- Semiautonomous drone deployment: Ukrainian forces now rely on drones that can switch from pilot control to AI-guided terminal strikes, exemplified by Bumblebee and other systems achieving over 1,000 combat flights.

- Underdog module: NORDA Dynamics created an aftermarket module that enables F.P.V. drones to lock onto targets and complete terminal attacks autonomously, extending range to roughly 2 kilometers.

- Swarm coordination: Sine Engineering’s Pasika app lets a single operator autonomously launch, loiter, and transfer control among dozens of drones, creating rapid-sequence swarm strikes.

- Counter-jamming navigation: Vermeer’s Visual Positioning System equips deep-strike drones with camera-based navigation that bypasses GPS denial, guiding missions across contested airspace.

- Schmidt-backed platforms: Eric Schmidt’s venture supplies Bumblebee, Hornet, Merops, and other AI-enabled drones to elite Ukrainian brigades, combining target recognition, terminal guidance, and jamming resistance.

- Human oversight emphasis: Developers and operators maintain humans designate targets, and Ukrainian doctrine aims to keep people in the loop despite growing autonomous capabilities.

- Ethical concerns: Technologists and activists warn that AI-enabled targeting raises moral questions about dehumanized kill decisions, especially once algorithms pursue people independently.

- Strategic implications: Ukrainian leaders treat AI-enhanced drones as essential to national defense, while Western observers worry existing militaries are unprepared for the emerging autonomous warfare landscape.

In the past year, drone warfare in Ukraine has undergone a chilling transformation.

Most drones require a human pilot. But some new Ukrainian drones, once locked on a target, can use A.I. to chase and strike it — with no further human involvement.

This is the story of how the battlefield became the birthplace of a powerful new weapon.

On a warm morning a few months ago, Lipa, a Ukrainian drone pilot, flew a small gray quadcopter over the ravaged fields near Borysivka, a tiny occupied village abutting the Russian border. A surveillance drone had spotted signs that an enemy drone team had moved into abandoned warehouses at the village’s edge. Lipa and his navigator, Bober, intended to kill the team or drive it off.

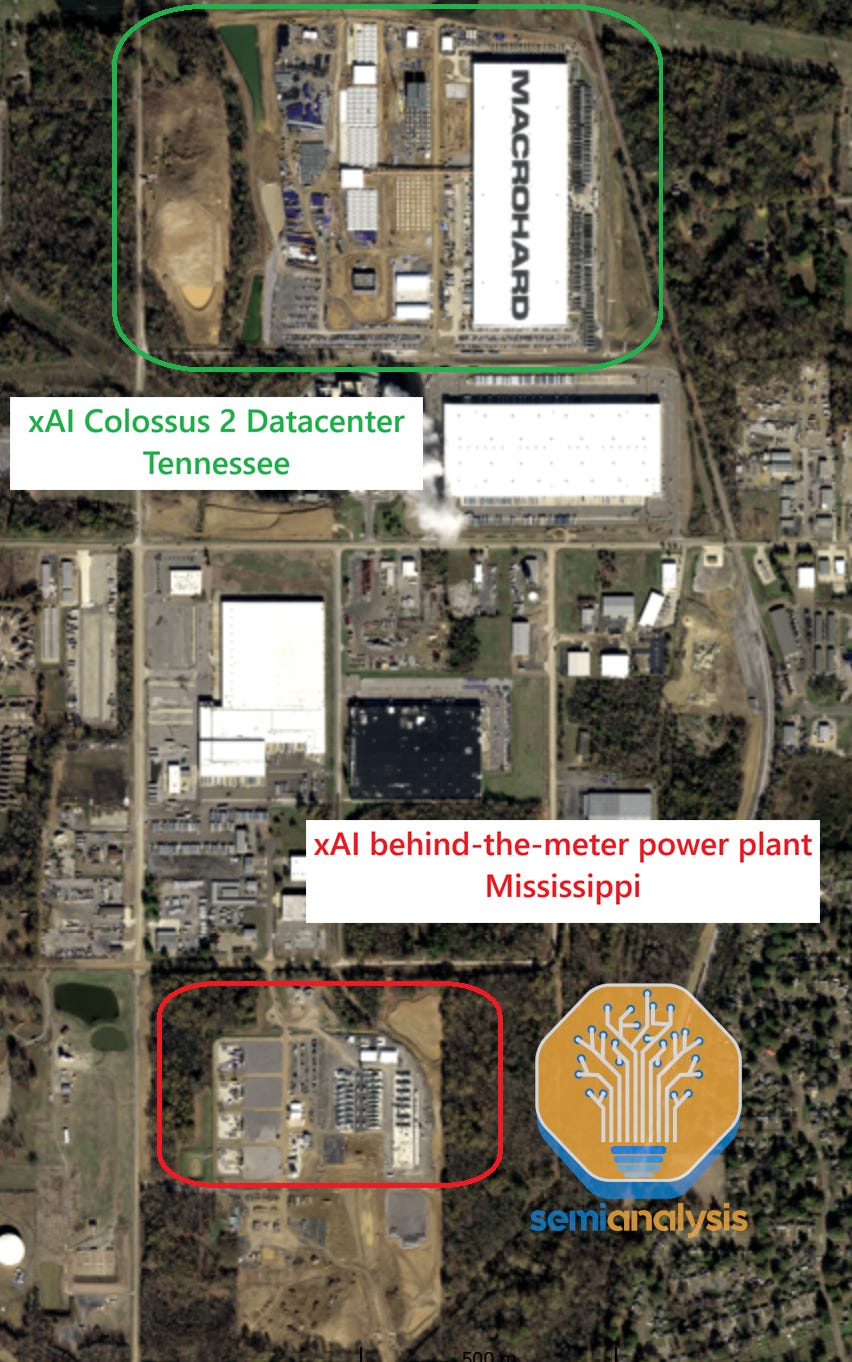

Another pilot had twice tried hitting the place with standard kamikaze quadcopters, which are susceptible to radio-wave jamming that can disrupt the communication link between pilot and drone, causing weapons to crash. Russian jammers stopped them. Lipa had been assigned the third try but this time with a Bumblebee, an unusual drone provided by a secretive venture led by Eric Schmidt, the former chief executive of Google and one of the world’s wealthiest men.

Bober sat beside Lipa as he oriented for an attack run. From high over Borysivka, one of the Bumblebee’s two airborne cameras focused on a particular building’s eastern side. Bober checked the imagery, then a digital map, and agreed: They had found the target. “Locked in,” Lipa said.

With his right hand, Lipa toggled a switch, unleashing the drone from human control. Powered by artificial intelligence, the Bumblebee swept down without further external guidance. As it descended, it lost signal connection with Lipa and Bober. This did not matter: It continued its attack free of their command. Its sensors and software remained focused on the building and adjusted heading and speed independently.

Another drone livestreamed the result: The Bumblebee smacked into an exterior wall and exploded. Whether Russian soldiers were harmed was unclear, but a semiautonomous drone had hit where human-piloted drones missed, rendering the position untenable. “They will change their location now,” Lipa said. (Per Ukrainian security rules, soldiers are referred to by their first name or call sign.)

Throughout 2025 in the war between Russia and Ukraine, in largely unseen and unheralded moments like the warehouse strike in Borysivka, the era of killer robots has begun to take shape on the battlefield. Across the roughly 800-mile front and over the airspace of both nations, drones with newly developed autonomous features are now in daily combat use. By last spring, Bumblebees launched from Ukrainian positions had carried out more than 1,000 combat flights against Russian targets, according to a manufacturer’s pamphlet extolling the weapon’s capabilities. Pilots say they have flown thousands more since.

Bumblebee’s introduction raised immediate alarms in the Kremlin’s military circles, according to two Russian technical intelligence reports. One, based on dissection of a damaged Bumblebee collected along the front, described a mystery drone with chipsets and a motherboard “of the highest quality, matching the level of the world’s leading microelectronics manufacturers.” The report noted the sort of deficiencies expected of a prototype but ended with an ominous forecast: “Despite current limitations,” it declared, “the technology will demonstrate its effectiveness” and its range of uses “will continue to expand.”

That conclusion was prescient but understated, for the simple reason that Bumblebees hardly fly alone. Under the pressures of invasion, Ukraine has become a fast-feedback, live-fire test range in which arms manufacturers, governments, venture capitalists, frontline units and coders and engineers from around the West collaborate to produce weapons that automate parts of the conventional military kill chain. Equipped with onboard proprietary software trained on large data sets, and often run on off-the-shelf microcomputers like Raspberry Pi, drones with autonomous capabilities are now part of the war’s bloody and destructive routine.

In repeated visits to arms manufacturers, test ranges and frontline units over 18 months, I observed their development firsthand. Functions now performed autonomously include: pilotless takeoff or hovering, geolocation, navigation to areas of attack, as well as target recognition, tracking and pursuit — up to and including terminal strike, the lethal endpoint of the journey. Software designers have also networked multiple drones into a shared app that allows for flight control to be passed between human pilots or for drones to be organized into tightly sequenced attacks — a step toward computer-managed swarms. Weapons with these capabilities are in the hands of ground brigades as well as air defense, intelligence and deep-strike units.

Image

Bumblebee attack drones at a combat testing range outside Kharkiv, Ukraine.Credit...Finbarr O'Reilly for The New York Times

Drones under full human control remain far more abundant than their semiautonomous siblings. They cause most battlefield wounds. But unmanned weapons are crossing into a new frontier. And while no publicly known drone in the war automates all steps of a combat mission into a single weapon, some designers have put sequential steps under the control of artificial intelligence. “Any tactical equation that has a person in it could have A.I.,” said the founder of X-Drone, a Ukrainian company that has trained software for drones to hunt for and identify a stationary target, like an oil-storage tank, and then hit it without a pilot at the controls. (The founder asked that his name be withheld for security reasons.)

The Kremlin’s forces are also adopting A.I.-enhanced weapons, according to examinations of downed Russian drones by Conflict Armament Research, a private arms-investigation firm. With both sides investing, Mykhailo Fedorov, Ukraine’s first deputy prime minister, said A.I.-powered drones are at the center of a new arms race. Ukraine’s defenders must field them in large numbers quickly, he said, or risk defeat. “We are trying to stimulate development of every stage of autonomy,” he said. “We need to develop and buy more autonomous drones.”

To be sure, the familiar weapons of modern battlefields, all under human control, have caused immeasurable harm to generations of soldiers and civilians. Even weapons celebrated by generals and pundits as astonishingly precise, like GPS-guided missiles or laser-guided bombs, have often struck the wrong places, killing innocents, often without accountability. No golden age is being left behind. Rather, semiautonomous drones compound existing perils and present new threats. Peter Asaro, vice chair of the Stop Killer Robots Campaign and a philosopher and an associate professor at the New School, warned of rising dangers as weapons enter unmapped practical and ethical terrain. “The development of increasing autonomy in drones raises serious questions about human rights and the protection of civilians in armed conflict,” he said. “The capacity to autonomously select targets is a moral line that should not be crossed.”

The concept of a killer robot is vague and prone to hype, invoking T-800 of “The Terminator,” an adaptive mobile killing machine deployed by an artificial superintelligence, Skynet, that perceives humanity as a threat. Nothing close exists in Ukraine. “Everybody thinks, Oh, you are making Skynet,” said a captain responsible for integrating new technology into the 13th Khartia Brigade of Ukraine’s National Guard, one of the country’s most sophisticated units, in which Lipa and Bober serve. “No, the technology is interesting. But it’s a first step and there are many more steps.”

The captain and other technicians working with A.I.-enhanced weapons said they tend to be brittle, limited in function and less accurate than weapons under skilled human control. Many have a short battery life and brief flight times. Autonomous weapons with sustained endurance, high flexibility and the ability to discern, identify, rank and pursue multiple categories of targets independent of human action have yet to appear, and they would require, the captain said, “a waterfall of money” plus much imagination and time. “It’s like the staircase of the Empire State Building,” he said. “That’s how many steps there are, and we are inside the building but only on the first floor.”

As a safeguard against A.I.-powered weapons slipping the leash, humanitarians and many technologists have long advocated keeping “humans in the loop,” shorthand for preventing weapons from making homicidal decisions alone. By this thinking, a trained human must assess and approve all targets, as Lipa and Bober did, ideally with the power to abort an individual strike and a kill switch to shut an entire system down. Strong guardrails, the argument goes, are necessary for accountability, compliance with laws of armed conflict, legitimacy around military action and, ultimately, for human security.

Schmidt has emphasized the necessity of human oversight. But at the end of a flight, some semiautonomous weapons in Ukraine can already identify targets without human involvement, and many Ukrainian-made systems with human override are inexpensive and could be copied and modified by talented coders anywhere. Some of those designing A.I.-enhanced weapons, who consider their development necessary for Ukraine’s defense, confess to unease about the technology that they themselves conjure to form. “I think we created the monster,” said Nazar Bigun, a young physicist writing terminal-attack software. “And I’m not sure where it’s going to go.”

The Dawn of Autonomous Attack

Bigun’s own journey exemplifies how the duration and particulars of the war incentivized the creation of semiautonomous weapons. When Russia rolled mechanized divisions over Ukraine’s border in 2022, Bigun was leading a team of software engineers at a German tech start-up. In early 2023, he founded a volunteer initiative for the military that eventually manufactured 200 first-person-view (F.P.V.) quadcopters a month. It was a significant contribution to Ukraine’s war effort at a time when low-cost and explosive-laden hobbyist drones, not yet widely recognized as the transformative weapons they are, remained in short supply. His focus might have remained there. But as he and his peers heard from frontline drone pilots, they became concerned about declining success rates of kamikaze drones in the face of defensive adaptations, and they joined the search for solutions.

The problems were many. As more drones took flight, both sides developed physical and electronic countermeasures. Soldiers erected poles and strung mesh to snag drones from the air, and they covered the turrets and hulls of military vehicles with protective netting, grates or welded cages. Among the most frustrating countermeasures were jammers that flooded the operating frequencies used for flight control and video links, generating electronic noise that reduced signal clarity in pilot-to-drone connections. The systems became standard around high-value targets, including command bunkers and artillery positions. They also appeared on expensive mobile equipment, like air-defense systems, multiple-rocket launchers and tanks.

Image

A Ukrainian military vehicle traveling under a web of netting meant to protect against drone attacks near the frontline city Pokrovsk.Credit...Finbarr O'Reilly for The New York Times

This complex puzzle led to the creation of drones that fly on fiber-optic cables, one solution that has appeared on the battlefield. It also fueled Bigun’s interest in a form of computer-enabled attack, known as last-mile autonomous targeting, in which computer vision and autonomous flight control would guide drones through the final stage of attack without radio-signal inputs from a pilot. Such systems promised another benefit as well: They would increase the efficacy of strikes at longer range and over the radio horizon, when terrain or the Earth’s curvature interfere with a steady radio signal.

In theory, the technical remedy was simple. When pilots anticipated a break in communications, they could pass flight control to an automated substitute — a powerful chipset and extensively trained software — that would complete the mission. With this tech coupled to onboard sensors and a camera, the pilot could lock the mini-aircraft on a target and release the drone to strike alone. The company Bigun co-founded in 2024, NORDA Dynamics, did not manufacture drones, so it set to work creating an aftermarket component to attach to other manufacturers’ weapons. With it, a pilot would still fly the drone from launch until it neared a target. Then the pilot would have the option of autonomous attack.

Boosted by funding from the Ukrainian government and venture capital firms, NORDA spent much of 2024 testing a prototype that evolved into its flagship offering, Underdog, a small module that fastens to a combat drone. When flying an Underdog-equipped quadcopter, a pilot with F.P.V. goggles still controls the weapon from takeoff almost to destination. But in a flight’s final phase, the pilot has the choice — via an onscreen window that zooms in on objects of interest, like a building or car — of approving an autonomous attack in a process called pixel lock. At that moment, Underdog takes over.

Underdog began with tests on stationary objects, but after repeated updates, its software chased moving quarry. Range extended, too. Early modules allowed 400 meters of terminal attack; by summer 2025, with the fifth version of NORDA’s software, pixel lock reached 2,000 meters — about 1.25 miles. By then the modules had been distributed to collaborating F.P.V. teams at the front. “We have some very good feedback,” Bigun said. A company bulletin board listed early hits, among them Russian artillery pieces, trucks, mobile radar units and a tank.

Image

Nazar Bigun (center), co-founder and chief executive of the Ukrainian defense-tech start-up NORDA Dynamics, with colleagues on lunch break from a nearby arms expo.Credit...Finbarr O'Reilly for The New York Times

One summer afternoon in western Ukraine, Bigun and several employees arrived at a tree line of wild pear, apple and plum dividing agriculture fields. Cows meandered past, swishing tails to shoo flies. Two white storks glided to the ground, alighted and picked their way through the furrows, hunting. NORDA’s technicians sent a black S.U.V. with a driver and two-way radio to drive along the fields.

A test pilot, Janusz, a Polish citizen who had volunteered as a combat medic in Ukraine before joining the company, sat in the van wearing goggles and holding a hand-held radio controller. Once the S.U.V. drove away, he commanded an unarmed F.P.V. drone through liftoff. “I’m flying,” he said over the radio.

The video feed showed golden fields and green windbreaks, overlaid with dirt roads. The drone climbed to about 200 feet. Its camera revealed the black S.U.V. less than a mile away. Onscreen, Janusz slipped a square-shaped white cursor over the image of the vehicle. A pop-up window appeared in the upper-left corner containing a stabilized close-up of the S.U.V. With his left hand, Janusz selected pixel lock. The word “ENGAGE” appeared within a red banner onscreen. Thin black cross-hairs settled on the center of the S.U.V.

Janusz lifted his hands from the controller. From an altitude of about 215 feet, the drone entered a slow dive. Within seconds it had flown almost to the moving S.U.V.’s windshield. Janusz switched back to human piloting and banked the quadcopter away, sparing the vehicle damage from impact.

At his command, the drone climbed, spun around and resumed pursuit, this time from more than 500 feet up. Its prey bounded along a road. Janusz lined up the cursor and engaged pixel lock again. The drone entered a second independent dive, accelerating toward the fleeing car. Once more Janusz overrode the software at the last moment. The quadcopter buzzed so closely that the whine of its engines was picked up by the vehicle’s two-way radio and broadcast inside the pilot’s van. Janusz smiled.

He swung the drone around, showing the van he sat in. The cursor briefly presented the possibility of pixel lock on himself. Janusz chuckled and steered the weapon away, back toward the S.U.V. The driver’s voice crackled over the radio. “We will right now make a turn,” he said.

For the next half-hour, the driver’s maneuvers made no difference. No matter what he did, the drone, once pixel-locked, closed the distance autonomously, harassing the moving vehicle with the tenacity of an obsessed bird.

Compared with conditions common in war, the field exercise was simple. Groundspeeds were slow, flights were by daylight, no power lines or tree branches blocked the way. The drone maintained a constant line of sight with the S.U.V., and the software had to lock on a lone vehicle, not on a target weaving through traffic or passing parked cars. But with more training and computational power, the software could be improved to discern and prioritize military targets based on replacement cost or degree of menace, or fine-tuned to strike armored vehicles in vulnerable places, like exhaust grates or where turrets meet hulls. It might be trained to hunt most anything at all — a bus, a parked aircraft, a lectern where a speaker is addressing an audience, a step-down electrical transformer distributing power to a grid.

Image

An employee from NORDA Dynamics launching a Dart-2 fixed-wing strike drone for engineers to fine-tune their automated flight software. Credit...Finbarr O'Reilly for The New York Times

For Bigun, the natural worry that such technology could be turned against civilians has been overridden by the imperatives of survival. Beyond coding, his work involves interacting with arms designers from Ukraine and the West, including at weapons expositions, where he seeks partners and clients. But he often visits the Field of Mars, a cemetery in Lviv that is a repository of solemn memory and raw pain.

Bigun’s great-uncle was a Ukrainian nationalist during the totalitarian rule of Stalin. For this, Bigun’s grandfather was deemed an enemy of the state by association, and shipped to Siberia at age 16. Both men are buried on the grounds, where they have been joined by a procession of soldiers killed since the full invasion. On an evening following one of Bigun’s arms-show appearances, mourners at the field sanded tall wooden crucifixes by hand, then reapplied lacquer; a widow sat beside a grave talking to her lost husband as if he were sipping tea in an opposite chair; a family formed a semicircle around a plot covered in flowers with each member taking turns catching up a deceased soldier on household news. The field reached full capacity in December — almost 1,300 graves — prompting Lviv to open a second cemetery for its continuing flow of war dead. Just before Christmas, the second field held 14 fresh mounds.

Bigun abhors the need for these places. But beside commemorations of friends snatched early from life by the war, he said, he finds inspiration to continue his work. “This is where I feel the price we pay,” he said, “and it motivates me to move forward.” By the end of the year, NORDA Dynamics had provided frontline units fighting in the East more than 50,000 Underdog modules.

The Rise of the Swarm

The Ukrainian military’s hard pivot to drone warfare helped save the nation. For almost four years, while fielding the world’s first armed force to reorganize around unmanned weapons, it blunted the ground assaults of Russia’s far larger military. It continues to do so even as the Kremlin replenishes its thinned divisions, drawing from oil-state revenue and a population at least four times the size of Ukraine’s.

But the weapon has a limit. Almost all short-range kamikaze drones — a primary means of stopping advancing Russian soldiers — are flown by individual pilots, one at a time. Each is a vicious aerial acrobat: From airspeeds up to 70 miles an hour, small multicopters can stop, hover, turn and fly off in new directions for minutes on end, traits empowering pilots to find, chase and kill their human victims with chilling efficacy. And yet during sustained Russian attacks, typical frontline conditions can force drone teams to fight slowly. The pace is set by the duration between each drone’s launch and final approach, which at common standoff distances often stretches past 20 minutes. When Russian soldiers infiltrate in large numbers, single-drone strike sequences can feel slow and insufficient. Between sorties, enemies escape.

Given the enduring challenge of massing drone firepower, designers of autonomous combat-drone technology have sought to assemble drones into swarms, the allure of which is obvious to a nation under attack. Even small swarms would allow pilots to concentrate multiple weapons in punishing rapid-fire strikes, stiffening defenses and raising the prospect of overwhelming machine-only attacks.

Not long after Janusz’s terminal-attack flights, technicians from another Ukrainian company, Sine Engineering, gathered near a rural village to train drone pilots on its entrant to the swarm-tech field, called Pasika, the Ukrainian word for apiary. The heart of Pasika’s hardware is its radio modems — small frequency-hopping transceivers that act as beacons for flying drones. In flight, each quadcopter’s altitude and location update several times a second by measuring the differences in arrival times of radio signals from several known positions. Pasika software also provides automated flight control. At its current stage of development, a sole pilot can manage dozens of drones through autonomous launch, navigation and hovering — a pre-attack phase during which massed drones loiter pending instructions.

During a multiday training session for quadcopter teams fresh from frontline duty, Pavlo, a former infantryman who serves as Sine Engineering’s liaison to combat brigades, coached pilots as they practiced. The tech was futuristic but the scene was characteristically rural Ukrainian. The test range, hectares of hayfield and sunflower, was not secured behind fences or watched over by control towers. The students, including pilots from Kraken 1654 Unmanned Systems Regiment of the Third Army Corps and Samosud Team, a drone unit of the 11th National Guard Brigade, worked in casual clothes and colorful T-shirts, eating artisanal pizzas as they tinkered. A small horse stood tethered to a stake beside a wooden cart, chewing grass into a flat circle.

Via an app, the pilots took turns ordering drones to launch and navigate to a point on the map. Unaided by human hand, quadcopters rose in the air and sped off over the countryside to loiter together about a mile away. Tablet screens revealed their progress. A video feed from each quadcopter showed rolling cropland below. The pilots kept their hands off the controls. A rusty tractor puttered past.

Image

Soldiers attending training with Sine Engineering, a Ukrainian defense-tech company. Sine’s product, Pasika, lets a single operator manage several drones at a time, hitting targets in quick-succession “swarm attacks.”Credit...Finbarr O'Reilly for The New York Times

For a final exercise, a pilot with the call sign Kara directed her team to gather two drones autonomously over an opposite field. Another team flew three more. Once the drones reached their loitering point, Kara said, pilots would take control and fly them manually toward targets to practice a massed attack.

Pasika also allows pilots on the app to exchange control of individual drones among themselves. In this way, any pilot could use them to attack across a short distance with brief intervals between strikes. The concept could be extended further. With Pasika or a similar system, quadcopters stockpiled in boxes near a front could be commanded by a sole operator, whether A.I. or human, creating a dense swarm of drones to face ground attacks without delay.

Multiplying a sole soldier’s combat power in these ways made sense to Kara, whose brother, husband and husband’s twin brother all rose to resist the Russian invasion. Ukraine grants humanitarian discharges to siblings of service members killed in action, and when her brother-in-law was killed, her husband transferred to the reserve. Upon his return home, Kara enlisted and became a drone pilot. Her call sign means retribution.

Pavlo, too, had his motivations. In summer 2022, he was almost killed by conventional military incompetence when his commander gathered more than 300 soldiers in buildings in Apostolove, a city north of Crimea. Dense public garrisoning offers rich targets for long-range weapons, which arrived as a barrage of S-300 missiles. Pavlo was inside a middle school when the first missile exploded in the yard. He huddled with others under a stairwell. The next missile hit the school squarely, leaving him pinned under rubble as yet another roared in and exploded. At least four peers in the stairwell died. Pavlo suffered burns on his head, torso and arms. After convalescing, he trained as a drone pilot and began flying reconnaissance missions behind Russian lines. Experience told him Ukraine needed high-tech solutions to secure its future. “It woke something in me,” he said, of nearly dying because of an old-school infantry commander’s lazy mistake. “An instinct for survival on a more sophisticated level.”

Can A.I. Replace GPS?

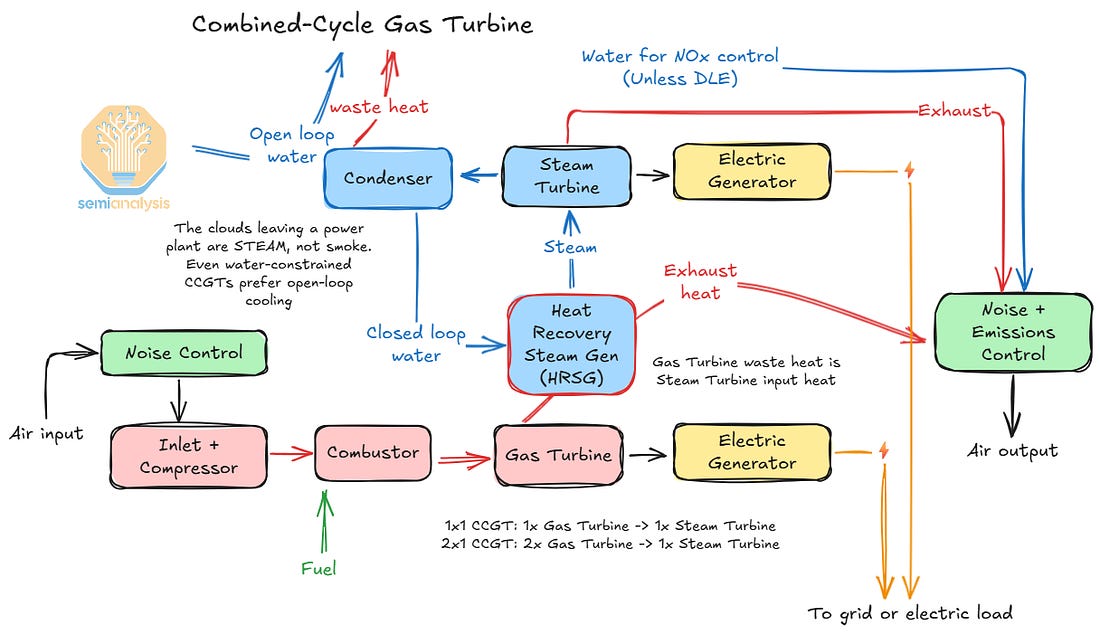

In late 2023, Brian Streem, the founder of a niche drone-cinematography business, was meeting with a Latvian company about putting a visual navigation system on long-range drones when one of his hosts suggested he bring his ideas to Ukraine. Deep-strike drones, essentially slow-flying cruise missiles that can travel hundreds of miles, require precise navigation to move through foreign airspace for hours, and to follow zigzag routes that change altitude frequently to evade air defenses. Ukraine had high hopes for its growing deep-strike arsenal to target Russian fuel and arms depots. But Russia had shut down GPS over the front and its western territory. Vaunted GPS-reliant systems were failing. The Latvian company thought Streem had a solution.

Streem was new to the arms business, and his journey had been anything but direct. A native of Bayside, Queens, he graduated from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts in 2010 and started producing independent films and commercials. His work indulged a fascination for difficult photographic challenges, which led him to drones and the creation of a company, Aerobo, that shot aerial footage for music videos and Hollywood productions, including “A Quiet Place,” “Spider-Man: Homecoming” and “True Detective.”

Image

Brian Streem, the founder of Vermeer, a company that develops visual positioning systems (V.P.S.) that enable drones to navigate without GPS assistance.Credit...Finbarr O'Reilly for The New York Times

Aerobo’s services were in demand. Streem might easily have settled in, but he found working in Hollywood to be stressful and sometimes stultifying. Every shoot had to be both technically perfect and aesthetically pleasing, even beautiful. “If you think military drone missions are hard,” he says, “try making Steven Spielberg happy.” Moreover, the available tech, though expensive, felt janky and resistant to graceful use. Quadcopters were just beginning to enter markets, and the larger drones Aerobo flew required at least two people — a pilot controlling the airframe and an operator moving a camera system on a gimbal, “in this kind of dance,” Streem said. Frustrated with the equipment and unsure how to scale up his business, he shuttered Aerobo in 2018, renamed the company Vermeer and started developing software to make drone cinematography more intuitive.

Revenue dried up. In 2019, feeling desperate, he attended an investor speed-dating seminar in Buffalo and sat across from Warren Katz, an entrepreneur who directed a U.S. Air Force start-up accelerator that funded military tech. Streem explained what he was working on. Katz suggested that the Air Force “would be very interested in what you’re doing.” Streem was astonished. He was not a weapons designer; one of his last professional collaborations was a music video by the rapper Cardi B. “If you’re coming to me for help,” he said, “we’re in a lot of trouble.”

“Well,” Katz said, “you might be surprised.”

Katz urged him to apply to a program for start-ups of Air Force interest. Streem hastily filled out forms. A month later, Vermeer was selected. Streem moved to Boston, began meeting officials from the Pentagon and was at once startled and pulled in. “I realized, OK, I don’t know much about A.I.,” he said. “But as I am talking to these people, I’m kind of thinking to myself, I don’t think they know much about A.I., either.”

Streem is amiable, persistent and energized by a seemingly instinctual inclination for sales. When Covid closed offices, he retreated to a lakeside cabin and created an internet-scraping tool that yielded the email addresses of more than 50,000 military officers. From social isolation, Streem started writing them to discuss what they saw as the military’s most pressing technical challenges. Answers clustered around reliance on GPS. Entire arsenals of American military equipment, he heard, depended on a satellite navigation system that a sophisticated enemy could disable. The more he learned, the more his ideas clicked into place: I may know how to solve these people’s problems, he thought.

His idea was straightforward. He would program autopilot software to process visual information from multiple cameras, compare it with onboard three-dimensional terrain maps, then triangulate to fix a weapon’s location. Called a visual positioning system, or V.P.S., the software could be loaded onto any number of flying platforms, equipping them to navigate over terrain with no satellite link at all. It could not be jammed or spoofed, because it would neither emit nor receive a signal.

Image

V.P.S. units designed by Vermeer sitting in storage. The system uses cameras to analyze an environment and match it to 3-D maps, determining precise locations even when satellite signals are jammed or unavailable.Credit...Finbarr O'Reilly for The New York Times

In early 2024, Streem rode a train from Warsaw to Kyiv and messaged Ukrainian officials on LinkedIn, introducing himself and his work. Soon he was invited to the Cabinet of Ministers building, where he made his way past the sandbagged entrance, attended an impromptu birthday party for a government employee and was led into a room with an official who wanted to put Vermeer’s modules on deep-strike drones. The building’s power was out. The office was dark. Ukraine was short on money, soldiers and time. The official did not mince words. “He essentially had a big map of Russia and Ukraine behind him, and immediately he started telling me about targets we’re going to hit,” Streem said.

Streem had talked his way into Ukraine’s war. Over the next year, he met drone manufactures around the country, tested prototypes on various drones and released the VPS-212, a roughly one-pound box with two cameras and a minicomputer. Assembled in an office beside a bagel shop in Brooklyn, the module can fix its location at speeds up to 218 m.p.h. — not fast enough for a proper cruise missile, but sufficient for most deep-strike drones. By summer 2025, Vermeer’s technicians were helping soldiers attach them to drones flown by several units that attack strategic targets in Russia. For security reasons, Vermeer does not publicly discuss specific strikes, but Streem and a Vermeer employee in Ukraine said V.P.S. modules had guided drones to verified hits.

With these results, Vermeer emerged as a winner in the scrum for contracts and funding, raising $12 million in a recent round that included the venture capital firm Draper Associates. In 2025, it attracted renewed attention from the Pentagon, which proposed attaching Vermeer’s V.P.S. to new fleets of deep-strike drones of its own. The U.S. Air Force also contracted the company to develop a similar system that would mount atop drones to look skyward and navigate celestially, like an A.I.-enabled sextant for precision flight above clouds or over water.

By then, Streem was immersed in his new line of work. Late in 2025, he sent me a tongue-in-cheek text about his passage from filmmaker to manufacturer of self-navigating camera modules that steer high-explosive payloads into Russia. “Stream reclined in his chair, vapor from his vape pen curling lazily between his fingers, as if the war beyond the walls were a distant rumor rather than the air he breathed,” the text read. The prose, he said, had been generated by A.I. It misspelled his name.

The Great Convergence

Few people could be as conversant in the promises and the perils of A.I.-enhanced weapons as Eric Schmidt, who served as chairman of the U.S. Defense Innovation Board from 2016 to 2020 and led the bipartisan National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence from 2018 to 2021. Since working with Ukraine, he has been mostly tight-lipped about his wartime ventures, which have operated under multiple names, including White Stork, Project Eagle and Swift Beat. Through a public-relations firm, he declined to respond to multiple requests for comment for this article. But in a talk at Stanford in 2024 he called himself “a licensed arms dealer.” And by that fall, his operation had hired former Ukrainian soldiers to meet with active drone teams near Kyiv and train them on semiautonomous weapons to take to the front.

Ukrainian units vary widely in quality, and Schmidt’s team appears to have chosen carefully. Those collaborating with his operation are among Ukraine’s best managed, with reputations for innovation, battlefield savvy and sustained success against much larger Russian forces. Among them are the Khartia Brigade, which formed in 2022 to defend Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second largest city, and grew into a disciplined, tech-centric battlefield force. With an extensive fleet of aerial and ground drones, modern command posts and an ethos of data-driven decision-making, Khartia operates from hiding in the city and countryside. Its officers track Russian actions with networked ground cameras and sensors on the battlefield and reconnaissance drones in the air. The raw information is run through software producing outputs that resemble, its analysts say, “Moneyball” goes to war.

“We collect a lot of statistics and data,” said Col. Daniel Kitone, the brigade commander. “In conditions where resources are limited, we are providing for efficiency, and sometimes statistics give interesting answers that drive operations.” Rapid processing of multiple forms of surveillance data, the brigade’s officers say, can illuminate patterns, like recurring times when Russian troops resupply positions. They then use these insights to synchronize strike-drone flights with anticipated Russian movement, hoping to catch targets in the open.

Image

Khartia Brigade soldiers on shift in an underground command center in northeastern Ukraine.Credit...Finbarr O'Reilly for The New York Times

Bumblebee’s combat trials began with multiple brigades last winter. One test pilot, who flew the drone near Kupiansk in December 2024, said his team put the new quadcopters through progressively harder tests against Russian positions and vehicles, with the manufacturer’s engineers on call for technical assistance. “During this whole time, the product constantly improved,” the pilot said. “We constantly provided the developers with feedback: what works, what really does not work, which features are useful and which are not.” As with most A.I. products, more data can lead to smarter software. During Bumblebee’s quiet rollout, mission data from combat flights was logged and analyzed, several pilots said. Developers then pushed software updates to brigades that drone teams could download remotely.

One early attack hit the entrance to a root cellar where Russian soldiers sheltered. As Bumblebees evolved, pilots flew them further distances and against moving targets. In January 2025, an autonomous Bumblebee attack stopped a Russian logistics truck as it drove behind enemy lines, the test pilot said. In April, after more updates, Bumblebees flew autonomously against a Russian armored vehicle driving with a jammer. The vehicle was so covered with anti-drone protective measures that it resembled a porcupine. It absorbed the first strike and kept moving. A second Bumblebee hit immobilized it. This amounted to a milestone: A vehicle with all the protective steps Russia could muster had been removed from action.

Bumblebee’s entrance to the war had been shrouded in secrecy. But with strikes like that the hush could not last. Russia took note. Its soldiers outside Kupiansk and Kharkiv, where early Bumblebee sorties occurred, reported that these strange new drones seemed impervious to interference: They flew smoothly through jamming and kept racking up hits. The only sure way to stop them was to shoot them down.

Two days after the strike on the armored vehicle, the Center for Integrated Unmanned Solutions, a Russian drone-manufacturing business outside Moscow, issued findings from its analysis of a downed Bumblebee recovered near the front. It nicknamed the quadcopter Marsianin, Russian for “Martian,” based on the assumption that the prototypes descended from NASA’s Ingenuity program, which developed a small autonomous helicopter that flew on Mars. The report’s author declared that Ukraine had fielded an A.I.-enhanced drone capable of “operating in total radio silence” while flying complex routes and maneuvers “completely independent of navigation systems” — or even a human pilot.

The following month, the Novorossiya Assistance Coordination Center, a Russian ultranationalist organization that provides training and equipment to Russian soldiers, published a second analysis, a 49-page report loaded with warnings. Through open-source sleuthing, its author had found a photo of a Bumblebee posted by a Reddit user who in late 2024 obtained a broken specimen from garbage discarded at a Michigan National Guard facility. With that evidence, the author, Aleksandr Lyubimov, who organizes combat-drone exhibitions in Russia, echoed the first analyst’s suspicion that the Bumblebee had some connection to the United States. He noted that it “poses a serious threat” and asserted, accurately, that “its current use does not yet reveal its full capabilities and is most likely of a combat testing nature.” Nonetheless, he added, “there are no effective countermeasures against it, and none are expected in the near future.”

The Bumblebee’s resistance to jamming, according to a sales pamphlet in limited circulation in Ukraine, was tied in part to “redundant comms,” radio-wave frequency hopping and navigation by visual inertial odometry — technical solutions to signal jamming. But what made the weapon remarkable was not any one autonomous feature. It was the convergence of several.

According to the pamphlet, which claimed an “over 70-percent direct-hit rate via autonomous terminal guidance,” Schmidt’s quadcopters are also capable of autonomous target recognition. By overlaying bright green squares on items of interest appearing in video feeds, pilots said, Bumblebee’s software highlights potential targets, including foot soldiers, bunkers, vehicles and other aerial drones, often before human pilots can spot them. The combination of features, they said, result in an autonomous attack capability more robust and reliable than others available to date.

Bumblebees can also be controlled over the internet, which Lipa did in the strike in Borysivka. This keeps pilots away from the front, and from many weapons that might counterattack. In theory, as long as a Bumblebee’s ground station maintains a stable Wi-Fi or broadband connection, a pilot can operate it from almost anywhere — a capability demonstrated this past summer when Schmidt visited Kyiv and observed a Khartia team flying a Bumblebee released by a ground crew outside Kharkiv. According to a review of footage and people familiar with the mission, the drone passed over the lines and hit a four-wheel-drive Russian military van, known as a bukhanka — from roughly 300 miles away.

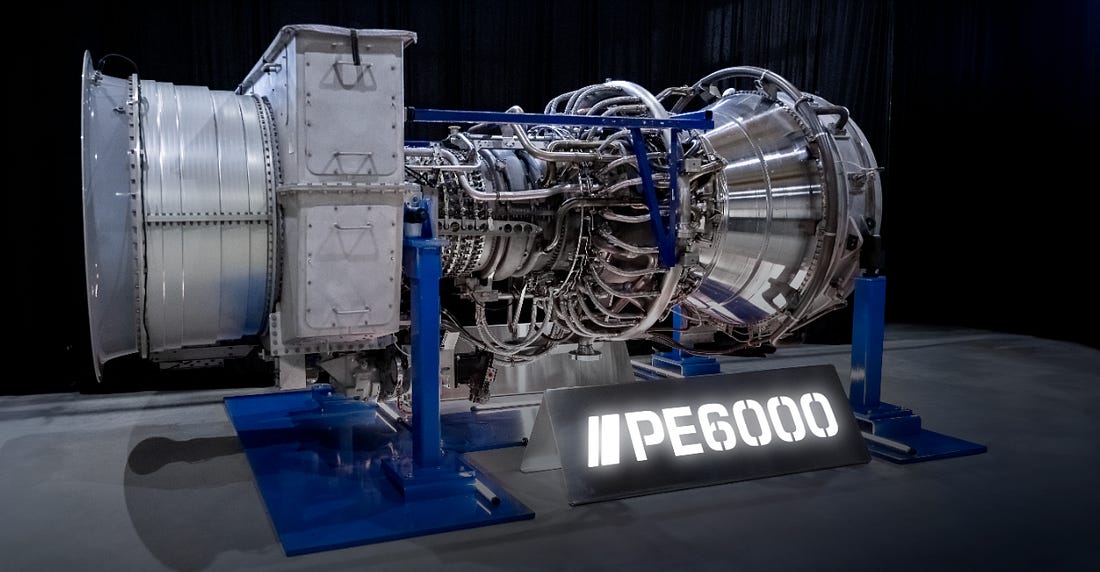

A Billionaire’s Growing Fleet

The Bumblebee is not a one-off project. It’s part of an experimental pack. Schmidt’s operation has also supplied Ukrainian units with a medium-range fixed-wing strike drone with a two-meter wingspan, marketed under the name Hornet, according to another sales pamphlet from early 2025. Like Bumblebee, it has A.I.-powered target recognition and terminal-attack guidance, along with jam-resistant communication and navigation systems. The pamphlet advertised an 11-pound payload, a cruise speed of 62 m.p.h. and range exceeding 90 miles. “Our A.I.-powered platform processes battlefield data in real time, adapting to changing conditions without human intervention,” the pamphlet says. “Neutralize more targets at a fraction of legacy system costs. Deploy at scale to achieve overwhelming force multiplication against sophisticated threats.” The pamphlet claimed a “future monthly production” of more than 6,000 units.

Schmidt has also become an ally in Ukraine’s defense against Shaheds, the Iranian-designed long-range drones that pummel Ukrainian cities almost nightly. In July 2025, he appeared with Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelensky, to announce a strategic partnership to provide Ukraine with A.I.-powered drones, with an emphasis on an interceptor system known as Merops. Ukraine was developing its own human-piloted anti-Shahed drones, and had some early successes. But Schmidt’s weapons, Ukrainian officials said, were more effective. Mykhailo Fedorov, Ukraine’s first deputy prime minister, showed videos of them striking Shaheds at high speed. Merops had a hit rate as high as 95 percent, he said. (After its combat trials in Ukraine, Merops is now being deployed on NATO’s eastern flank.)

Ukrainian pilots and officers say Schmidt’s products have shown more promise than most, though reviews for Bumblebee have not been universally glowing. The weapon has no night cameras, limiting flights to daytime. Lyubimov, the Russian technical analyst, described the drone as inadequately weather resistant. “The design exhibits many ‘childhood flaws,’” he wrote. But Schmidt’s technicians are available on the Signal app and responsive to suggestions, said Serhii, a Bumblebee combat pilot and Khartia’s chief technical consultant. The first Bumblebees were difficult to operate, but through cycles of feedback and updates they became better. “In the beginning it didn’t fly without a professional pilot,” he said. “Now it can fly with a newbie.” Serhii said he had tested 15 semiautonomous terminal-attack drones from different manufacturers, and Bumblebee was the best. A new generation of Bumblebees is in the works, he added, with a stronger airframe and night optics.

Hardware upgrades would be welcome. But the captain who integrates new tech into Khartia’s operations said hardware was not the secret ingredient behind Bumblebee’s performance. It is the firmware and the flight software, BeeQGroundControl, that separates the drone from others. “Eric Schmidt made a very innovative drone,” he said, adding that Bumblebee is one of the only drones in Ukraine that “is ready out of the box.” Teams simply add an explosive charge and begin work.

In one coordinated kamikaze attack, Serhii said, three Bumblebees and a standard F.P.V. drone destroyed a 152-millimeter howitzer inside Russia that was protected under a bunker roofed with logs. The first Bumblebee dove into camouflage netting and set it afire; the second breached the roof. Then the standard F.P.V. plunged inside and the final Bumblebee hovered overhead and scattered 10 small anti-personnel land mines around the site. The strikes were timed two minutes or less apart. Khartia has repeated the tactic. “There have been many similar attacks,” Serhii said.

Bumblebees are so valuable, he added, that teams flying them are assigned only to important missions — principally hunts behind Russian lines for artillery and logistics vehicles, and to carry relay transmitters that extend other drones’ ranges. Other units deliver packets of blood to bunkers that medics use to stabilize wounded soldiers awaiting evacuation, an officer supervising strike-drone teams said.

For all the ways that Bumblebees have brought together multiple autonomous features, Schmidt’s engineers, Ukrainians said, have not programmed weapons for full autonomy. Like NORDA Dynamics’s Underdog, Bumblebees require a human to designate targets before attack. “My opinion is that we need to leave the final judgment to the human being,” one Bumblebee test pilot said. Schmidt has agreed. “There’s always this worry about the ‘Dr. Strangelove’ situation, where you have an automatic weapon which makes the decision on its own,” he said in a televised 2024 appearance. “That would be terrible.”

Image

A soldier known by the call sign Lipa (left) from Ukraine’s Khartia Brigade, updating the software on Bumblebee attack drones.Credit...Finbarr O'Reilly for The New York Times

In “Dr. Strangelove,” the 1964 Stanley Kubrick movie, a Soviet doomsday device detects a rogue American attack and automatically launches a nuclear response, effectively exterminating humankind. Schmidt’s caution aligns with Pentagon policy, which embraces keeping “humans in the loop,” at least in an aspirational spirit. Its 2023 guidance for autonomy in weapons systems, known as Directive 3000.09, requires “appropriate levels of human judgment over the use of force,” and senior-level official review of all autonomous systems in development or to be deployed. But the directive offers no clarity about what, exactly, constitutes “appropriate levels of human judgment.”

Further, no global consensus or convention exists for these ideas or other forms of design constraint. The arms race is afoot without mutually accepted guardrails. Schmidt has prefaced his support for keeping people in the loop by pointing out that “Russia and China do not have this doctrine,” suggesting that weapons that kill outside of human supervision could find their way to the battlefield no matter anyone’s positions or desires.

At the Edge of Total Autonomy

The compete-or-die paradigm has brought semiautonomous weapons into new territory fast. X-Drone, for example, merges multiple forms of autonomous tech onto long-range drones. Its software helps navigate the weapons to a distant area, like a seaport, then uses computer vision to identify and attack specific targets — warships, fuel-storage tanks, parked aircraft. “You fly 500 kilometers and you miss a target by a little bit, and your mission is wasted,” the company’s founder said. “Now we train on an oil tank and it hits.”

Drones with X-Drone’s software have also hit trains carrying fuel and expensive Russian air-defense radar systems, clearing routes for more drones to follow, according to the founder. Andrii, a pilot of medium-range strike drones, said he flew more than 100 A.I.-enhanced missions in 2025 with the company’s software. His work involved flying to areas where reconnaissance flights detected a valuable target, then passing control to the software for terminal attack. On a sortie this fall, he said, the drone struck a mobile air-defense system.

By late 2025, the founder said, X-Drone had provided Ukrainian units with more than 30,000 A.I.-enhanced weapons. The company is experimenting with more complex capabilities, including loading facial recognition technology into drones that could identify then kill specific people, and coupling flight-control and navigation software with large language models, or L.L.M.s, “so the drone becomes an agent,” he said. “You can literally speak to the drone, like: ‘Fly to right, 100 meters. What do we see? Do you see a window? Fly inside the window.’”

Using armed quadcopters to peer into windows or enter structures is not new. The practice is common in shattered neighborhoods at the front. Videos posted on Telegram by Ukrainian units show piloted quadcopters performing exactly such feats, slipping into occupied buildings to kill Russian soldiers within. Adding a role for A.I. on such flights could allow this particular form of violence to expand.

With A.I.-enhanced weapons, the ethical distinction between two broadly different types of strike — a drone selecting a large inanimate object for attack and a drone autonomously hunting human beings — is large. But the technical difference is smaller, and X-Drone has already crept from the inanimate to the human. X-Drone has developed A.I.-enhanced quadcopters that, its founder says, can attack Russian soldiers with or without a human in the loop. He said the software allows remote human pilots to abort auto-selected attacks. But when communications fail, human control can become impossible. In those cases, he said, the drones could hunt alone. Whether this is occurring yet is not clear.

As semiautonomous weapons train to pursue people, Asaro, of the Stop Killer Robots Campaign, warned that entering this uncharted moral frontier was deeply worrisome, because computer programs applying rules to patterns of sensor data should not determine people’s fates. “These things are going to decide who lives and who dies without any sort of access to morality,” he said, and were the essence of digital dehumanization. “They are amoral. Machines cannot fathom the distinction between inanimate objects and people.” Ukrainians involved often agree. But whether fighting in brigades or coding in company offices, as members of a population unwillingly greased in blood, they speak of ample motivation to continue their work, and of little time for regret.

X-Drone’s founder had not intended to become an arms manufacturer; it is a role he neither sought nor foresaw. Born in Soviet Russia, he worked a long career in the United States and was arranging tech deals in Kyiv when the Kremlin’s forces invaded in 2022. A physicist by training, he joined a neighborhood defense unit, which gave him a rifle. When the Russian vanguard breached the capital near his home, he turned out to meet it, then recorded videos of the bloodied bodies of soldiers his group killed. Over a meal in Kyiv in 2025, he showed one of the videos almost incredulously. “All of my career I worked in Silicon Valley and on Wall Street,” he said, “and one day I am shooting Russians near my house?”

Now the front was only a few hours’ drive away, and Russia’s missiles and long-range drones could kill anyone in Ukraine in their sleep on any night. He nodded toward a peaceful daytime street scene. “It feels normal, but it’s just not,” he said. “This is an illusion of normality.”

Wars can push everyday people to extreme positions, which for a physicist can take the form of pragmatic epiphany: With Ukraine’s defenses slowly yielding ground, and defeat meaning a return to life under Moscow’s boot, developing A.I.-enhanced drones was logical, obvious and necessary. Western militaries were far behind, he said, and Ukraine’s resistance was buying them time. Its innovations might save them, too. “Drones with A.I. are the big game-changer,” he said. “The whole military infrastructure previously is obsolete.”

‘They Should Have Stopped the War Early On’

On the range where Pavlo trained pilots on Sine Engineering’s tech, one student, Yurii, who commands an F.P.V. platoon in a frontline brigade, brushed aside philosophical discussion. He had participated in some of the war’s most prominent battles, including the incursion in 2024 into Kursk. When the full invasion began, he was a medical doctor in Western Europe. Now he killed Russian soldiers, a career deviation he insisted contained no breach of his Hippocratic oath. While practicing medicine, he prescribed antibiotics to kill microbes to save patients and stop contagions’ spread. Strikes on Russian soldiers, he offered, amounted to a similar public service. “Now we are killing bugs, too,” he said. “They’re just larger bugs.”

A front-row participant in Ukraine’s adoption of drone warfare, Yurii had seen his share of new weapons. In his view, A.I.-powered drones were inevitable. “Any large-scale war, it delivers demons,” he said. “It unleashes something powerful and it accelerates developments which otherwise would have taken decades.” World War I saw rollouts of combat aviation, tanks and artillery, alongside widespread use of chlorine, phosgene and sulfur mustard. World War II ended after the United States destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki with nuclear bombs. “Who knows what this war is going to unleash,” Yurii said. “If the international community is concerned about this, then they should have stopped the war early on.”

Weapons as transformative as the combat drones proliferating in Ukraine are historically uncommon. They enforce tectonic shifts in military tactics, budgets, doctrines and cultures. Organizations that adapt to the new capabilities and dangers can thrive; those that do not suffer battlefield humiliations and miseries for their rank and file. The rapid evolution of drones, now accelerating through integration with autonomy, is a moment potentially analogous to the rise of the machine gun during the Russo-Japanese War.

That new weapon’s power was demonstrated during the 1904 siege of Port Arthur. Tsarist forces were thick with peasants and drunkards. Japan’s imperial ranks were motivated and well trained. But when they attacked fortified Russian positions in massed infantry assaults, they rushed into machine guns, previously unseen in state-on-state conventional war, that shattered their lines with sweeping bursts of fire. Western military attachés were present to observe events that darkened dirt red. And yet most nations failed to take notice. European armies, oblivious to what machine guns would mean for their soldiers’ fates, continued to feed cavalry horses and to preach the glories of the open-ground charge. A decade later, hapless generals poured away young lives on the Western Front, out of step with the technology of their time.

The state of Western military readiness today galvanizes Deborah Fairlamb, a founding partner of Green Flag Ventures, a Delaware-registered venture capital fund investing in Ukrainian defense-tech start-ups. Even before autonomous drones appeared, she said, the extraordinary proliferation of unmanned weapons outran nations’ defensive abilities. “Most people in the West do not understand what is happening here,” she said, and the gap could mean stinging defeat and enormous loss of life.

Image

The military section at Cemetery No. 18 in Kharkiv, one of many burial grounds for Ukrainian soldiers killed in its war with Russia.Credit...Finbarr O'Reilly for The New York Times

Fairlamb lives in Kyiv. Her alarm sounded after American veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq visited Ukraine to prospect for business or fight as volunteers. They entered a war in which new tech has caused almost unfathomable carnage. Russia and Ukraine have suffered well over a million combined casualties in less than four years, with most wounds caused by drones. “They come back from the front, like, shaken,” she said, and they share a refrain: “My team would not last for 48 hours out there.” With A.I.-enhanced drones joining the action, Fairlamb described the need to boost A.I.-arms development as no less than existential, prompting her to approach embassies and arms manufacturers with urgency. “It really and truly is about making people understand how dramatically different this technology is,” she said. “And how unbelievably unprepared the United States is.”

For Schmidt, multiple motivations appear to overlap. At Stanford in 2024, he said he entered drone manufacturing after seeing Russian tanks destroy apartments with elderly women and children inside. His entrance to the war earned him genuine gratitude from Ukrainians, whether they fly Bumblebees or are at decreased risk every time a Merops interceptor hits a Shahed. With a year-plus of combat shock-testing of its products, his operation is also well positioned for potential profits as nations reassess and update their arsenals in light of lessons learned from Ukraine.

He has framed his movement into the A.I. arms sector as implicitly humanitarian. “Now you sit there and you go, Why would a good liberal like me do that?” he said at Stanford. “The answer is that the whole theory of armies is tanks, artilleries and mortars, and we can eliminate all of them and we can make the penalty for invading a country, at least by land, essentially be impossible.” A.I.-powered weapons, he suggested, could end this kind of warfare.

This is a prediction with precedent from when machines guns were poised to upend ground combat as people knew it. In 1877, Richard Gatling, inventor of the Gatling gun, a prominent forerunner of automatic fire, proposed that as an efficient multiplier of lethal violence his weapon might spare people the horrors of war. “It occurred to me,” he wrote, that “if I could invent a machine — a gun — which could by rapidity of fire, enable one man to do as much battle duty as a hundred, that it would, to a great extent, supersede the necessity of large armies.”

Maybe the future will prove Eric Schmidt’s vision right. Whatever is coming will reveal itself in time. History shows Gatling was spectacularly wrong.

Yurii Shyvala contributed reporting.