global military and economic empire in exchange for far lower living standards and a world whose strategic choke-points are controlled by the Chinese Communist Party and its allies. Perhaps the only Americans who would not suffer greatly under such a revisionist regime are the globalist tech billionaires and bankers who Carlson sometimes claims to oppose—who can all shift their operations offshore.

AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File

And yet, though the president knows Carlson is trying to steer MAGA down a new and potentially very dangerous path, he refuses to rein him in. “We did an interview with him—we were at 300 million hits,” Trump said. While the figure is inflated, the logic is real. As long as Carlson delivers enormous audiences, Trump imagines he has no incentive to challenge him. “He said good things about me,” Trump shrugged. “I think he’s good.”

In other words, Trump still treats Carlson the way he treats every powerful interviewer: as a microphone, not a rival political actor. He has always walked into hostile venues—60 Minutes, CNN, The View—because the size of the audience outweighed the risk of the host. Anderson Cooper or Maggie Haberman may occasionally imagine that they are talking directly to Trump’s flock, but Trump has always assumed that his followers would take his side over theirs. He’s the sun at the center of the MAGA universe. The press is a foil for his act. Carlson’s attempt to behave like a political principal doesn’t register for him.

But Carlson is quite clearly catechizing his own coalition—and doing so methodically, week after week, on media that Trump rarely sees. Carlson’s target audience is the cohort shaped by Joe Rogan’s anti-institutional skepticism, Andrew Tate’s performative misogyny, and Nick Fuentes’s open contempt for the most basic of civic norms. Carlson is positioning this formation not as an adjunct to MAGA but as its successor: America First.

Politically, it is far too early to call Donald Trump a lame duck. But on the ideological battlefield, the succession struggle has already begun. Here Carlson clearly believes he holds two structural advantages over Trump—the first being his growing foothold inside Turning Point USA, the largest and most influential youth organization in the MAGA universe. Built by Charlie Kirk into a campus-to-rally pipeline for pro-Trump activism, TPUSA became the institutional bridge between Trump’s coalition and the Gen Z right. Its size, fundraising power, and cultural reach make it the natural staging ground for any post-Trump realignment.

Charlie Kirk’s murder in September threw Turning Point into chaos and removed the one figure who—however imperfectly—kept the organization tethered to Trump’s big-tent, pro-Israel coalition. Kirk himself was personally and consistently Zionist: he traveled to Israel regularly, praised Netanyahu, and refused to let TPUSA drift into open anti-Israel isolationism.

But the movement he built was far more heterogeneous. In the name of free and open debate, Kirk routinely welcomed libertarians, paleoconservatives, and Christian-nationalist voices who rejected Israel and echoed Carlson’s broader critique of American foreign policy. Carlson, in particular, was not a fringe presence but a featured guest—one of the biggest draws at TPUSA events. Kirk acted as a brake on the organization’s anti-Zionist drift even as he gave its leading critics of Israel a prominent stage. His death removed an indispensable internal counterweight capable of restraining that drift, leaving TPUSA suddenly exposed—and uniquely vulnerable to Carlson’s bid for influence.

In the months before and after the assassination, pro-Israel board members and major donors repeatedly urged Kirk—and then his successors—to bar Carlson personally, and to sever ties with the wider anti-Zionist coalition he was assembling. The new leadership, under Charlie’s widow, Erika Kirk, declined to draw that line—even as Kirk herself became the target of vitriolic and defamatory attacks by Carlson associates like Candace Owens. In the heated environment that prevailed, it was easy to see how those attacks might be interpreted as threats to Kirk’s safety, and to the safety of her associates.

The unresolved fight over where to place the boundary of acceptable MAGA discourse quickly spilled beyond Turning Point, erupting at the Heritage Foundation in the explosive controversy over Kevin Roberts’s defense of Carlson. What began as an internal Turning Point succession struggle had become the defining fault line of the post-Trump right. In turn, the drift away from pro-Israel orthodoxy within organizations like Heritage and Turning Point threatens the very coalition Trump needs to sustain a China strategy beyond his presidency.

But Carlson has a second, and perhaps even more important, advantage in his personal relationship to the man who should be Trump’s strongest firewall: Vice President JD Vance.

When Donald Trump asks, “Who do I call?” about ensuring his ideological legacy, the obvious number should be the one belonging to his nominal No. 2 and successor. That call, however, is just as problematic as the one to Musk.

In his interview of Nick Fuentes, Carlson described himself as part of a small cadre “sincere in their opposition” to neoconservative foreign policy and “able to change the country’s orientation.” He then named JD Vance as a member of that cadre—alongside Marjorie Taylor Greene and Matt Gaetz. By placing the sitting vice president on a short list with three of the most outspoken critics of Trump’s foreign policy, Carlson was outing Vance as a co-architect of the very project now threatening to split Trump’s coalition.

Does Vance legitimately belong on this list? The answer is both no and, in the end more weightily, yes.

Start with the no. On Israel, Vance and Trump appear to be in lockstep. Like Trump, Vance understands Israel as a strategic partner against shared adversaries. Senior Israeli officials have told me personally that Vance, behind closed doors, is a “staunch and unambiguous supporter” and a “reliable friend.” Nothing they see in private, they say, resembles the figure Carlson described to Fuentes.

Now the yes. On Ukraine, Vance has placed himself at the tip of the spear against continued U.S. aid, castigating establishment Republicans for writing blank checks to Kyiv while humiliating the Ukrainian President Zelenskyy during his visit to the White House. Vance’s sustained and vocal support for a negotiated settlement—one that would require Ukraine to surrender significant amounts of territory that Russia has thus far failed to seize militarily—has infuriated European allies and hawkish senators. But among many MAGA voters, Vance’s stance reads as a direct indictment of the expeditionary reflex they believe defined post-9/11 Republican foreign policy. It is precisely Vance’s break from “neoconservatism” that Carlson highlights as the entry point for reorienting the right.

“Vice President JD Vance and second lady Usha Vance in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. To those unfamiliar with the anti-Zionist undercurrents of the new right, their visit may have seemed a simple expression of Catholic devotion.”

But Vance edges closer still to Carlson, beginning with the company he keeps. It was Vance who invited Carlson to the Vice President’s official office to co-host Kirk’s weekly podcast after the TPUSA founder’s death, not vice versa. Vance used his stature to rescue the talk show host from a moment of public revulsion from extremist content. With White House backing, Carlson positioned himself as Kirk’s successor as MAGA’s spokesman to and for the young. Vance has publicly explained his willingness to back Carlson as the product of gratitude for helping him to gain the Republican nomination for Vice President. Gratitude and loyalty are no doubt praiseworthy traits, and this explanation is clearly meant in part to underline Vance’s capacity in both areas. Until one considers that the person who granted Vance the nomination was not Tucker Carlson but Donald Trump.

Since converting to Catholicism in 2019, Vance has also clearly absorbed the postliberal critique of the American order articulated by the “Catholic Integralists,” writers like Patrick Deneen and Adrian Vermeule. Their argument—that the liberal founding of the United States carries within it the seeds of its own decay—has become a kind of catechism for alienated young men who believe the system turned against them. Postliberals treat the post-1945 American order as an extension of the liberal founding—both of which were bad. America, in this view, is an ideological empire masquerading as a security system whose corruption was inherent in its founding. Carlson translates that critique directly into geopolitics: alliances are not strategic tools but immoral shackles. American global leadership is a civilizational delusion; support for Israel is the theological distortion that keeps the right from recovering its bearings.

To be sure, Vance does not faithfully repeat all the words of the postliberal prayers, but he kneels at crucial moments. His attacks on Ukraine aid, his call for a negotiated settlement on Russian terms, his insistence that U.S. commitments abroad reflect a spent ideology rather than hard strategy—all place him closer to Carlson’s reframing of American power than to Trump’s attempt to repurpose the postwar system against China.

The result is a worldview that cannot sustain the coalition or the alliance network required to confront Beijing. Every partner becomes an ideological burden, every commitment a mark of corruption.

And here is the deeper point. When Carlson attacks “neoconservatism,” he is not merely engaging in a policy argument.He is deliberately drawing on and mobilizing the older Christian tradition from which post-liberalism draws. For centuries, Catholicism embraced supersessionism—the belief that the Church had displaced Israel in God’s covenant. Vatican II formally rejected this doctrine as false in 1965, but vestiges of the Church’s discarded worldview still circulate in postliberal circles and in parts of the Christian-nationalist right. Carlson has made those remnants operational. He platforms Orthodox figures who recycle medieval anti-Jewish polemics alongside Protestant pastors who denounce Christian Zionism as a theological mistake. In the Fuentes interview he dropped his “just-asking-questions” posture altogether and called Christian Zionism “a heresy.”

Strip away the theological robes, and the geopolitical effect is alarming: a right that recoils from the very alliances Trump needs to anchor a China strategy across the Middle East and Indo-Pacific. This is the intellectual milieu in which Vance is openly operating. And that is why Carlson folded him into a cadre “able to change the country’s orientation.”

Seen from inside the New Right, Vance’s September decision to guest-host Kirk’s podcast—and to feature Carlson as his guest less than a week after the assassination—read as an unmistakable signal of alignment. Not an endorsement of antisemitism per se, but a willingness to treat Carlson’s antisemitic ecosystem as an acceptable part of the coalition. More than that: it conferred legitimacy on a current of thought whose logical terminus is the dismantling of the evangelical-Zionist pillar on which Trump’s big-tent coalition depends. In elevating Carlson at precisely the moment TPUSA had lost its internal ballast, Vance strengthened Carlson’s claim to ideological succession and accelerated the drift toward a right that cannot sustain America’s partnership with Israel—or the China strategy that partnership makes possible.

Vance’s courtship of Tucker Carlson marks a sharp departure from the tradition that brought Trump to power—not the religio-political doctrine of this or that postliberal Catholic theorist, but the Eisenhower–Reagan model of religious politics in America.

Eisenhower in particular has much to teach Vance. He famously said, “Our government makes no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.” Clumsy and easily mocked, the statement remains strategically astute. Eisenhower understood that in the United States religion is politically potent only when articulated broadly enough to bind rival traditions together.

He practiced what he preached. For his second inauguration he opened the Bible his mother had given him upon his graduation from West Point. The verse before him read: “Blessed is the nation whose God is Jehovah.” The word “Jehovah” would have revealed the Bible as a Watchtower edition—published by the Jehovah’s Witnesses, then one of America’s most stigmatized sects. Eisenhower simply read the verse aloud as “the Lord.” Ten days after his first inauguration, he quietly converted to Presbyterianism—the faith of the American elite. His pastor, Edward Elson, baptized him in the National Presbyterian Church. The timing—barely a week after taking office—suggests political prudence more than theological urgency.

Nathan Howard/Pool Photo via AP

Eisenhower also cultivated both halves of mid-century Protestantism—the mainline and the evangelicals—even though their theological disagreements ran as deep as the social divisions they often reflected. His pastor in Washington was Edward Elson, but he made a point of bringing Billy Graham into the White House, seeking Graham’s counsel and hosting him repeatedly. Eisenhower rode these two horses simultaneously because he understood that, properly harnessed, religion could foster national cohesion rather than sectarian fracture.

Only one other modern Republican president matched that level of intuitive mastery: Ronald Reagan. His career-long approval rating of 53% comes closest to Eisenhower’s and rivaled any Democrat in the polling era. Reagan, too, treated religion not as dogma but as a moral vernacular—a language capable of uniting evangelicals, Catholics, Jews, and even secular patriots around a shared civic covenant. By offering America as the “city upon a hill,” he elevated belief itself, not any particular doctrinal claim. He transformed religion from a source of fracture into the grammar of national renewal.

Trump instinctively continued that Eisenhower–Reagan tradition. His coalition works because it is broad—evangelicals alongside Catholics, observant Jews alongside secular conservatives, Black Pentecostals alongside Hispanic charismatics. Despite his irreligious background, he understands what Eisenhower understood: that the language of American faith must be expansive and sunny if it is to be politically useful.

Vance is moving in the opposite direction. He is narrowing the vocabulary of American civic religion at the very moment it must remain wide. Where Eisenhower blurred sectarian lines, Vance sharpens them. Where Reagan invited competing traditions into a single civic myth, Vance draws distinctions. Where Trump kept the tent open, Vance signals a future in which the tent narrows.

An example of Vance’s penchant for playing up sectarian divisions rather than working to forge a winning electoral coalition came with his recent visit to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Accompanied by Second Lady Usha Vance and a host of photographers, he met with the Latin Patriarch, received confession, and participated in a private Franciscan Mass inside the Edicule. He knelt at the Stone of Anointing, prayed at the Chapel of the Crucifixion, lit candles from the tomb’s eternal flame, and posted afterward: “What an amazing blessing to have visited the site of Christ’s death and resurrection.”

To those unfamiliar with the anti-Zionist undercurrents of the New Right, the episode might well have appeared as a simple expression of Catholic devotion, which Vance’s online messaging apparatus made a point of rebranding as “Christian.” Lauren Witzke—a “Christian nationalist” former Delaware Senate candidate now aligned with Fuentes—circulated the clip with the caption: “The Vice President of the United States JD Vance opted out of the wall-kissing ritual in Israel, instead choosing to visit the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.” This framing was enthusiastically adopted by other self-styled Christian nationalist influencers like Steve Bannon, who celebrated the need for “a Christian state of Jerusalem.”

Evangelicals, who form the backbone of Trump’s pro-Israel coalition, were pleased by none of this. Protestants contest the historical location of the crucifixion, with some favoring the Garden Tomb and others rejecting both sites as unproven.

The denigration of Israeli national symbols like the Western Wall entirely misreads how evangelicals—and many Catholics—understand the place. Evangelicals do not see a visit to the Wall as an act of submission to Jews. Jesus taught in the Temple; the Gospels and archaeology both attest to the site, and for evangelical theology the covenant with Israel and the covenant fulfilled in Christ are not competing dispensations but a single unfolding promise. To pray at the Wall is, in their view, to stand where Jesus stood and to honor the continuity of God’s dealings with His people.

And Vance, as a Catholic, had no need to play to sectarian sentiments. There is an unimpeachable Catholic precedent: John Paul II’s 2000 pilgrimage, during which he placed a handwritten prayer in the Wall’s stones—“God of our fathers… we wish to commit ourselves to genuine brotherhood with the people of the Covenant.” When Vance’s allies mocked “kissing the wall” as a humiliation ritual imposed by Jewish donors, evangelicals and many Catholics saw not bravado but a gratuitous rupture with a shared sacred history. In the Vance–Carlson alignment, they recognized an effort to redefine that history—and to sever the covenantal bond that has long anchored the pro-Israel core of the conservative coalition.

This recognition triggered discontent among evangelicals, which erupted into open confrontation. On Dec. 2, 2025, prominent Christian Zionist Dr. Michael D. Evans—founder of the Friends of Zion Museum—told a Jerusalem Post reporter: “Right now we are having a movement within the MAGA movement that is anti-Israel. It is very serious because it is led by Tucker Carlson, who is very close to the vice president. He is coming out and saying worse things presently than the Nazi Party said at their platform in 1920.” Days later, at a gala event attended by PM Netanyahu and Sarah, his wife, Evans pledged to train 100,000 Christian ambassadors to combat antisemitism and defend Israel, signaling the deepening rift inside Trump’s grand domestic coalition.

Vance’s political use of his own religious journey is therefore clever, but brittle. The intellectual circle that appears to shape his worldview—Deneen and Vermeule, the Catholic integralists—has major influence online, but almost none in electoral politics or within the Republican Party. Catholics as a voting bloc are smaller than evangelicals. Whereas evangelicals overwhelmingly vote Republican, Catholics, traditionally, have been split nearly evenly between the parties, and in recent decades have been far less churchgoing. Furthermore, most American Catholics are not integralists; they are not seeking to impose a premodern moral architecture on a pluralistic, democratic society. If all the true Catholic integralists in the United States gathered for an annual conference, they could fill a mid-sized bistro in Lower Manhattan.

That wager—that Vance can maintain operational loyalty to Israel while gesturing toward a post-evangelical Republican future shaped by Tucker Carlson—puts at risk the most indispensable component of the MAGA coalition: evangelicals. Their support is structural, not ornamental. Trump’s original political breakthrough—uniting evangelicals, Orthodox Jews, traditionalist Catholics, married women, and portions of Black and Hispanic churchgoers in a governing majority—cannot survive any project that treats evangelical Zionism as expendable. The reason why is simple math: Subtract evangelicals (and Orthodox Jews) and the Trump majority becomes a minority.

The strength of MAGA was never doctrinal purity. It was breadth—a unity of people who could never come together around a shared theology but could agree that the Progressive elite was assaulting their fundamental beliefs and their place in American life. That coalition survives only if its political vocabulary remains wide enough to include them. When the coalition fractures, so does the political foundation for a China strategy that can endure after Trump leaves the stage.

The United States will not lose the 21st century to Beijing on some distant battlefield. It will lose it here at home—in X posts and podcast studios—while the grand American majority assembled to prevent that outcome tears itself apart debating whether the Jews orchestrated 9/11.

Michael Doran is Director of the Center for Peace and Security in the Middle East and a Senior Fellow at the Hudson Institute in Washington, D.C.

[

#Donald Trump

](https://archive.is/o/7bOzT/https://www.tabletmag.com/tags/donald-trump)[

#JD Vance

](https://archive.is/o/7bOzT/https://www.tabletmag.com/tags/j-d-vance)[

#Tucker Carlson

](https://archive.is/o/7bOzT/https://www.tabletmag.com/tags/tucker-carlson)[

#MAGA

](https://archive.is/o/7bOzT/https://www.tabletmag.com/tags/maga)