“I was the victim of a grooming gang and now I’m a survivor. I endured hell and everyone did fuck all.” Ellie Reynolds* was gang-raped and abused as a young teenager in the Nineties, in her hometown of Barrow-in-Furness. Only now are we in Preston Crown Court to hear the sentencing of her abusers.

The grooming gang story is often framed as something that happened far away, in the North, in the bad old Nineties and 2000s. But this is a story about what is happening right now.

Ellie’s abuse began in 1996 and carried on for another four years. And as we know now, this wasn’t an isolated incident. The systematic abuse of literally thousands of children was taking place in Rotherham, Bradford, Derbyshire, Huddersfield, Oxford, Rochdale, and Bristol, among others. We only know about this because of brave victims, dogged whistleblowers and the resulting prosecutions. But while many resilient women have come forward, so many others remained silent — ashamed, disbelieved, ignored.

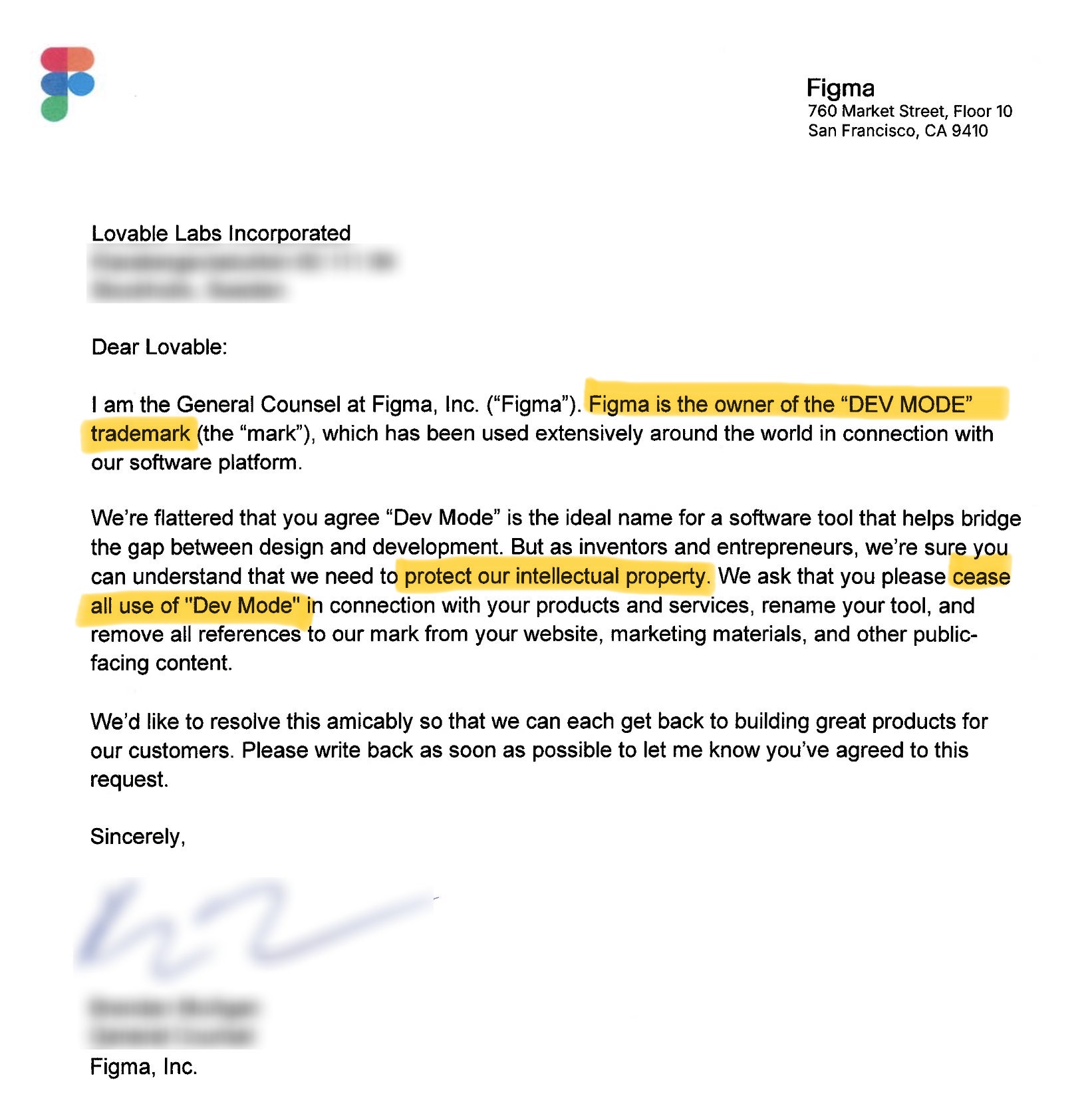

In January, Elon Musk targeted our country’s failings when he posted on X that: “[Keir] Starmer was complicit in the RAPE OF BRITAIN when he was head of Crown Prosecution for six years (2008-2013)”, demanding that he “face charges for his complicity in the worst mass crime in the history of Britain”. It was in response to Jess Phillips’ remarkable decision, as minister for the safeguarding of women, to reject a national public inquiry into the grooming of children in Oldham.

Whatever his motivation, Musk was right in his analysis. This is a scandal that has been swept under the carpet for years. I’ve been following grooming cases for almost my whole career. Over the decades, a succession of inquiries and reports has indicated the nature and scale of the catastrophe, yet nothing has been done to address the underlying problem, let alone fix it.

In 2014, we had the Jay Report and Operation Bullfinch. There have been independent reviews into the failings of Greater Manchester, Bristol and Derby, among other cities. And it has been three years since the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA), which concluded that the current system is fundamentally flawed and incapable of protecting vulnerable children.

Yet despite the money, effort and desperate testimonials poured into each of these investigations, little has changed. The Conservative government was tasked with implementing the 20 recommendations of the final IICSA report. It did nothing, save passing the burden of responsibility on to Labour after last July’s election.

At the start of this year, it looked like something might be done. Home Secretary Yvette Cooper announced a £10 million plan for a series of local inquiries into grooming gangs, as well as a rapid review of the current scale of exploitation across the UK. To lead the review, Cooper appointed Tom Crowther KC, who chaired the inquiry into child sex abuse in Telford. Published in 2022, Crowther found that more than 1,000 girls had been abused in the Shropshire town over a period of 30 years, amid “shocking” failures by the police and local council. Hopes rose that, finally, the Government was taking the problem seriously.

And yet, barely three months in, the wheels are already coming off. Crowther has expressed frustration with the little progress that has been made: the Government isn’t collaborating, the process is being watered down, and the political will simply isn’t there. That matters, and not just historically. Without asking why justice has come so slowly, and without attempting to understand why the grooming happened — and still happens — nothing will change. Communities will continue to be demonised, gangs will continue to operate with impunity, and a steady stream of offenders will continue to be released back into the community, many back into the very areas where their victims still live.

***

Almost 30 years ago, in 1996, I visited a tiny charity in the centre of Leeds. There I met Angela*, a hard-working single mother, who described how she had discovered her daughter Jane*, 14, was being picked up in taxis by Asian men, who then used her for sex.

Her mother was desperate, on the edge of tears. “She stays out late and she’s been seen with older lads in the town centre,” Angela told me. “I’ve given [the] police a load of car number plates and names but they say she’s choosing this lifestyle and there’s nothing they can do.”

Angela and her daughter lived in Keighley, a market town in West Yorkshire small enough for everyone to know your business, and a place infamous as the so-called ground zero of the grooming gangs. It was here, back in 2002, that Ann Cryer, the town’s then Labour MP, first exposed how groups of predominantly Pakistani men were preying on predominantly white girls. And it was in Keighley, a year later, that the first grooming gang conviction was secured.

I had long been aware of organised gangs targeting vulnerable girls. But it was only through meeting mothers of victims that I realised how little the authorities cared about these girls.

Even in those early days, the pattern was clear. The victims were generally vulnerable children from impoverished towns with high unemployment and racial disharmony — and society tended to see them as worthless. Even the police described them as “troublesome” and “slags”. Their families, if they had any, were seen as disreputable. All the while, social workers talked blithely about “personal choice” and “consent”.

There was another factor too: race. Throughout the 2000s, I was one of a handful of civilians invited to attend the annual Police Vice Conference, where experts in child sexual abuse and exploitation shared intelligence. It was at the 2004 conference that I heard, from one of the most senior police officers in attendance, that fears of “race riots” were growing — as more and more information came in about the predominance of Pakistani Muslims in child abuse and pimping gangs across the north of England.

This added another complication to the toxic mix: politics. In the absence of mainstream political support, other political agents would run to “rescue” — or weaponise — victims. This was certainly the case when Charlene Downes went missing from her Blackpool home in November 2003. Blackpool has always been a hotspot for child abuse, and a growing immigrant community back then was the source of much local suspicion.

Early on in their investigation, police became aware that Charlene, then 14, had along with various other girls been targeted by abusers active in the town, swapping sex for food, cigarettes and affection. It was a modus operandi that was becoming familiar to those who were following the escalation of these cases. “I found out,” her mother told me back then, “that Charlene was getting chips for a blow job. How can those bastards do that to kids?”

During the hunt for Charlene, police uncovered Blackpool’s open secret: Muslim men, from Southeast Asia and the Middle East, had latched on to the opportunities afforded them by the nighttime economy. Taxi drivers and takeaway workers would prey on girls, passing them around to each other, inviting friends and business associates to come to the back rooms of kebab shops, and the offices of mini cab firms, to have sex with them. This was organised, a business, run for money, with the perk of on-tap sex with terrified victims.

While it was by no means certain that Charlene was being solely abused by immigrants, far-Right political parties saw an opportunity. The BNP, with the support of Charlene’s family, latched onto her case as an example of the problem caused by Pakistani Muslim men “invading” Britain. Once they got hold of her, the narrative was set.

The pernicious effect of the BNP could be seen months after Charlene’s disappearance. In 2004, Edge of the City, a documentary about gang grooming in Bradford, was due to be released. Abuse cases had been surfacing at an alarming rate, and the filmmaker Anna Hall was the first to expose the pattern we now know as gang grooming. But the BNP gleefully leapt on the film, describing it as “a party political broadcast” for its local election campaign. West Yorkshire Police, fearing a racist backlash, advised Channel 4 to withdraw the film from transmission at the last minute. Community cohesion took precedence over the rape of kids.

It’s something we’re still seeing. Since most of the worst cases we know about involve gangs of Asian, Muslim men pimping out white women, a reluctance to act is supercharged by fears of being accused of racism. In the past, authorities would rather have turned a blind eye. Today, despite everything we know, the same thing is happening. Only last week, Sir Trevor Phillips claimed that the Home Secretary was failing to push ahead with local reviews “because of the demographic of people involved… largely Pakistani Muslim background, and also in Labour-held seats and councils who would be offended by it”.

Meanwhile, back in the early 2000s, Charlene remained missing. I kept an eye on her story, wondering if she’d ever turn up. By 2006, when the evidence of her being horrifically abused by multiple men had been exposed, I pitched the story to my then editor at The Guardian, Katherine Viner. She acted much as the authorities did. She called me and said: “We would be called racist if we publish this.” So I wrote it for The Sunday Times magazine. The day after it was published, I was added to the Islamophobia Watch website.

All the while, the politicisation of the grooming gangs continues. Over the years, EDL poster boy Tommy Robinson has used the issue to further his own political agenda against “radical Islam”. Neither an expert in abuse, nor a particular champion of children or women, he has if anything made things worse for victims. In 2019, Robinson was imprisoned for contempt of court after breaching reporting restrictions on one rape trial and jeopardising due process. Notwithstanding his motivation, he has been trumpeted as a hero by Musk and many others for his propagandising of the issue. In the justice vacuum, bad actors spy an opportunity.

In the end, Charlene’s body was never found. The hunt for her has been one of Lancashire Police’s longest-running missing person inquiries. But, many years after her disappearance, rumours began circulating around Blackpool that her body had been chopped up and used as kebab meat, sold from the very takeaways where she and other girls were abused.

***

Court 1 at Preston Crown Court is the biggest in the building: the press bench is full, and the public gallery is packed with survivors and supporters, including Ellie Reynolds and myself. It is January 2025, and we are here to see the sentencing of three monstrous brothers who raped, sold, abused and tortured a succession of vulnerable young girls between 1996 and 2010. It has been 30 years since these men started committing their crimes.

Amran Miah, 49, Alman Miah, 47, and Shah Joman Miah (known as “Sarj”), 38, were violent predators who targeted girls in abusive family homes or care and foster placements. Some of their victims were as young as seven. The girls were lured in by promises of romance, rides in fast cars, vodka, cigarettes, cannabis and the freedom to hang out at the men’s apartments: they leapt at what they thought was a chance to escape. A life where someone cared. The promises couldn’t have been further from the truth, as they were prostituted from cars, on streets and in apartments across Britain. Often locked in rooms with nothing but a filthy mattress, they were forced into violent sexual acts, sometimes with several men at once.

Refusal to comply would mean being beaten with dog chains, forced to drink their own urine and tortured. One of the Miah victims showed me cigarette burns on her legs, stomach and arms. “[The pimp] used me as an ashtray,” she tells me, “and a few times when I was asleep he’d piss all over me, not bothering to go to the toilet, then make me get up and wash the sheets while he went back to sleep.”

Another girl, who was not in court but followed the proceedings by video link, was abused over a period of five years, from the age of seven. “He ejaculated into her mouth,” the judge tells the court. “She said that when [he] ejaculated she began to cry and make a noise and [he] replied, ‘Stop it or we’ll get found out’.” She was raped, filmed and photographed.

Elizabeth*, another girl, is in court that day too. During the lunch break, she tells me that she knew of at least one of the victims in the trial considering withdrawing their evidence because they were convinced they wouldn’t be believed. Elizabeth was a witness to the grooming gang activities, including seeing girls being taken to the room above a takeaway to be raped, some still in their school uniforms. She was a key witness for the prosecution, but after she reported what she had seen, word soon got around. “They smashed my windows,” she says of the threats she received. “I feel scared despite the police promising I am protected.”

In court, defence barristers make valiant attempts to introduce mitigation: one defendant suffered with depression, another has an autistic child, and each of the brothers has a work ethic and is “loyal” to the others. But the judge reminds the court of their depravity: “You threatened to tell [a witness] that if she said anything to the police you would set her house on fire. She spoke of attending hospital due to anxiety. I am satisfied that each of you acted in a predatory and paedophilic manner… You saw your victims as vehicles to be used and abused at your will and when you wanted to. You treated them with utter contempt.” The robust sentencing reflected the seriousness of the crimes: all three men were sentenced to at least a decade in prison. Facing the stiffest sentence, Shah Joman Miah was sent down for a minimum of 21 years and 232 days.

These children were treated as disposable rubbish by the men who raped and pimped them. But a similarly appalling punishment was meted out by the authorities tasked with protecting them.

***

For years, Sara Rowbotham was a sexual health worker in Rochdale. As the coordinator of the Crisis Intervention Team, a body linked to the NHS, from 2003 to 2014, it was her job to identify young people who were vulnerable to child sex exploitation.

Rowbotham repeatedly tried to alert police and social services, from as early as 2004, to the fact that girls were being systematically abused by gangs of older Asian men. She made over 100 referrals, none of which was actioned. During her time as a sexual health worker, she made something she called the “Boyfriend Book” — in which she kept records of all of the perpetrators, and their details as given by their victims. The book was eventually used in court as evidence. It is still being used today, at the ongoing trials at which she is called as a witness, some 20 years after the abuse first happened.

Rowbotham went on to provide key evidence that ended in the conviction of nine men in 2012, and 10 more in a separate investigation in 2015. “It was my job to keep those girls safe,” she tells me. “I tried to do that, I kept referring cases to police, to social workers, and they did nothing. They ignored me. They turned against me and shut me out.”

This reluctance among authorities to believe the young victims is borne out by research by Sarah Hall, who has been involved in child protection for 20 years. The social workers understood sexually exploited girls as being able to make choices, supposedly unlike girls abused in the home. Hall says she often heard the phrasing “putting themselves in risky situations”.

Because these girls were widely viewed as “sluts”, they were often ignored. “They were all Pakistani, except one who was Algerian,” Fiona tells me, recounting her abuse at the hands of a gang in 2008, back when she was just 13. “But the police denied they existed.” Fiona was in care, and staff knew from very early on what was happening. “They would have multiagency meetings but no one would turn up. They said, ‘Well she goes missing all the time so she must enjoy it’.”

Vulnerable, confused and angry, Fiona could only lash out. “Because I wasn’t getting listened to and my mental health was deteriorating quickly, I ended up getting done for assault on the staff and criminal damage on the care home… So my criminal record is all to do with criminal damage and assault of care home staff and police officers.” Think of it: this girl asked for help to escape her rapists, and ended up with a criminal record herself.

Damningly, the serious case review conducted by the local authority, when it happened, found 18 instances of sexual assault or rape that the care home had failed to report to the police. Fiona has been fighting for “justice and accountability” for the past decade. Amber* was similarly criminalised. Barely 14 when she was first targeted in 2007, she was already on the child protection register in Rochester in Kent. The men lured her in, groomed her and then subjected her to repeated and violent sexual abuse.

That nightmare should have ended with the arrest and trial of the perpetrators. But instead, the police, CPS and even social services treated Amber as a criminal. In 2009, when she was 16, uniformed officers came to her mother’s house, arrested her and took her to the police station.

Because, like all the other girls, Amber had been told she had to bring her friends along to meet some of the gang members, she was portrayed as an assistant pimp. When nine of the men were eventually put on trial for crimes relating to Amber and other girls, she was part of the case — but not as a victim. The prosecutors had put her name on the indictment as one of the offenders.

Though she was neither tried nor convicted, the media described her in court as a “honey monster”. Nor did her ordeal end when the men were sent down. Social services pursued her with a view to removing both her very young child and her unborn second baby. The case dragged on for 18 months before the judge dismissed it. Five years passed before an apology and compensation came from social services. “It’s absolutely outrageous that none of them have still been charged for me, none of them have even been prosecuted,” Amber tells me. “I still can’t get my head around that after all these years.”

Two decades on, Sarah Hall insists little has changed. “There’s still lots of victim blaming,” she tells me, “blaming of parents, stereotyping, and young people are deemed to be making a choice and the systems back that up. Depending on where and by whom you are raped and sexually assaulted in this country as a kid, you will either be safe-guarded or you won’t be.”

***

It is raining in Manchester when I arrive at the Crown Court, where eight Asian men from Rochdale stand accused of treating two girls as “sex slaves”. They are charged with 56 sexual offences, include grooming, sexually exploiting and raping two 13-year olds between 2001 and 2006. It is February 2025.

There are police outside, sent from Rochdale to make sure “there are no security issues, due to the sensitivity of the case”. But the case is 25 years old, I say. “It is old,” replies one of the officers, “but unfortunately it’s still happening today.”

There are eight men in the dock, all Pakistani Muslim, ranging in age from 39 to 66. They are accused of rape and other sexual offences against two girls between 2001 and 2006. Girl A and Girl B, both abused from the age of 13, were in court, surrounded by family and friends. The women are in their 30s now, but wear the look of deep trauma. Giving evidence, Girl A said that she had been abused by at least 100 men, but when she then mentioned the figure of 200, she was challenged by one of the defence barristers, implying she was lying. “There could’ve been more to be fair,” she replied. “There [were] that many it was hard to keep count.”

The abuse began when the girls, in local authority care, started hanging around the market, where Mohammed Zahid, one of the men on trial, had a lingerie stall. Both girls were casual workers on the stall, paid in clothes, cigarettes and alcohol. They were also expected to have degradingly sadistic sex with Zahid (known as “Boss” or the “Knickerman”) and his associates.

Though Girl A told local children’s services about “hanging around” with older men in 2004 — as well as drinking and using drugs, and having sex with men introduced to her by “Boss” — neither her school nor social services made any reports to the police. Instead, one of the girls was labelled a “prostitute” at the age of 10. Rowbotham was ignored when she reported it to police and social services. As she puts it: “I can only imagine how many other girls they went on to harm.”

“One of the girls was labelled a ‘prostitute’ at the age of 10.”

Rowbotham tells me about one of the mothers of Girl A, back in 2005, before police were even acknowledging there was a problem. “Girl A’s mum was out of her mind trying to get the cops to do something — she phoned them constantly and I encouraged her to keep doing it even if they didn’t respond,” she says. “And she was not the only one desperate to get them to act.”

This particular case only came to trial after one of the girls tracked an abuser down on Facebook and spotted a second “selling fruit and veg out of a van near a school”. So many of these men are still prowling the streets. There are dozens known to have been active gang members who have never been arrested, or spent a day in prison. And those hundreds of men who paid to rape the girls remain invisible.

***

The number of abused girls we know about is easily in the tens of thousands. This dwarfs the number of convictions. Between 2005 and 2017, only 264 men were found guilty. Every historic review includes evidence that social services teams and police officers were reluctant to pursue groups of Asian men for fear of being accused of racism. It also seems likely that police feared civil unrest among the white population, not least given the rise of the BNP and the race-baiting of Tommy Robinson. Once again, these fears are surely relevant today too, especially given the disorder last summer.

Yet whatever the grim political logic, this attitude is hard to justify, especially when you consider the words of perpetrators themselves. One example is Shabir Ahmed, the leader of one of the Rochdale grooming gangs, who was convicted in 2013. During his trial, Ahmed made his feelings clear. “We are the supreme race, not these white bastards… You destroyed my community and our children. None of us did that. White people trained those girls to be so much [more] advanced in sex.”

As that statement implies, race is yet again a factor here, something also clear from the statistics. Of the few hundred men convicted between 2005-17, 84% of them were Asian. In the Rochdale abuse scandal of 2012, the men involved were primarily British Pakistani men. In Telford, according to the independent 2022 inquiry there, the abusers were also men of “southern Asian heritage”.

While white men are certainly involved in child exploitation, then, the continued predominance of South Asian men in grooming gangs is undeniable. Data released in January 2025 has found that Pakistanis are up to four times more likely to be involved than the general population. And figures from all 43 forces in England and Wales show that 13.7% of child sexual exploitation in the first nine months of 2024 involved Pakistani men, a rise from under 7% in 2023.

But it’s a mistake to think that these rapists restrict themselves to white victims. Zlakha Ahmed, a survivor of gang abuse in Telford, is testament to this. Now 62, her abuse happened when she was just seven. “It was two men who were close family members,” she tells me. “I was taken to a park one day and I was raped by a gang of men.”

Farida*, for her part, was the victim of a gang of largely Pakistani men operating in Oxfordshire, 21 of whom have since been convicted. Between 2010 and 2020, 18 victims gave evidence in six trials about abuse spanning from the late Nineties to the late 2000s.

Zlakha Ahmed told the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA): “It feels as though BME women and girls are shrugged off by statutory services, which are staffed by predominantly white individuals. When it comes to Asian children in particular, a lot of white workers bury their heads in the sand and then we are blamed as a community for not coming forward.”

It was the same for Farida. When she reported being raped and kidnapped by grooming gang members to police in Oxford, they did not believe her. “Because I am Asian and with a Pakistani name,” she says, “I didn’t fit the stereotype for this officer.”

The stark reality, then, is that police and prosecutors have a dismal record when it comes to dealing with the sexual abuse of girls, whatever the class or ethnicities of the victims and perpetrators. Data from the Centre of Expertise on Child Sexual Abuse shows that during 2023-4, only 12% of reports were subject to any criminal justice intervention, and around two thirds of investigations were closed because of “evidential difficulties”.

***

Kevin Hyland is a former Metropolitan Police Officer, the UK’s first Independent Anti-Slavery Commissioner, and an expert in human trafficking and sexual exploitation. He understands organised gang abuse and how to get the best results during investigations. More than that, he is keen to explore how law enforcement can stop gangs getting access to girls in the first place.

“If entire groups believe they can operate with impunity and start to target young girls but then feel the weight against them, it will deter some from offending,” he says. “That weight should be societal, it should be legal, it should be from their own backgrounds and culture.”

Maggie Oliver makes a similar point. Credited with exposing the Rochdale grooming gang scandal, in 2012 she left Greater Manchester Police in protest at its handling of the town’s grooming trial. She tells me that gangs are still active in Manchester, Telford, Rochdale, Rotherham, Blackpool and Leeds. More to the point, Oliver insists that the grooming gang phenomenon is linked to a belief system of people who don’t share the same values as the British public generally — “that this will just continue to explode unless we get a grip of it as the root cause of this sort of abuse”.

For Hyland, though, pushing the line that any type of crime is committed exclusively or even predominantly by one particular group allows those outside the demographic to hide in plain sight, and for law enforcers and social workers to fail to follow leads. As he says: “One of the big challenges we’ve got is that policing has become so complex, so politically correct, so influenced by outside measures, that the focus on the bigger picture is compromised.”

Not that there seems much appetite to address the problem. Amber, the victim from Rochester, tells me that men arrested in Rochdale are “still there, still delivering takeaways, still driving taxis”. She’s even given some names to police “but [they] don’t go and arrest them. I think it’s too much effort for them.”

All the while, how grooming happens is changing. Smartphones and the internet now mean that men no longer have to sit and wait outside a victim’s home. Instead, they can make initial contact through an online platform, which means less risk of being caught.

As Oliver explains, men will increasingly befriend girls online, pretending to be a younger boy, before coercing the child into sending explicit photographs — which will then be used as blackmail. The targets, anyway, are the same: vulnerable girls who feel as though they’re being treated like grown-ups, even as they’re forced to engage in terrible sexual activity.

Oliver is well aware, through work at her eponymous foundation, that state complacency means grooming gangs are as entrenched as ever. No wonder, then, that this week she’s launching #TheyKnew, a new campaign aiming to bring legal action against officials who failed to act in the face of terrible abuse. Alongside Oliver are two survivors of grooming gang abuse, Elizabeth* and Samantha, both of whom I’ve met, a heartening reminder that some victims are managing to turn round their lives.

Unfortunately, good news is hard to come by, with Robbie Moore, the current Conservative MP for Keighley, worrying that the problem is actually worsening. “[W]hat we’ve unfortunately got here in Bradford is the local authority not willing to trigger that process of having an inquiry,” he says. “But Bradford, from the evidence I have seen, has a far bigger problem even than the likes of Rochdale.”

I know from bitter experience that where crime flourishes, so too does exploitation of women and girls. And child sexual exploitation has followed the growth of county drug lines. One policeman I know in southeast England says he constantly hears how the gangs are now dominated by pimps running girls. “I have taken statements from half a dozen girls, from age 14 to 18, in the past six months who want to bring charges against men who are, effectively, grooming gang leaders. The perpetrators are usually from immigrant groupings, and operate taxis and takeaways, but they also supply some of the drugs to the runners, and keep the girls for themselves to share around and sell to business associates.”

Resources aren’t usually made available to deal with the sexual exploitation element of these crimes, with officers encouraged to focus on drugs and weapons. One senior officer very recently told me that the victims are part of the problem and know exactly what they are doing — it’s the same old harmful narrative being trotted out again.

One recommendation from the 2022 IICSA report is that data should be collected on exploitation networks. Shockingly, it’s yet to happen. Another suggestion is the mandatory reporting of child sexual abuse at school or the GP. Both of these recommendations, if properly implemented, would make a difference. But to date, nothing has happened.

While all the victims would welcome further scrutiny of the scandal, meanwhile, most of all they want to see broad improvements to the criminal justice system. What’s in no doubt is that it’s currently unfit for purpose: neither detecting perpetrators nor keeping victims safe.

Meanwhile, our politicians seem determined to keep looking the other way. Though Cooper announced those new local inquiries at the start of the year, Jess Phillips — allegedly the minister responsible for safeguarding women and girls — is already backtracking. At the start of April, she said there would be a more “flexible approach to support both full independent local inquiries and more bespoke work, including local victims’ panels or locally led audits of the handling of historical cases”. Translation: the £5 million set aside for the inquiries was no longer being allocated. It also meant that politicians, rather than independent agents like Tom Crowther, would drive the investigations.

This announcement was met by horror from many. That includes Trevor Phillips, who described the response as “shameful” because, he said, it was so obviously politically motivated. Robbie Moore, for his part, is “completely infuriated” by the Government’s update, arguing it’s an admission that pretty much no progress has been made. Let’s not forget: these inquiries were supposed to have been launched by Easter. Trevor Philips is right. It’s shameful that Jess Phillips, a self-styled advocate for abused women and girls, appears to have suddenly lost enthusiasm for dealing with one of the biggest child sexual abuse scandals in modern British history — likely for fear of being branded a racist. What hope is there for girls being abused right now, if our politicians still refuse to even admit the problem exists?

***

John’s* daughter Evie* was 14 when she was targeted by a gang of taxi drivers. He is now helping support another 14-year-old girl who remains under the control of some of the same men. Evie reported her abusers to the police, after eight months of rape, sexual assault and degradation. “She was made to strip naked and then dance for the abusers,” John tells me. “And she says money changed hands. They would have sex with her. She was just a kid.”

Sophie*, another girl, one day turned up on John’s doorstep in the northwest of England, having heard that one of Evie’s abusers had been convicted of rape, and realising that the same gang was targeting her.

“I have told the police, repeatedly, that this gang is in operation right now, that that some of the same men that raped my daughter are now doing it to others,” John tells me. But despite going to the police in December last year, he says nothing has happened so far.

Sophie, for her part, is desperate, and has asked for help from the local domestic violence service to offer support along with a safety plan. But she is “shit scared to leave, and to report them,” John says, “because if the police don’t lift them, but they find out she’s dobbed them in, she’s dead.”

Twenty three years after Ann Cryer first spoke out about the widespread gang-related abuse of children in her constituency, little has changed — except that countless more girls have had their lives destroyed.

***

*Names have been changed.