Pfizer should have started its first analysis of its pivotal Covid vaccine trial nearly a month before Election Day 2020, confidential data from that trial show.

Like the news Pfizer put out on Nov. 9, 2020, six days after the presidential vote, the earlier analysis would have seemed to show the jab was effective enough to end the Covid epidemic — and likely powerfully helped Donald Trump against Joe Biden.

But Pfizer did not follow its own plans for the analysis, or a second analysis which would have been even stronger and also should have come out before the election. Instead, the company used a Food and Drug Administration demand for more safety data to slow-walk findings on the jab’s apparent effectiveness - and kneecap Trump.

Dr. Albert Bourla, Pfizer’s chief executive, gave the public false information on the trial’s status on Oct. 27, one week before Election Day, claiming Pfizer did not have enough data to know if the jab was working — when in reality it did.

Federal prosecutors in Manhattan and a House committee are now investigating Pfizer’s actions, following a tip from a rival drug company. What they find may be unpleasant for Pfizer and Bourla.

—

(The truths about Pfizer and the rest of the medical-industrial complex - with your help.)

Subscribe now

—

Why didn’t Pfizer follow its own schedule and put out the trial results as soon as possible — giving billions of people around the globe hope that the epidemic would be over soon, instead of delaying?

In response to complaints from Trump at the time, Pfizer executives insisted their political views played no role. But after Donald Trump left office, Bourla did not hide his disdain. Bourla referred to Trump, though not by name, as an “agent of evil.”

In a 2022 speech, Bourla said:

When people use disinformation to create fear, they become agents of evil… [such as during] the January 6th attack on the U.S. Capitol, when lies and conspiracy theories threatened the peaceful transfer of power and resulted in the death of five police officers… History is rife with illustrations of the high cost of disinformation – of the harm that can be inflicted when people in positions of power knowingly lie.

By then, Pfizer had become a close partner of the Biden Administration, which spent tens of billions of dollars in taxpayer dollars to buy its mRNA jabs. In a February 2021 trip to a Pfizer manufacturing plant, Biden lavished praise on Bourla and the company.

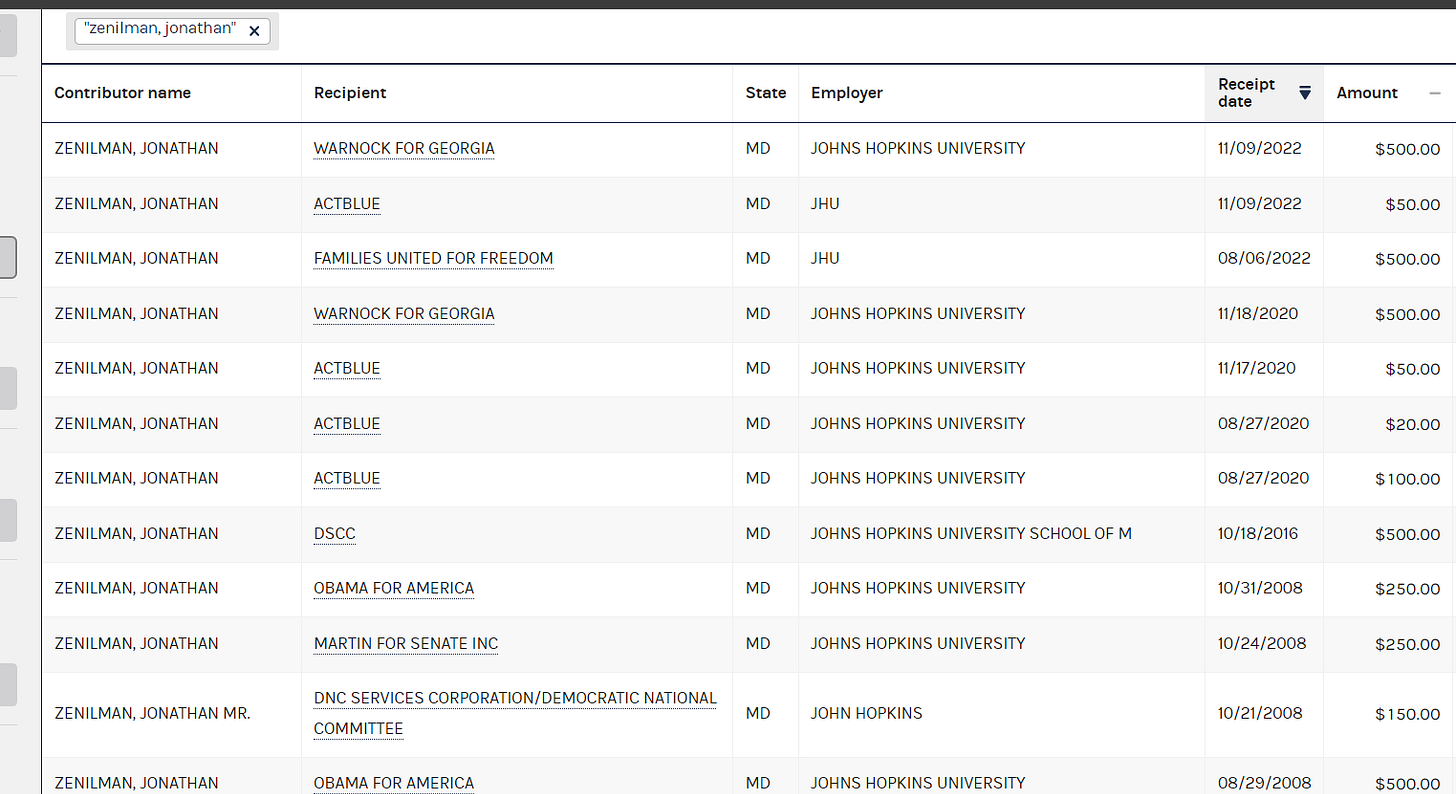

In addition, Dr. Jonathan Zenilman, a physician at Johns Hopkins whom Pfizer had hired to run the nominally independent “data monitoring committee” that could see the trial results early, openly despised Trump and gave to the Democratic lobbying group ActBlue repeatedly in 2020.

(Neither Pfizer nor Zenilman nor any of the other members of the Data Monitoring Committee responded to emails requesting comment for this article. I am suing Bourla and Dr. Scott Gottlieb, a Pfizer board member, for their roles in forcing Twitter to censor me in 2021. )

—

(Follow the science. And the donations.)

—

Federal prosecutors in Manhattan and a Congressional committee are now investigating if Pfizer sat on the trial results, according to the Wall Street Journal. (Pfizer’s corporate partner in the vaccine was BioNTech, a German company that actually developed the mRNA technology used in the shot. But Pfizer ran the trial, managed the results, hired Zenilman and the data monitoring committee and provided the committee with information, and decided when the results would be released. No one has suggested BioNTech played any role in delaying the results.)

In a March 2025 article, the Journal reported GlaxoSmithKline, a British drug company, had told prosecutors that a former Pfizer vaccine scientist had told Glaxo executives that Pfizer delayed its positive report.

The Journal downplayed the allegation, saying “there has never been evidence to support the accusation.”

In fact, the truth — as is so often the case — has been hiding in plain sight for years.

It can be seen in a statement the scientist, Phil Dormitzer, gave to the Journal for its March piece: “My Pfizer colleagues and I did everything we could to get the FDA’s Emergency Use Authorization at the very first possible moment.”

Dormitzer is not lying. The key words in his statement are “Emergency Use Authorization.”

—

Throughout August and September 2020, Pfizer and its partner BioNTech had predicted trial results — and possibly even regulatory approval that would enable people to receive shots — for their Covid vaccine in October. “From my perspective, October,” Bourla had said on Aug. 9. “We will know if it works… We would go for regulatory approval in October.”

At the time, Pfizer and its rivals with promising vaccines were in an all-out race to enroll patients in clinical trials. Executives and investors knew the first drugmaker to announce an apparently successful Covid jab would reap huge financial and reputational rewards as the company that ended the epidemic.

Pfizer and Moderna, the two companies testing mRNA vaccines, were ahead of their competitors. Pfizer had a slight lead over Moderna because Moderna had to slow enrollment in its trial in early September slightly to find more non-white patients. Still, the two companies were neck-and-neck. Whatever animus for Trump Bourla might have felt in summer was subsumed to Pfizer’s desire to win the race for the first successful shot.

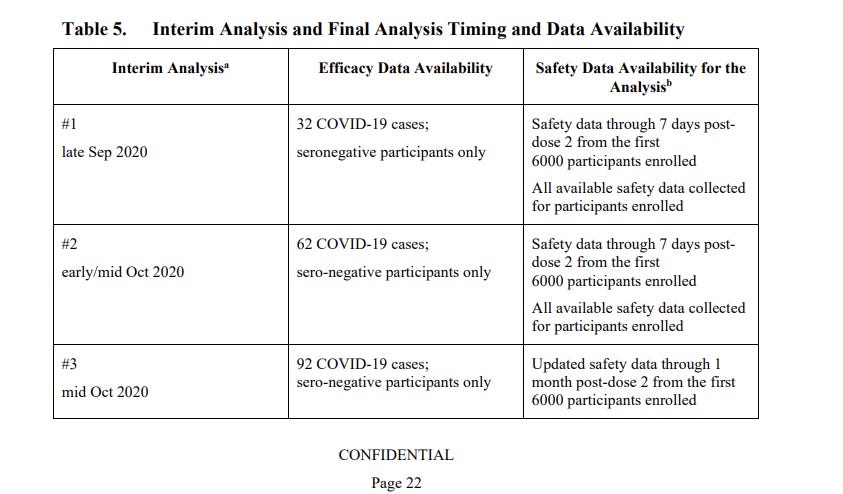

So in June 2020, before the most critical portion of the trial even started, Pfizer and BioNTech had changed the trial’s guidelines to allow for several early peeks at their data, called “interim analyses.” The first would occur when 32 patients became sick with Covid.

The independent “data monitoring committee” which Zenilman headed would then learn which of the 32 Covid patients had received Pfizer’s vaccine and which had gotten placebo shots. Depending on the breakdown, the committee could let the trial continue to accumulate more data, stop it because the shot was working so well, or stop it because the vaccine didn’t seem to work at all.

—

(Pfizer’s internal timeline, per a presentation it made to Australian regulators on Sept. 18, 2020. It predicted the first internal analysis as early as late September.)

SOURCE

—

Then two things happened.

First, the timeline slipped slightly from Pfizer’s late-September prediction, because people in the trial got Covid more slowly than expected. Pfizer would later tell the public that the reason for the slip was that Covid became less common in September and October, before suddenly accelerating again in late October — a handy excuse for the delay.

This was largely untrue.

In reality, cases continued to accumulate fairly steadily throughout October, though they picked up a bit as more and more people reached the period a week beyond their second dose that made them eligible to be counted.

Instead, the timeline slipped because the vaccine was working too well. Essentially no one who received a second dose of mRNA became infected with Covid during September and October. Almost all the cases came from the placebo arm, slowing the moment at which the 32-case switch (and later switches) would be hit.

Then, on Oct. 6, 2020, FDA officials posted guidelines demanding a longer period of safety data before Pfizer or other vaccine companies could apply for an EUA, which would make the shots available to the public.

As everyone involved with the vaccine trials knew, the FDA’s new stance would make authorizing, much less distributing, a vaccine impossible before the election — no matter how good the effectiveness data looked.

—

That decision was out of Pfizer’s control.

But though it could not apply for authorization until mid-November, when it would have the safety data the FDA wanted, Pfizer could still announce whether the vaccine worked to prevent infection on its own schedule — based on the trial data.

As the reaction to the Nov. 9 announcement proved, effectiveness was what really mattered to the public; most people were happy to assume the shots were safe.

Bourla himself clearly explained this distinction in an “open letter” on Oct. 15, 2020, in which he still held out a possible October announcement:

We may know whether or not our vaccine is effective by the end of October. To do so, we must accumulate a certain number of COVID-19 cases in our trial to compare the effectiveness of the vaccine in vaccinated individuals to those who received a placebo. Since we must wait for a certain number of cases to occur, this data may come earlier or later based on changes in the infection rates. As Pfizer is blinded to who received the vaccine versus the placebo, a committee of independent scientists will review the complete data and they will inform us if the vaccine is effective or not based on predetermined criteria at key interim analysis points throughout the trial…

In the spirit of candor, we will share any conclusive readout (positive or negative) with the public as soon as practical, usually a few days after the independent scientists notify us.

A key point that I’d like to make clear is that effectiveness… alone, would not be enough for us to apply for approval for public use. [emphasis added]

—

Bourla’s statement wasn’t wrong.

Except.

By the time he made it, the trial had already accumulated 32 Covid cases, the number that should have caused the data monitoring committee to run its first interim analysis on the vaccine’s effectiveness.

That analysis — stunningly — would have shown that the Pfizer jab approached complete protection beginning seven days after its second dose, the date at which the shots were considered fully effective.

Of the first 32 Covid infections in people in the trial who had received their second dose more than a week before, not one occurred in people who had received Pfizer’s mRNA product. All 32 occurred in people who received placebo. The odds of that outcome happening by chance were less than 1 in 4 billion — far less than the odds of winning Powerball.

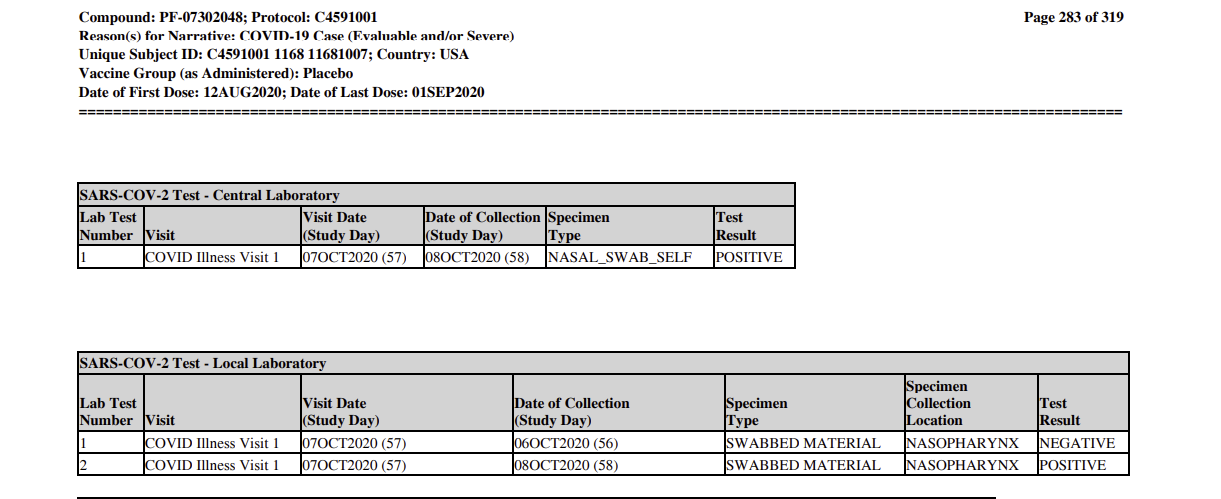

We know when the trial reached that milestone from Pfizer’s own submission of the trial data to the FDA. Pfizer never expected those documents to become public, but the FDA released them in response to a lawsuit. They contain detailed data on every case of Covid that occurred in a trial subject, including the exact date a nasal swab was taken from a patient with a suspected case of Covid for confirmation at a “central laboratory.”

According to the documents, the 32nd positive Covid nasal swab was taken on Oct. 8 -a day when several new positive cases emerged. Though the processing time to deliver and test the swabs isn’t specified, commercial Covid test processing routinely occurred within 24 hours by the fall of 2020.

—

(The 32nd swab, give or take. Note the date of collection.)

SOURCE

—

Yet Pfizer and the independent data monitoring committee which Zenilman headed never ran that first interim analysis.

This omission is particularly interesting because by early October, even the blinded data the company had seen would have suggested strongly the vaccine was working.

The reason is that infections did occur with some frequency after the first shot in both the placebo and vaccine groups. Those cases were not counted for the trial analysis but that the company knew were occurring. The slowdown in cases that occurred after the second shot could only have been read as strong protection from the vaccine.

Further, the trial was not entirely blinded within Pfizer. A handful of Pfizer employees had access to the unblinded data throughout the trial. That visibility was largely a safety precaution, in case the shots caused “antibody dependent enhancement” and worsened cases of severe Covid. In fact, though, the severe Covid cases also mostly occurred in the placebo arm, as the unblinded Pfizer employees knew.

—

So when did Zenilman and the data monitoring committee — and Bourla and Pfizer —learn that the 32-case switch had been reached? They have never said.

Further, the charter creating the committee does not set precise rules for how or how quickly Pfizer had to notify Zenilman that the case threshold had been reached, or how quickly he had to respond so the company could begin the process of unblinding the data.

Instead, the charter explains that meetings “may occur weekly and DMC [data monitoring committee] members will be expected to convene at short notice due to the accelerated pace and critical need of the study if required,” then adds “the frequency of meetings will be dependent upon availability and nature of data to be reviewed and will be agreed between Pfizer and the Chair [Zenilman].”

In other words, although the charter anticipated the committee would want to review and unblind the trial data essentially immediately, it did not require Zenilman to do so. He and Pfizer had considerable discretion over when to begin an unblinded analysis.

—

What Bourla and other executives have said is that after the FDA announced its Oct. 6 guidelines, the company began to talk to the agency about skipping the first interim analysis and instead running the analysis when 62 cases were reached, supposedly as a way to have more data and a more statistically powerful analysis.

On Oct. 29, Pfizer formally confirmed that change by updating the trial’s “protocol,” the detailed document that explained exactly how it would conduct the trial.

“For operational reasons, removed the interim analysis planned after accrual of 32 cases,” the updated protocol explained.

Instead, the analysis would begin when 62 Covid infections had been reported to the company, the company said.

—

There was only one problem. The trial reports that Pfizer provided to the FDA show the 62nd — not the 32nd, the 62nd — positive swab was taken from a patient on Oct. 21, 2020.

At that point, 61 of the 62 positive cases had occurred in people who received the placebo, with just one in the vaccine arm. Those results were even more powerful than the 32-case analysis would have been.

But the company did not start analyzing cases for the data monitoring committee on Oct. 21 or 22. That timeline almost certainly would have led to the results being released at the end of October at the latest — several days before Nov. 3, Election Day. Instead, Pfizer continued to wait.

In fact, Pfizer ensured it wouldn’t have good news to report before Election Day by failing to start the 62-case interim analysis until after it had changed the protocol. And it apparently went even further.

At some point in October, they even stopped testing the nasal swabs they’d received from Covid patients, as William Gruber, Pfizer’s senior vice president of vaccine clinical research and development, explained on Nov. 9, 2020, to a drug industry newsletter:

Gruber said that Pfizer and BioNTech had decided in late October that they wanted to drop the 32-case interim analysis. At that time, the companies decided to stop having their lab confirm cases of Covid-19 in the study, instead leaving samples in storage. The FDA was aware of this decision.

Two days later, an article in Science magazine claiming that “No evidence supports Trump's claim that COVID-19 vaccine result was suppressed to sway election” offered a slightly different timeline:

On 3 November, FDA approved the protocol changes and the companies assumed the trial was crossing the 62-case mark. It then took several days to check the stored samples—and they also had new ones coming in that they could test, too. Combined, these samples led to the 94 cases presented to the DMC on 8 November.

But neither the timeline Gruber offered nor the timeline in Science are accurate, at least not according to the documents Pfizer later provided to the FDA.

It appears that Pfizer, with Zenilman’s approval, simply refused to conduct the 32-case analysis in early-to-mid October — and then realized by the third week in October that it had an even bigger problem, that it was about to hit the 62-case threshold and needed to find a way to delay that analysis for an extra few days too. The “negotiations” with the FDA provided the excuse.

—

(I’ll never stop. All I need is your help.)

Subscribe now

—

But Pfizer and Bourla went out of their way in October and November to obfuscate this timeline. And at least once, Bourla appears to have gone further and said something demonstrably untrue.

On Oct. 27, in response to a question from a Wall Street analyst, Bourla said the clinical trial had not yet accumulated 32 infections — the moment at which the company was supposed to take its first peek at when the vaccine might work.

After some back-and-forth, an analyst cut to the chase:

Albert, with all due respect, could you please be absolutely clear whether the 32 events have been reached already? It seems that the answer is yes, Pfizer has the 32 events, otherwise I think you would say no…

Bourla was equally direct:

I will tell you clearly, no, we don't have the 32 events right now. So that's what I can say.

—

“So that’s what I can say.”

But Bourla wasn’t telling the truth.

Not even close.

Pfizer publicly reported the trial’s results on the morning of Monday, November 9th, to worldwide acclaim.

Among the people congratulating the company and its scientists that day was President-elect Joe Biden. In a statement on “Pfizer’s Vaccine Progress,” Biden praised “the brilliant women and men who helped produce this breakthrough and to give [sic] us such cause for hope.”

Just in time, too.

What do you think? Post a comment.