- Lease Structure: Carnegie House operates as a ground-lease cooperative, meaning residents own building shares while leasing the underlying land from a separate entity.

- Cost Escalation: Ground rent for the property increased by 450 percent in 2025, rising from $4.36 million to $24 million based on fair-market land values.

- Equity Depletion: The drastic increase in operating costs has caused shareholder equity values to collapse and raised the risk of building dissolution.

- Risk Awareness: Purchasers in ground-lease buildings typically pay lower prices to compensate for the inherent risk that land values will appreciate faster than building values.

- Legislative Proposal: New York Senate Bill S2433 seeks to cap annual ground-rent increases at 3 percent or the Consumer Price Index for leases older than 30 years.

- Market Impact: Imposing rent caps on land may discourage investment, prevent property redevelopment to its highest use, and undermine the residential ground-lease market.

- Legal Constraints: Legislative interference with existing private contracts may violate the Contract Clause of the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits states from impairing contractual obligations.

- Economic Solution: Maintaining the integrity of property rights and expanding the overall housing supply are presented as the viable alternatives to government-mandated contract revisions.

[

Photo by Garrett Lawrence on Unsplash

For decades, residents of Carnegie House enjoyed what looked like a rare bargain at one of Manhattan’s most coveted intersections. Their apartments on 57th Street and Sixth Avenue sold at a steep discount to nearby market prices.

But like over 100 similarly situated “ground-lease” cooperatives across New York City, the low prices came with a catch. Carnegie House does not own the land on which it sits. Instead, its residents own shares in the building while leasing the land from a separate owner—a structure that keeps purchase prices low while shifting long-term risk onto buyers.

Yet Carnegie House’s ground lease recently renewed, and rent owed to the landowner skyrocketed. Shareholders saw their equity values collapse overnight. The co-op now faces the risk of dissolution, a move that would erase what remains of owners’ equity and turn them into rent-stabilized tenants.

The result has been litigation and calls for legislative intervention in Albany. But legislation that interferes with the rights and obligations of a ground lease would likely invite constitutional challenges and set a harmful precedent for property rights and urban land use, with consequences extending far beyond a single building.

Carnegie House’s ground lease has been the subject of concern for years. The lease, signed in 1959, set the building’s annual ground rent at 8.1667 percent of the fair-market value of the unencumbered land, with three 21-year renewal options. That structure worked reasonably well for decades. But when the lease renewed in 2025, soaring land values caused the ground rent to spike by 450 percent, from $4.36 million to $24 million, causing panic among residents.

A legal fight ensued. After an arbitration panel allowed the ground-rent hike to proceed, the co-op appealed the decision to a New York trial court. It lost, leaving residents uncertain about whether the building would default. If that happens, shareholders would see their equity wiped out while remaining responsible for any outstanding mortgage payments. The building itself would revert to rent-stabilized rentals, effectively ending the cooperative.

The vast majority of New York City’s co-op buildings own the land beneath them, so rising land prices translated into higher share prices. Carnegie House’s shares, by contrast, did not capture this appreciation, which is one reason they traded at lower prices.

That distinction matters. Real estate functions both as a consumable good and a store of value. Demand for a given unit depends largely on two factors: its location and its physical characteristics.

Sometimes a parcel becomes particularly valuable or worthless because of its proximity to a nearby attraction or hazard. Carnegie House, for example, happens to sit along what has become known as “Billionaires Row,” home to multiple ultra-luxury condo towers. Land next to a new power station or homeless shelter, by contrast, may fall in value.

Cities, after all, are labor markets. Land located near centers of productivity and opportunity tend to appreciate over the long run. Since the 1970s, Manhattan land values have risen steadily as the city’s jobs market and economy have grown.

A co-op share or a condo unit in a building that owns its underlying land allows residents to benefit from both proximity to a productive labor market as well as rising land values. But in a ground-lease building like Carnegie House, the landowner carries the risks and rewards associated with the local economy and surrounding area, for better or worse.

Carnegie House’s shareholders can’t plausibly claim they were unaware of the risks associated with a ground lease. Any lawyer seeking to avoid a malpractice claim would inform his client of these dangers. Mortgages for ground-lease co-ops are much harder to secure, and cash purchases are often the only way a buyer can acquire shares at all. These constraints exist because lenders understand that ground leases introduce significant uncertainty, especially as renewal dates approach. According to the landowners, more than 100 units in Carnegie House are held as investment properties—suggesting many buyers were speculating that the lease terms would be overridden or unenforced in some way.

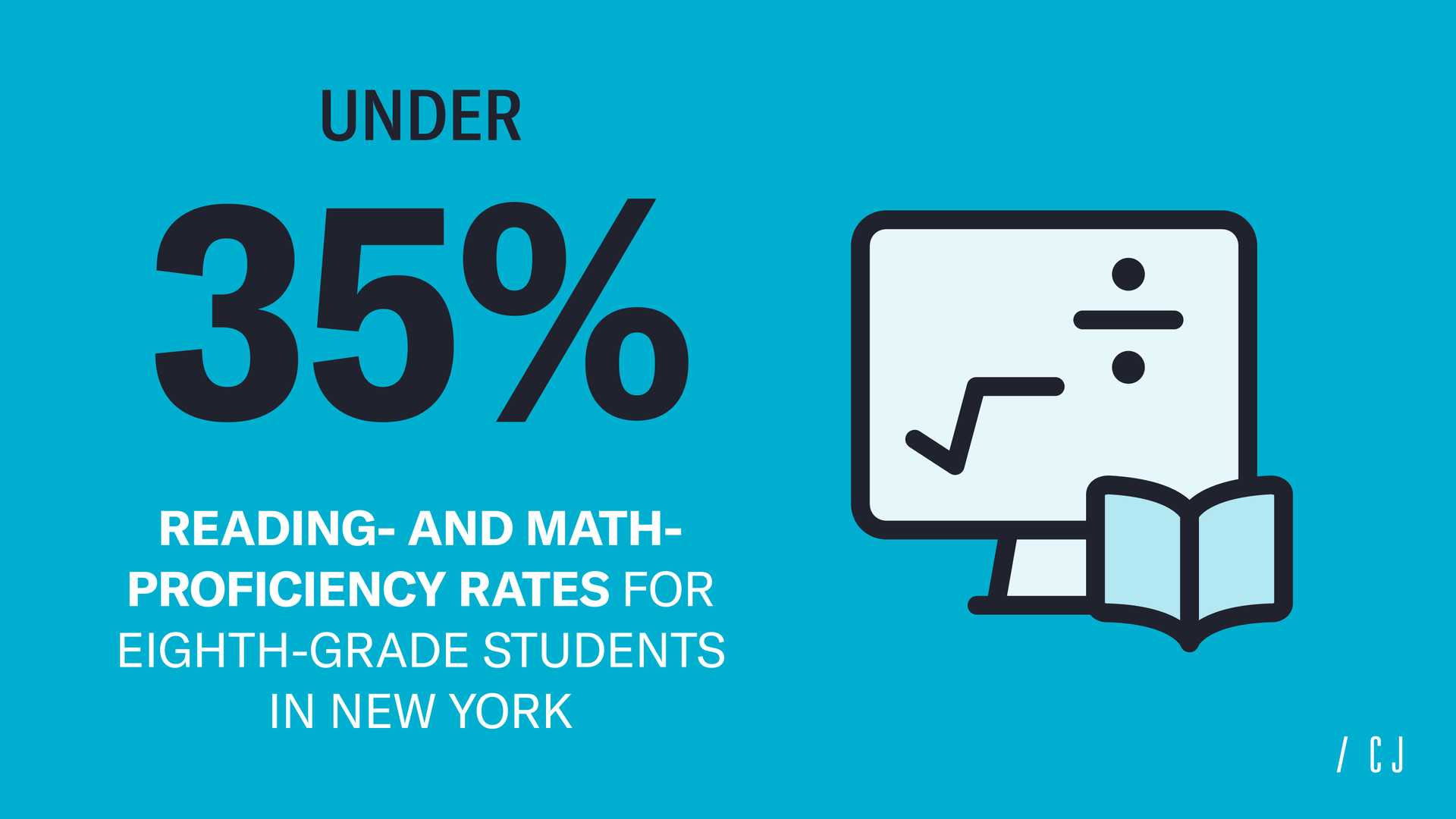

Unfortunately, some lawmakers in Albany are trying to give them the cover they were expecting. Senate Bill S2433 would cap annual ground-rent increases at 3 percent or the consumer price index, whichever is higher, for leases that are 30 years old or more. Capping increases in this way would effectively kill the market for residential ground leases and prevent land from being redeveloped to accommodate new circumstances.

Urban land should generally be free to be priced and redeveloped as circumstances change to achieve its highest and best use. Artificially suppressing ground rents would sever the link between land values and land use, discouraging redevelopment even when economic conditions warrant it. The destruction of the magnificent Gilded Age mansions that once lined Fifth Avenue along Central Park may be lamentable, but it was necessary to allow New York to grow—quite literally—to new heights.

S2433 would also grant co-op owners subject to a ground lease a right of first refusal if the landowner ever sought to sell the lease. Landowners would be required to disclose the price and material terms of any proposed sale and give the co-op up to 120 days to match the offer and purchase the land.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because the proposal nearly matches the Community Opportunity to Purchase Act (COPA), a New York City Council bill nearly passed last fall that would have given qualified nonprofit organizations the right of first refusal when certain residential buildings were put up for sale.

The bill would have introduced delay, uncertainty, and political considerations into ordinary property transactions, discouraging investment. After sustained criticism of the bill—especially in City Journal—COPA fell short of a veto-proof majority. Mayor Eric Adams vetoed the bill, and new City Council Speaker Julie Menin declined to revive it (at least for now).

Despite the harsh consequences for co-op owners, ground leases should be enforced as written, without legislative intervention. For one thing, a bill like S2433 risks violating the Constitution’s Contract Clause, which prohibits states from passing any law “impairing the Obligation of Contracts.”

And if a law like S2433 passes, it would fundamentally undermine the reliability of real property leaseholds. Carnegie House’s owners can’t plausibly claim not to have understood the risks; many bet that they’d get bailed out in some form. Many enjoyed living in a location coveted by billionaires at a relative bargain. The co-op’s board can attempt to purchase the land and charge shareholders a special assessment—as the owners of Trump Plaza did in 2015 without government intervention—but the price would likely be too steep for most Carnegie House owners to bear.

Sympathy for co-op owners caught in bad ground-lease deals is understandable. But legislative relief for Carnegie House would invite appeals from other investors who made bad—or at least risky—deals and now want Albany to rescue them from unfavorable outcomes. If these owners had more housing alternatives available to them, their predicament wouldn’t be quite as dire.

As Albany has proven time and again, measures like S2433 are likely to make a bad deal worse. The real solution lies not in rewriting contracts, but in expanding housing supply.

A demonstration organized by the Minnesota Immigrant Rights Action Committee. (Photo by: Michael Siluk/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

A demonstration organized by the Minnesota Immigrant Rights Action Committee. (Photo by: Michael Siluk/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Representative Kelly Morrison, Representative Ilhan Omar, and Representative Angie Craig. (Photo by Octavio JONES / AFP via Getty Images)

Representative Kelly Morrison, Representative Ilhan Omar, and Representative Angie Craig. (Photo by Octavio JONES / AFP via Getty Images)