- Groundhog Project: The author introduces an open-source agentic coding tool named “groundhog” designed to teach how Cursor and similar coding assistants function.

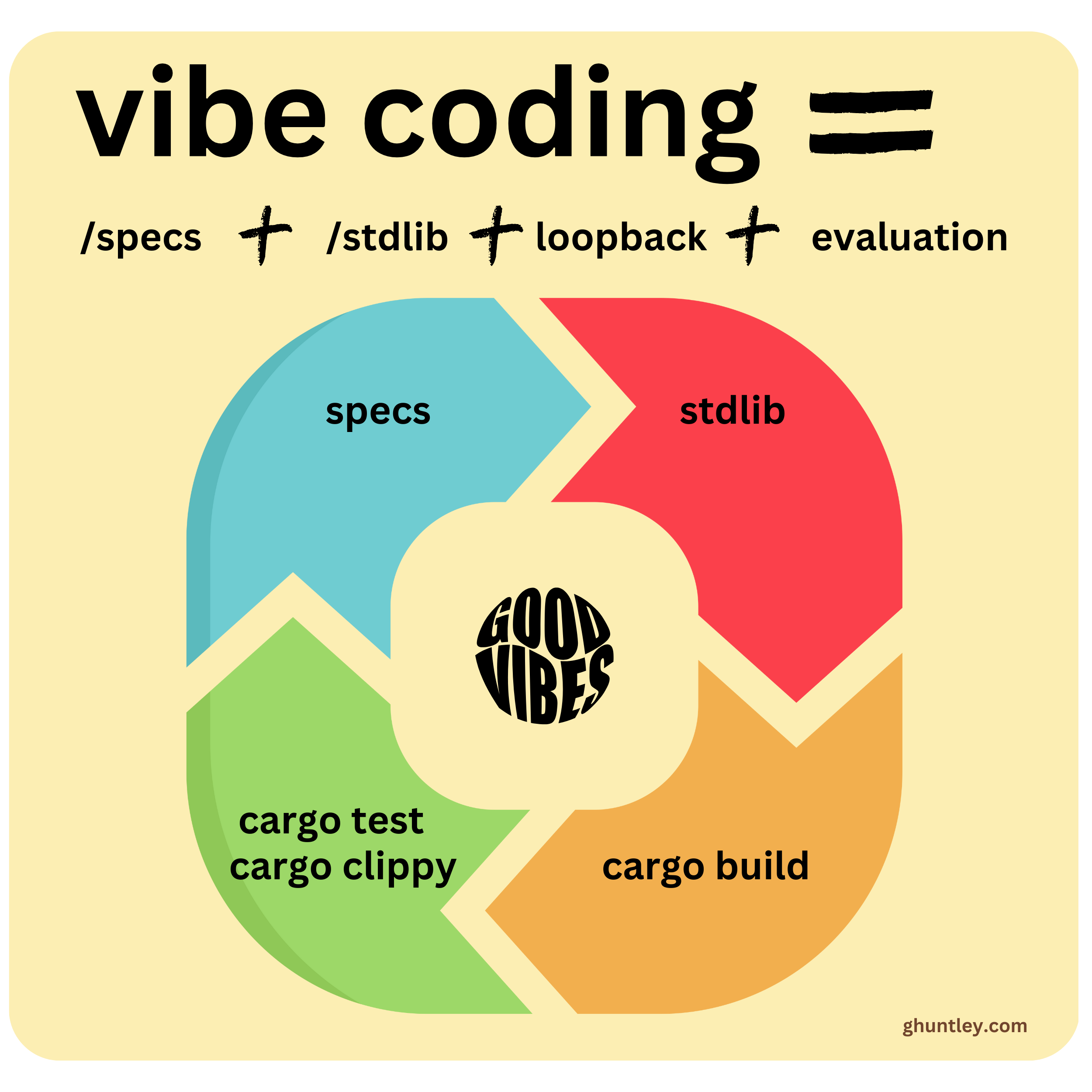

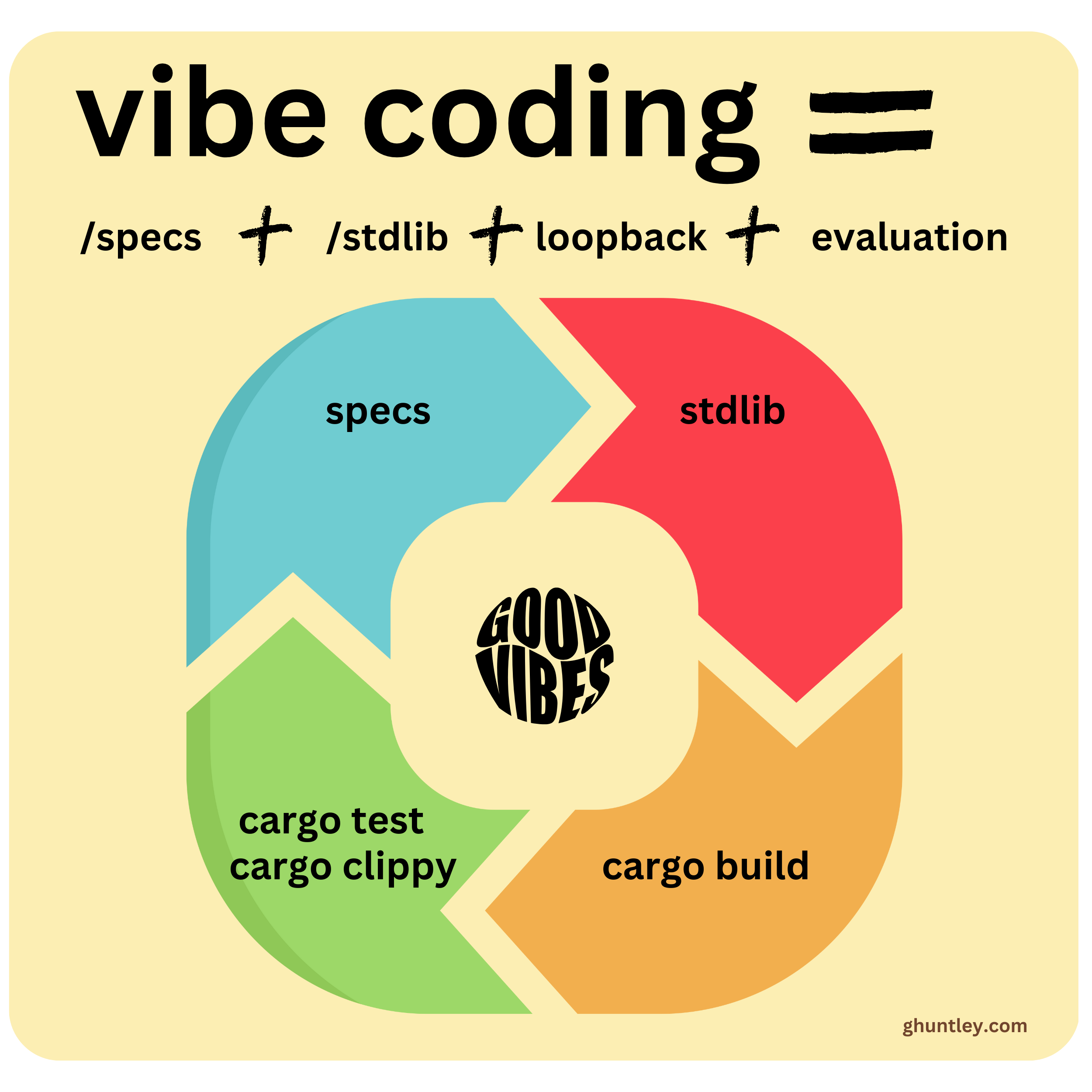

- Cursor Techniques: Combining the /specs method with stdlib rules and compiler-rich languages enables rapid, hands-free development by directing LLMs through detailed specifications.

- Specification Domains: The workflow segments the codebase into domains like src/core, src/ai/mcp_tools, and src/ui, letting multiple Cursor sessions work in parallel without overlap.

- Stdlib Automation: Cursor rules automate processes such as rule generation, git commits, and enforcing coding conventions for languages like Rust.

- Loopback Workflow: A core prompt loop instructs Cursor to study specifications and rules, implement missing functionality, add tests, and run builds and linting until completion.

- Multi-Boxing Strategy: Independent Cursor instances with separate git worktrees enable concurrent progress across different parts of the project.

- Recommendation of Languages and Tests: Rust or Haskell are preferred thanks to strong compiler guarantees and clear errors, paired with property-based tests or static analysis for quality feedback.

- Future Vision: The goal is to bootstrap Groundhog to self-build, with future posts covering MCP tools and links to the project repository plus social sharing options.

Ello everyone, in the "Yes, Claude Code can decompile itself. Here's the source code" blog post, I teased about a new meta when using Cursor. This post is a follow-up to the post below.

[

You are using Cursor AI incorrectly...

I’m hesitant to give this advice away for free, but I’m gonna push past it and share it anyway. You’re using Cursor incorrectly. Over the last few weeks I’ve been doing /zooms with software engineers - from entry level, to staff level and all the way up to principal level.

Geoffrey HuntleyGeoffrey Huntley

Geoffrey HuntleyGeoffrey Huntley

](https://ghuntley.com/stdlib/)

When you use "/specs" (this post) method with the "stdlib" (above) method in conjunction with a programming language that provides compiler soundness (driven by good types) and compiler errors, the results are incredible. You can drive hands-free output of N factor (entire weeks' worth) of co-workers in hours.

Today, alongside with teaching you the technique I'm announcing the start of a new open-source (yes, I'm doing this as pure OSS and not my usual proprietary licensing) AI headless agentic coding agent called "groundhog".

Groundhog's primary purpose is to teach people how Cursor and all these other coding agents work under the hood. If you understand how these coding assistants work from first principles, then you can drive these tools harder (or perhaps make your own!).

We'll be building it together, increment by increment, as a series of blog posts, so don't rush to GitHub and raise GitHub issues that XYZ does not work as I'm yet to decide on the community model around the project and doing customer support for free is not high up on my list.

[

GitHub - ghuntley/groundhog: Groundhog’s primary purpose is to teach people how Cursor and all these other coding agents work under the hood. If you understand how these coding assistants work from first principles, then you can drive these tools harder (or perhaps make your own!).

Groundhog's primary purpose is to teach people how Cursor and all these other coding agents work under the hood. If you understand how these coding assistants work from first principles, then y…

GitHubghuntley

GitHubghuntley

](https://github.com/ghuntley/groundhog?ref=ghuntley.com)

Groundhog is a teaching tool first. If you want a full-blown thing right now, go check out "Goose", "Roo/Cline", "Aider" or "AllHands".

All the code you are about to see was generated using these two techniques in conjunction with multiple concurrent sessions of the Cursor IDE open working on their own separate specification domain.

what the heck is a specification domain?

Consider a standard application layout on a filesystem:

src/core - this is where your core application lives.src/ai/mcp_tools - here is where your MCP tools live.src/ui - here is where your UI lives.

By driving the LLM to implement the core basics in a single implementation session before src/ai/mcp_tools and src/src/ui to build the "heart of the application", you can then fan out and launch multiple copies of Cursor to work on parts of the application that do not overlap.

[

Multi Boxing LLMs

Been doing heaps of thinking about how software is made after https://ghuntley.com/oh-fuck and the current design/UX approach by vendors of software assistants. IDEs since 1983 have been designed around an experience of a single plane of glass. Restricted by what an engineer can see on their

Geoffrey HuntleyGeoffrey Huntley

Geoffrey HuntleyGeoffrey Huntley

](https://ghuntley.com/multi-boxing)

Using https://git-scm.com/docs/git-worktree is a key ingredient to get it to work if you use a single machine, as you want each Cursor ("agent") to have its own working directory.

Start by authoring a "stdlib" rule to automatically do git commits as increments of the specification as it is also key. If you want to Rolls-Royce it, you can create a rule to auto-create a pull request when the agent is complete.

Now, you might be wondering about how to handle merge conflicts. Well, you can author a "stdlib" rule that drives Cursor to automatically reconcile the branches.

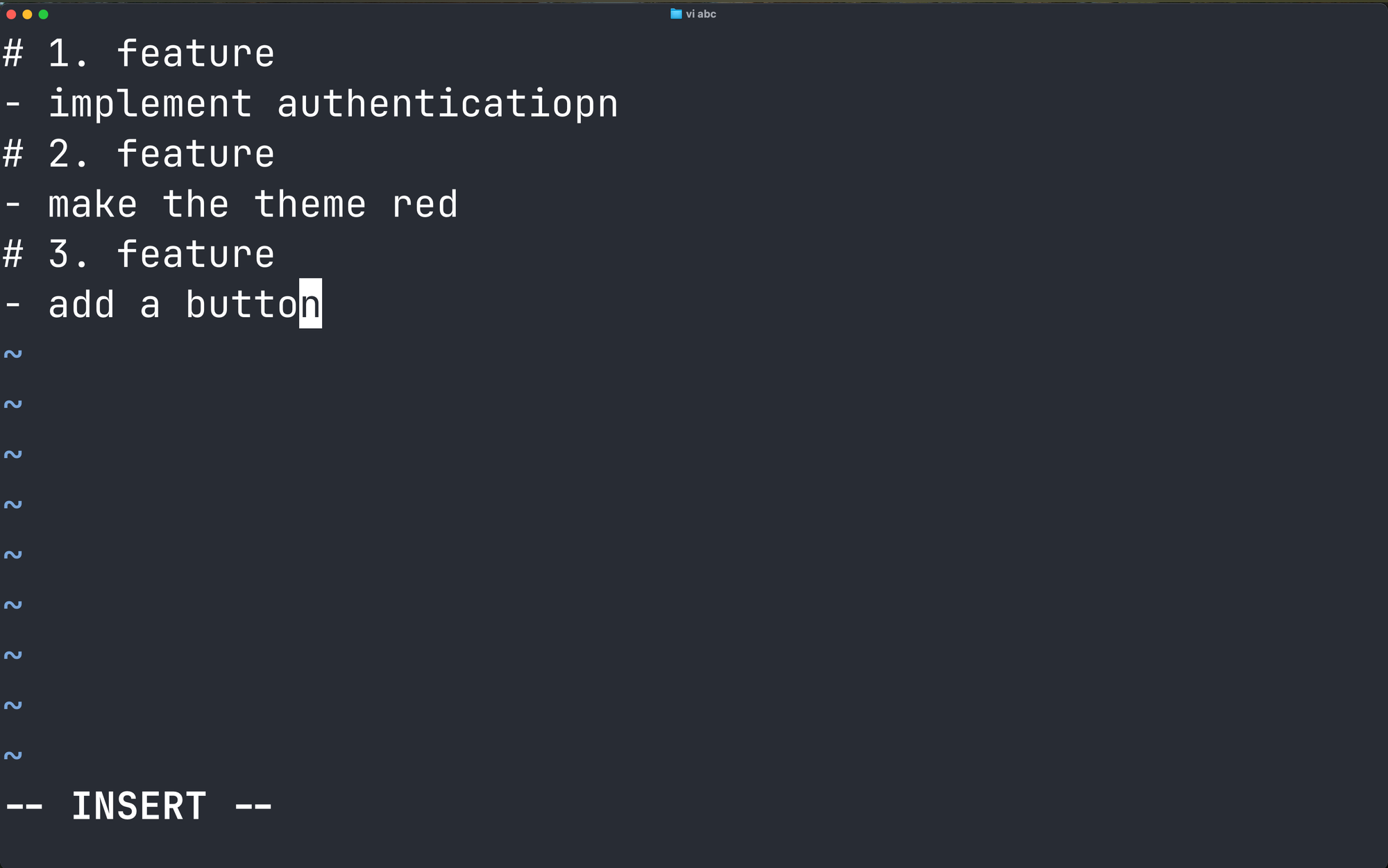

okay, what is a specification?

Specifications are the heart of your application; the internal implementation of an application matters less now. As long as your tests pass and the LLM implements the technical steering lessons defined in your "stdlib", then that's all that matters.

I'll be the first one to admit it's a little unsettling to see the API internals of your application wildly evolve at a rapid rate. Software engineers have been taught to control the computer; letting go and building trust in the process will take some time.

how I build applications now

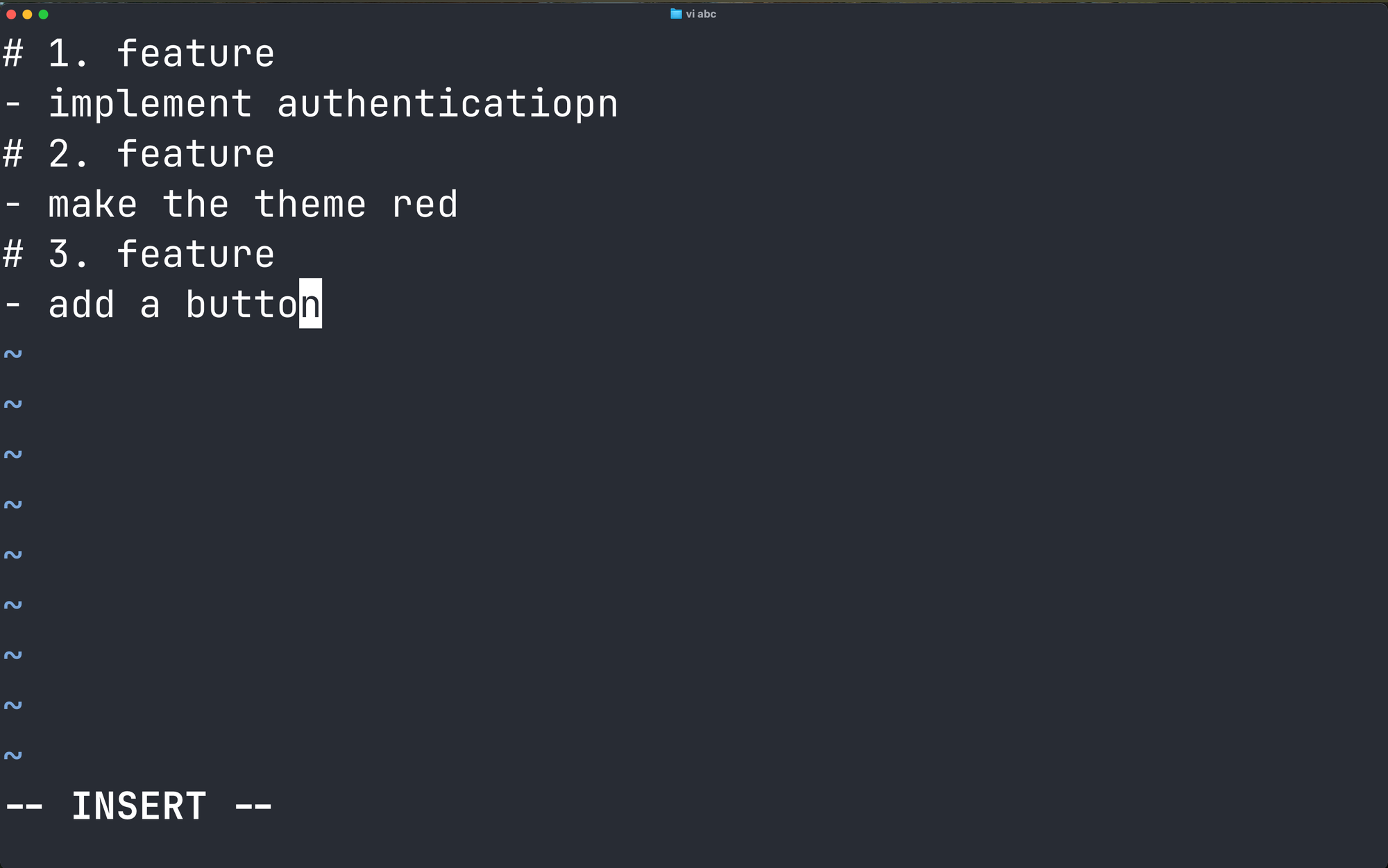

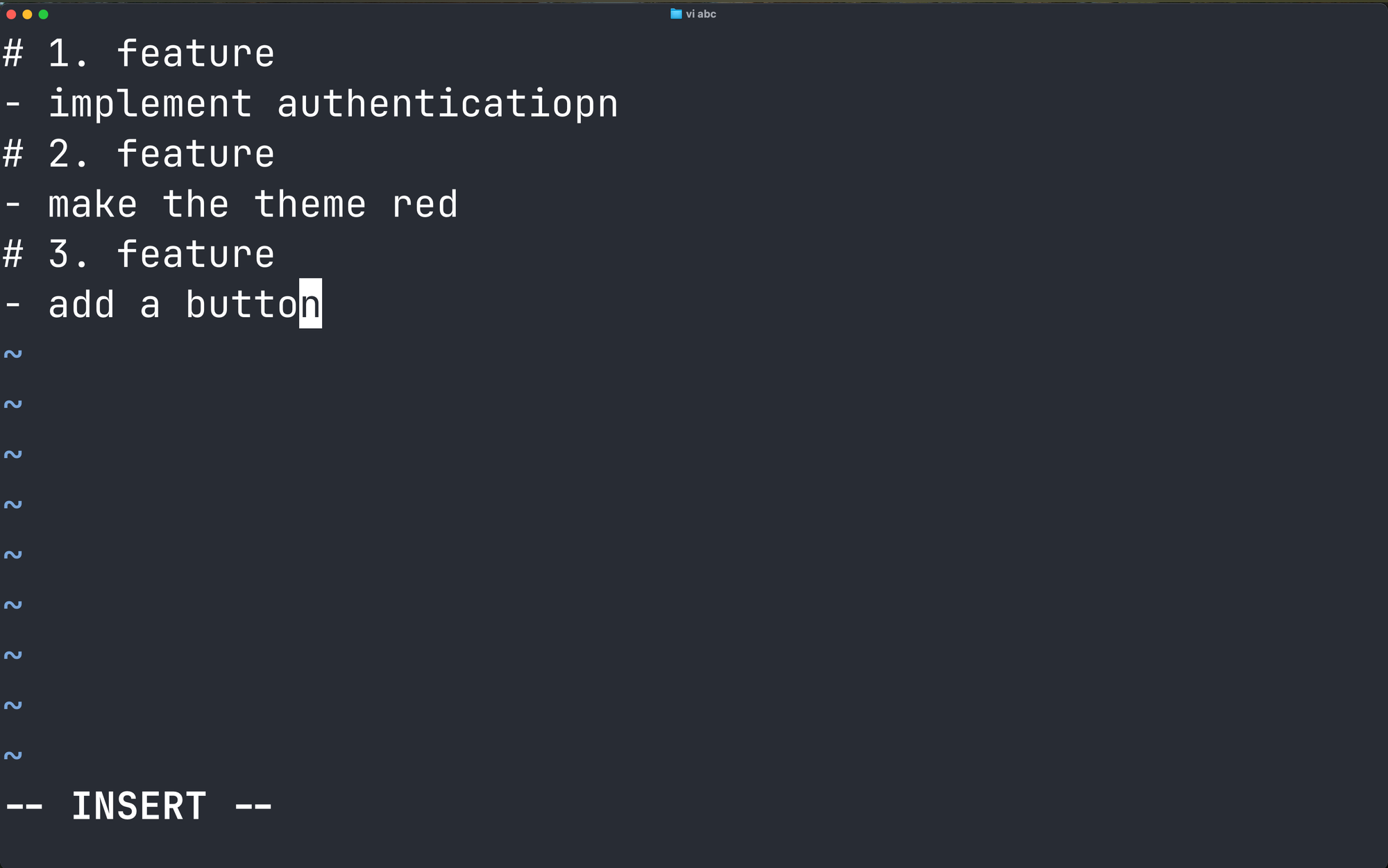

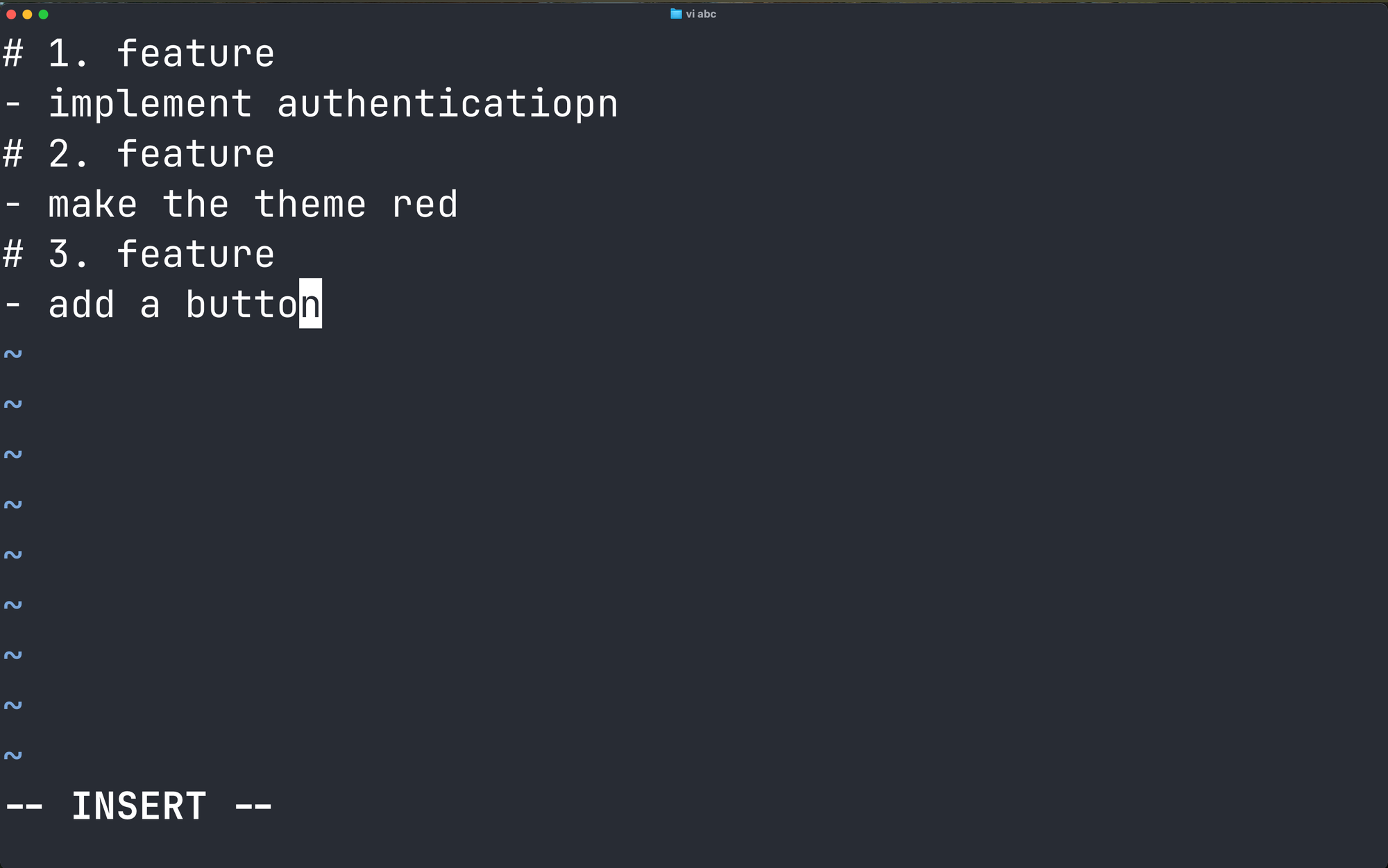

I start with a long conversation with the LLM about my product requirements aka specifications. For Groundhog, these are the prompts that I used

We are going to create an AI coding assistant command line application in rust

The AI coding assistant is called "groundhog".

It uses the "tracing" crate for logging, metrics and telemetry.

All operations have appropriate tracing on them that can be used to troubleshoot the application.

Use the clap cargo create for command line parsing.

The first operation is

"$ groundhogexplain"

When groundhog explain is invoked it prints hello world.

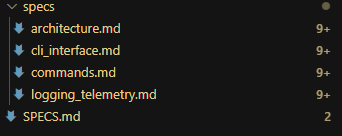

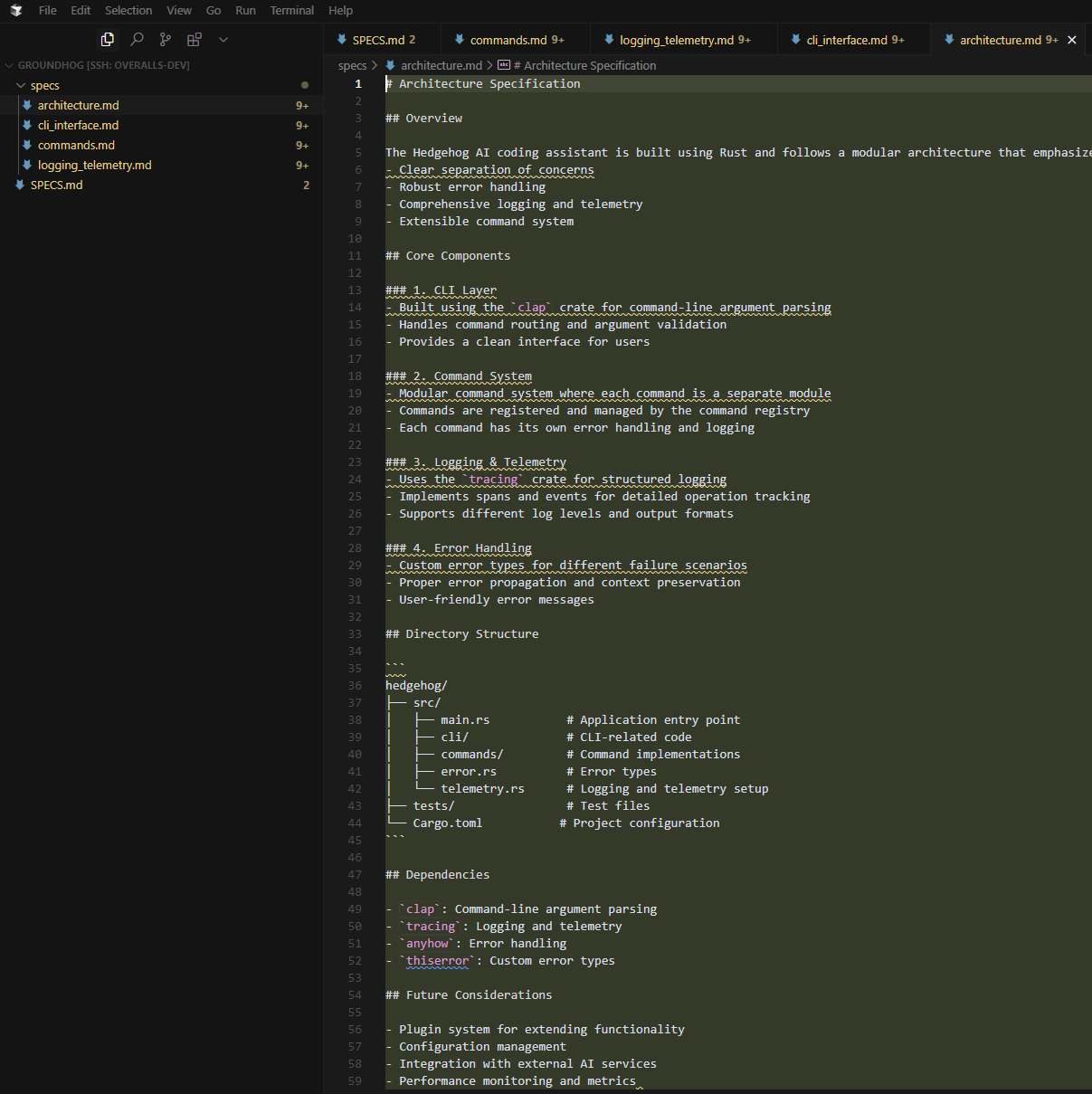

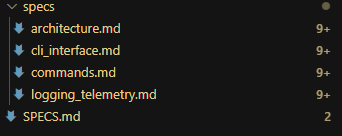

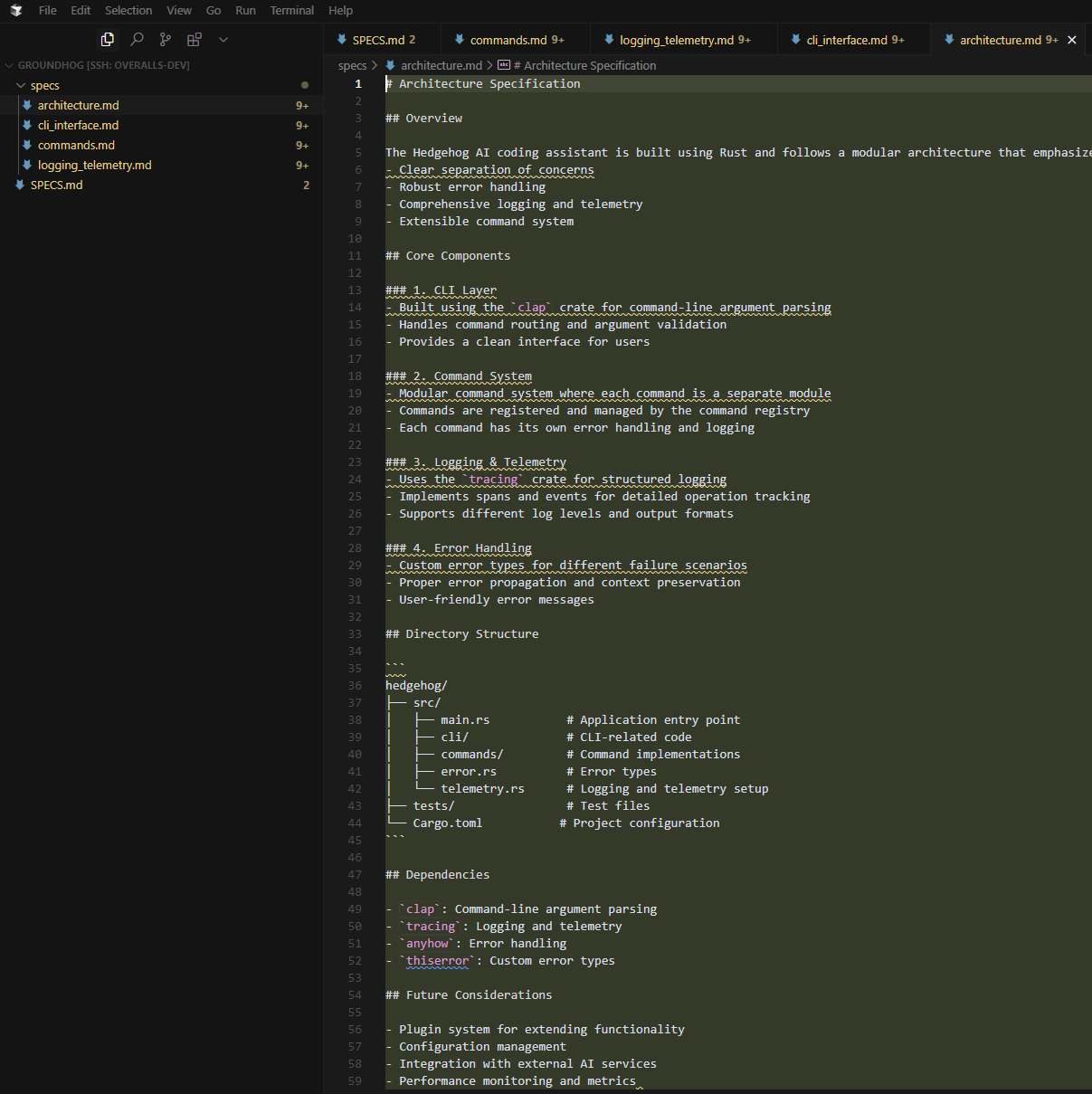

IMPORTANT: Write up the specifications into the "specs/" folder with each domain topic (including technical topic) as a seperate markdown file. Create a "SPECS.md" in the root of the directory which is an overview document that contains a table that links to all the specs.

After a couple moments something like this will be generated.

It's at this stage you have a decision to make. You can either manually update each file or keep on prompting the LLM to update the specification library. Let's give it a go.

Keep doing that until you are comfortable with the minimum viable product or increment of the application. Don't over-complicate it at first. Once you have the specification nailed, it's time to bring the "stdlib" into play. Let's build it up from first principles...

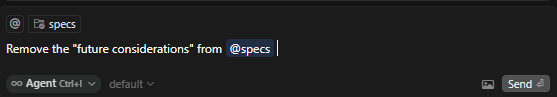

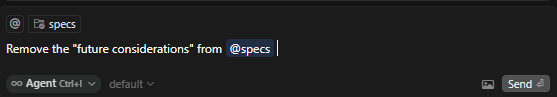

Create a Cursor IDE AI MDC rule in ".cursor/rules" which instructs Cursor to always create new MDC rules in that folder. Each rule should be a seperate file.

nice

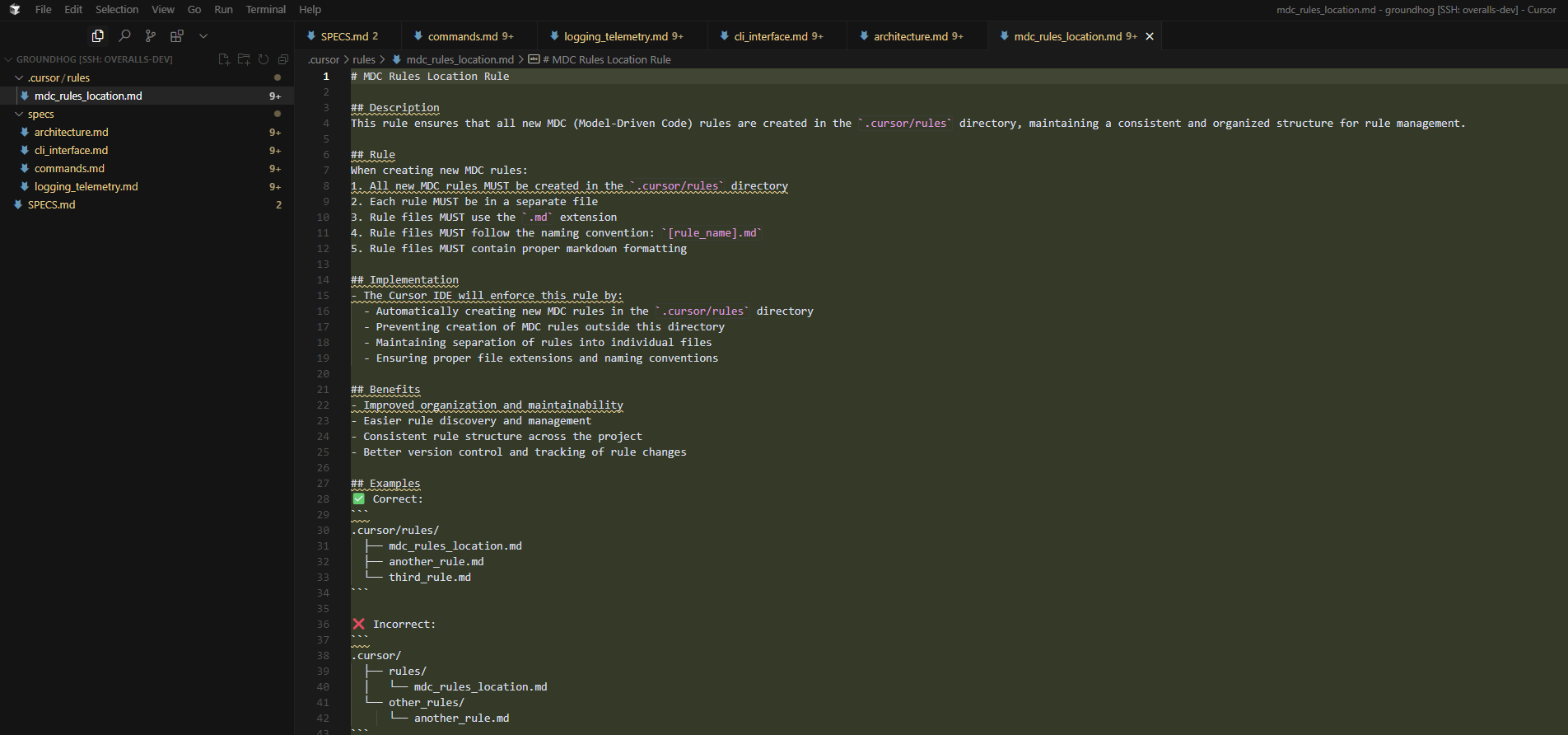

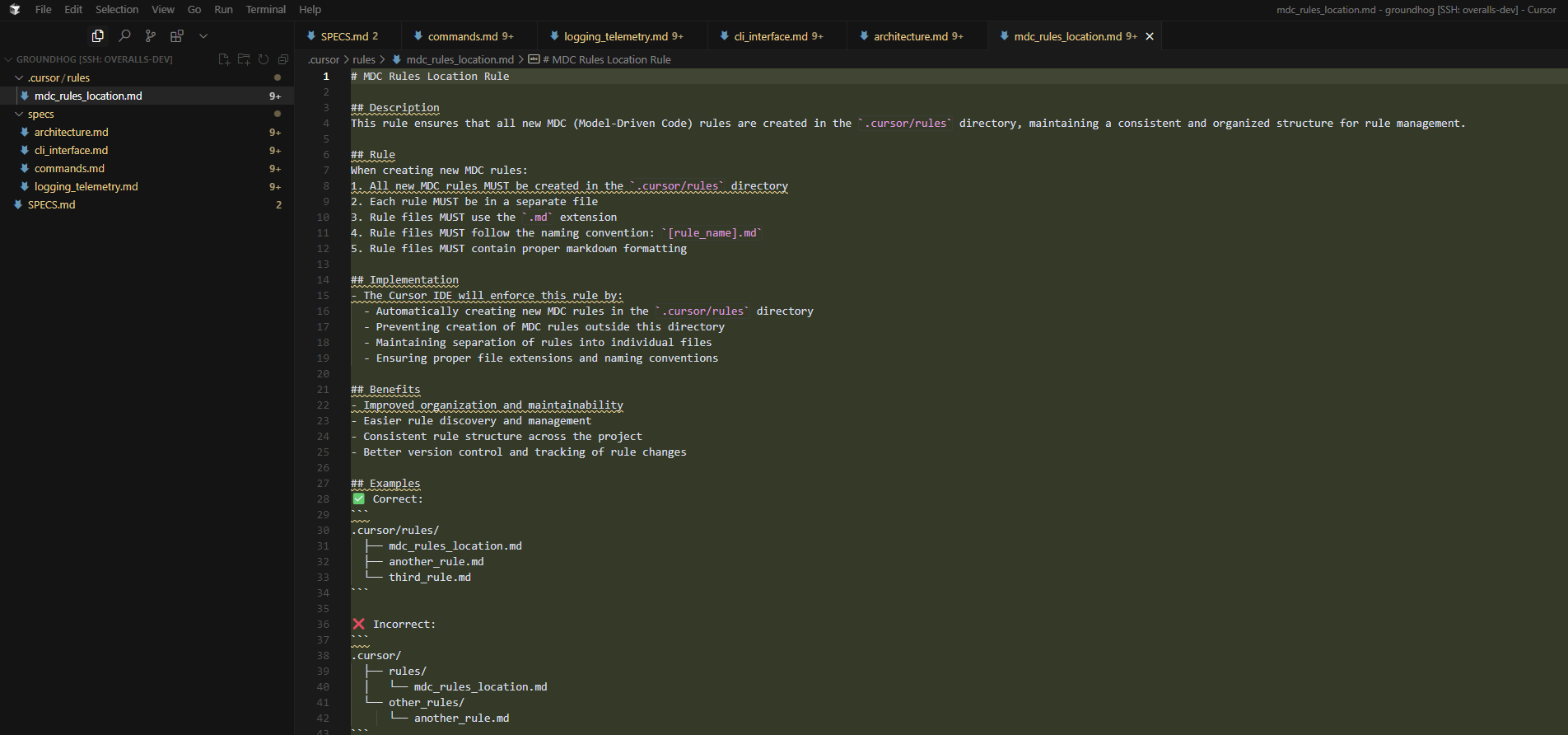

Nice. Okay, we have the first foundational rule. It's time to create some more, such as automating the git commits.

New Cursor IDE MDC rule.

After each change performed by Cursor automatically from Git commit.

Commit the changed files.

Use the "conventional git commit convention" for the title of the commit message

Explain what was changed and why the files were changed from exploring the prompts used to generate the commit.

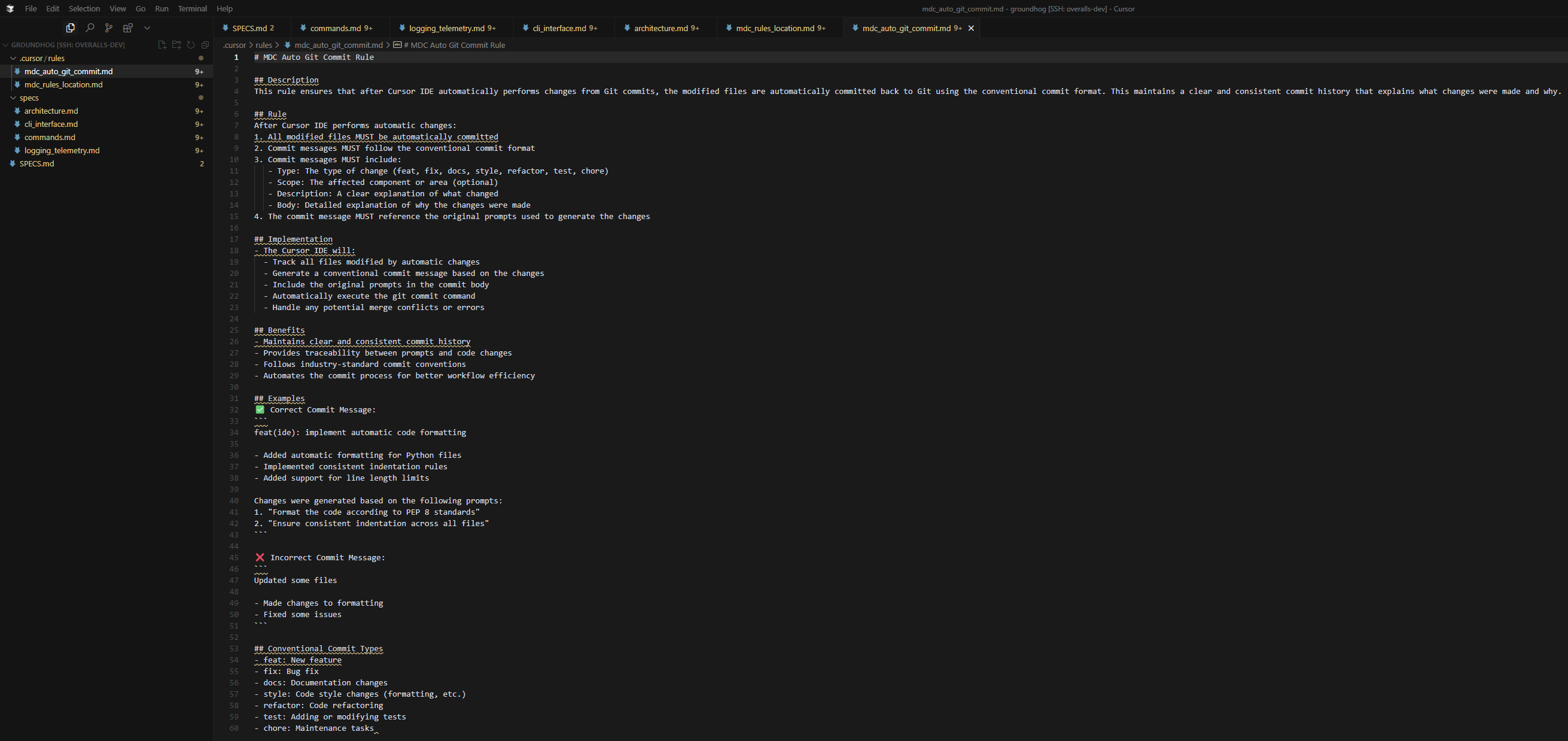

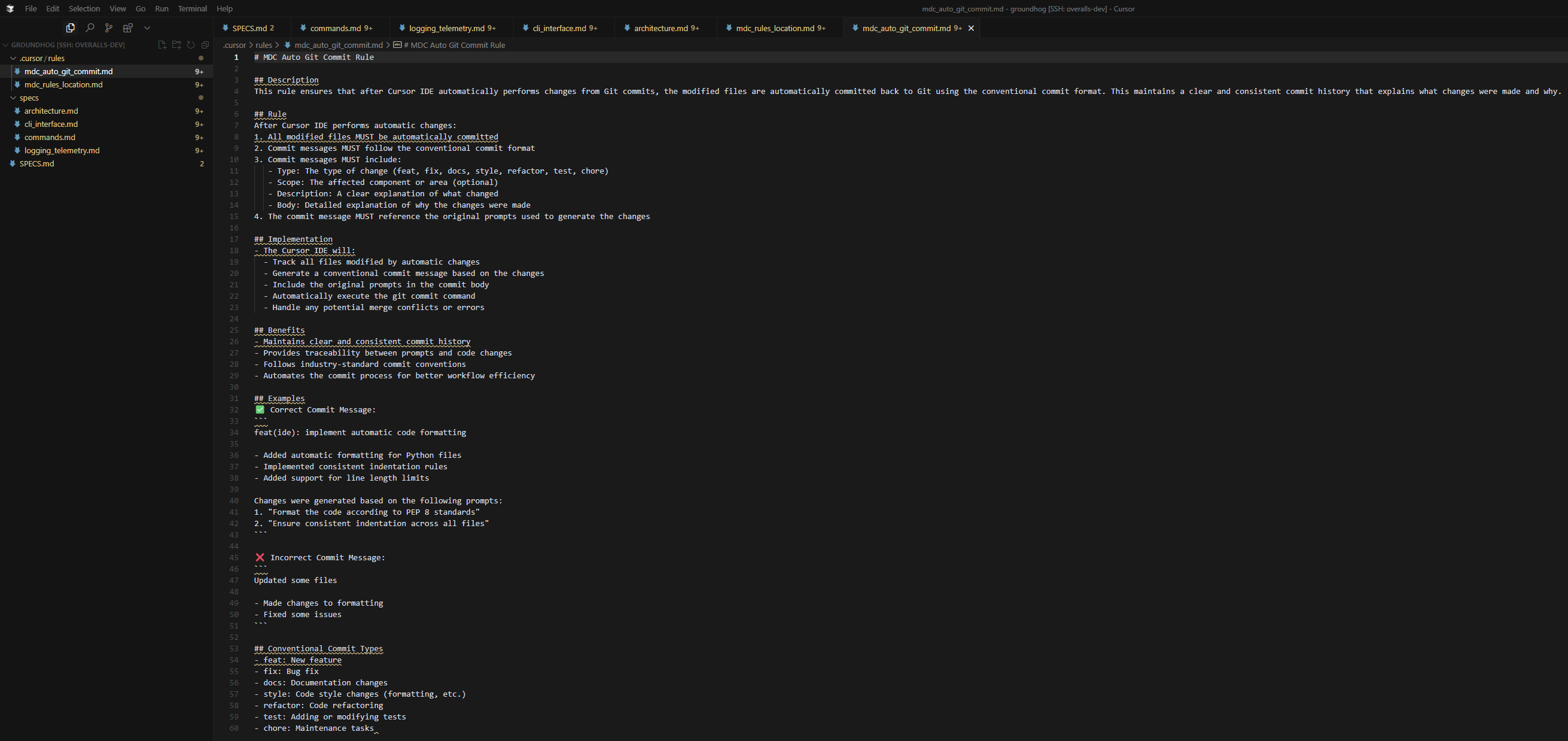

Okay, cool, now we are cooking with gas. The next step is to create a cursor rule that defines your coding conventions. As Groundhog is authored in Rust, let's generate best practices and save that as a rule.

Create a new Cursor MDC rule for all *.rs files (in all subdirectories)

You are an expert expert software engineer who knows rust. Infact you are the software engineer who created rust. Your task is to come up with technical recommendations in this rule which document best practices when authoring rust.

Split each concern about rust into seperate MDC rules.

Prefix each rule with the filename of "rust-$rulename.mdc"

Write these rules to disk

It's at this point, after these rules are generated, that you want to push the LLM harder. Ask it to continue...

After a few more rounds of this, manually review your new Cursor rules that instruct the LLM what you expect as technical output. If you want to speed run this then loop the new rules back onto the LLM.

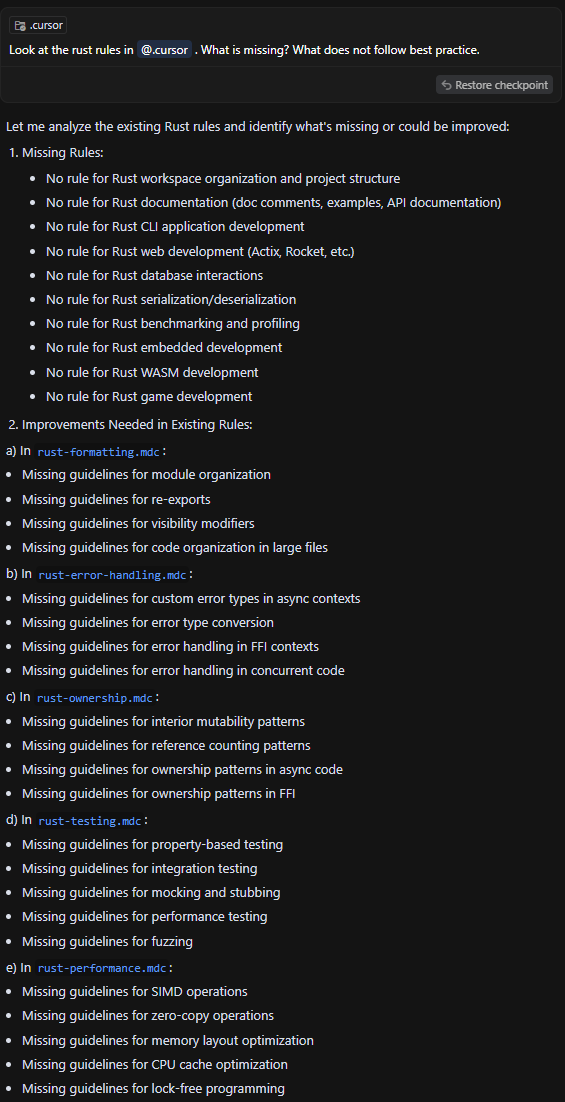

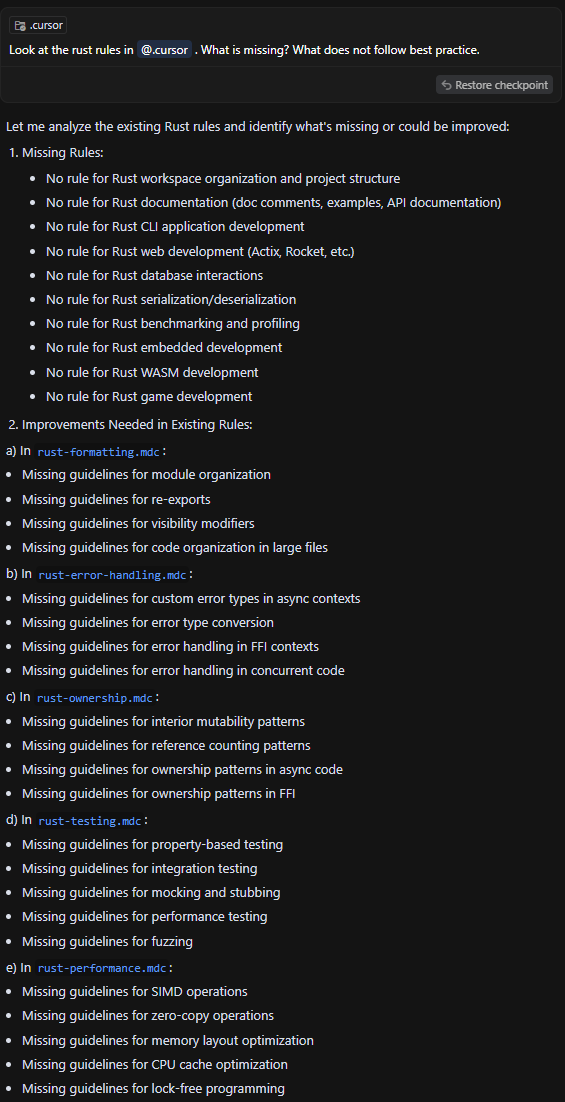

Look at the rust rules in @.cursor . What is missing? What does not follow best practice.

Notice how we looped the LLM back onto itself up there? It's the key LLM prompt you'll be using in conjunction with your newly formed spec and tech library going forward.

loopback is the key workflow

The secret to hands-free vibe coding is really just this prompt when used in conjunction with stdlib and specs library...

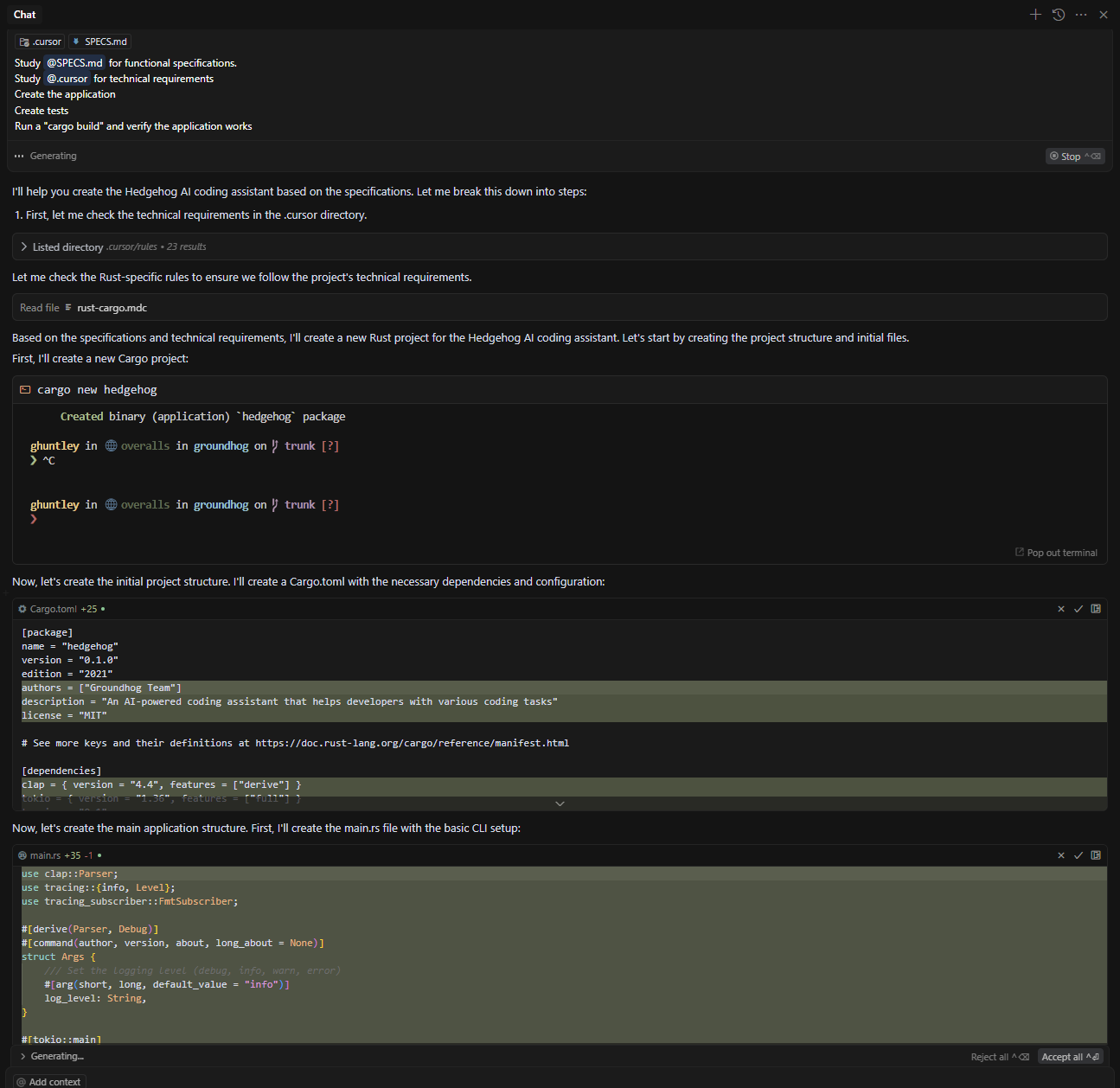

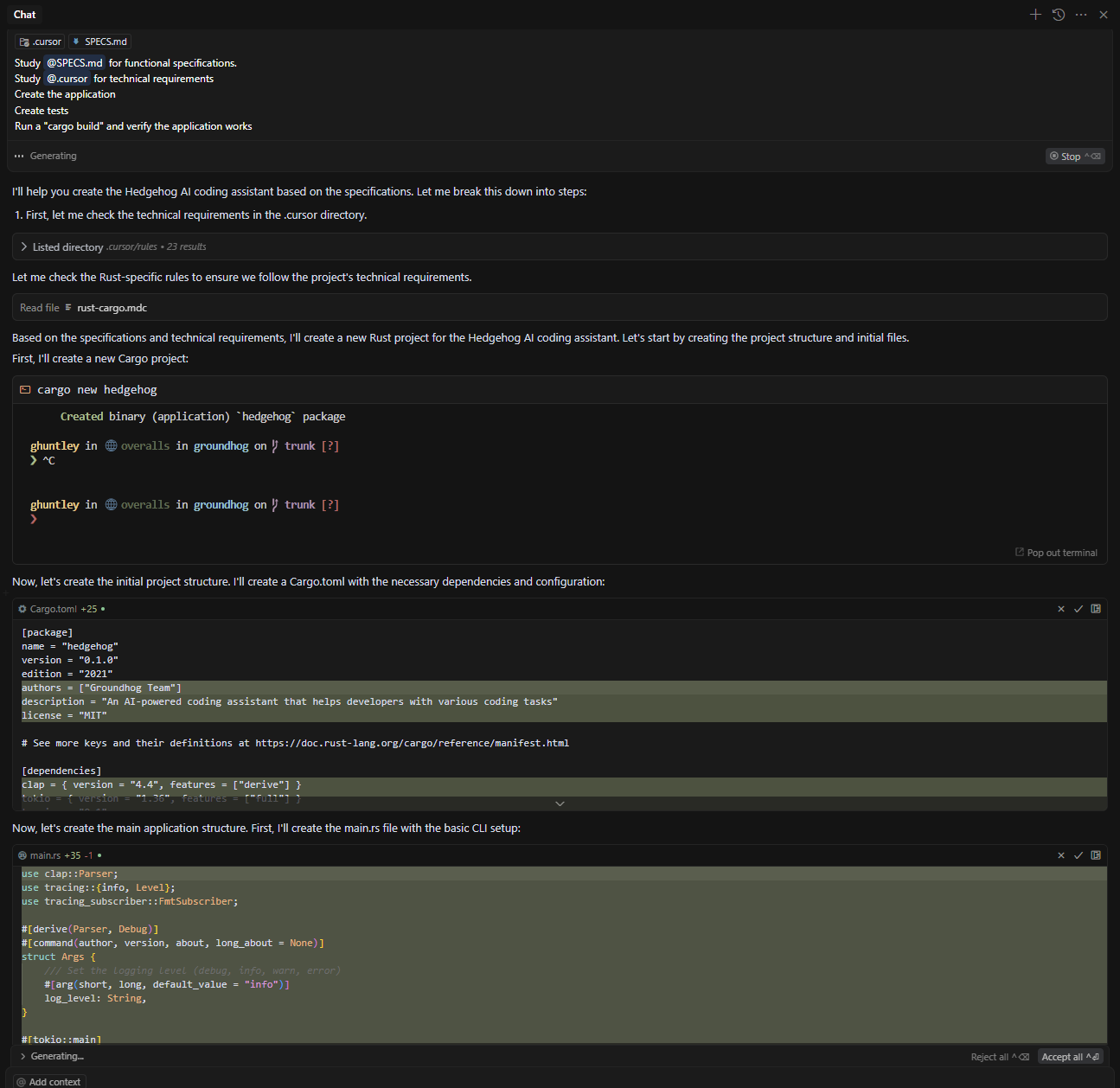

Study @SPECS.md for functional specifications.

Study @.cursor for technical requirements

Implement what is not implemented

Create tests

Run a "cargo build" and verify the application works

after a few moments, Groundhog will be generated. Cursor will time out or run out of tool calls during this operation

keep going until implemented

The next secret is really just continually issuing the same prompt

Study @SPECS.md for functional specifications.

Study @.cursor for technical requirements

Implement what is not implemented

Create tests

Run "cargo build" and verify the application works

Run "cargo clippy" and resolve linting errors

Did the LLM go on a bad path? Restart a new chat session to clear the LLM context window and use the above prompt. Keep doing it until everything is implemented.

scaling it up

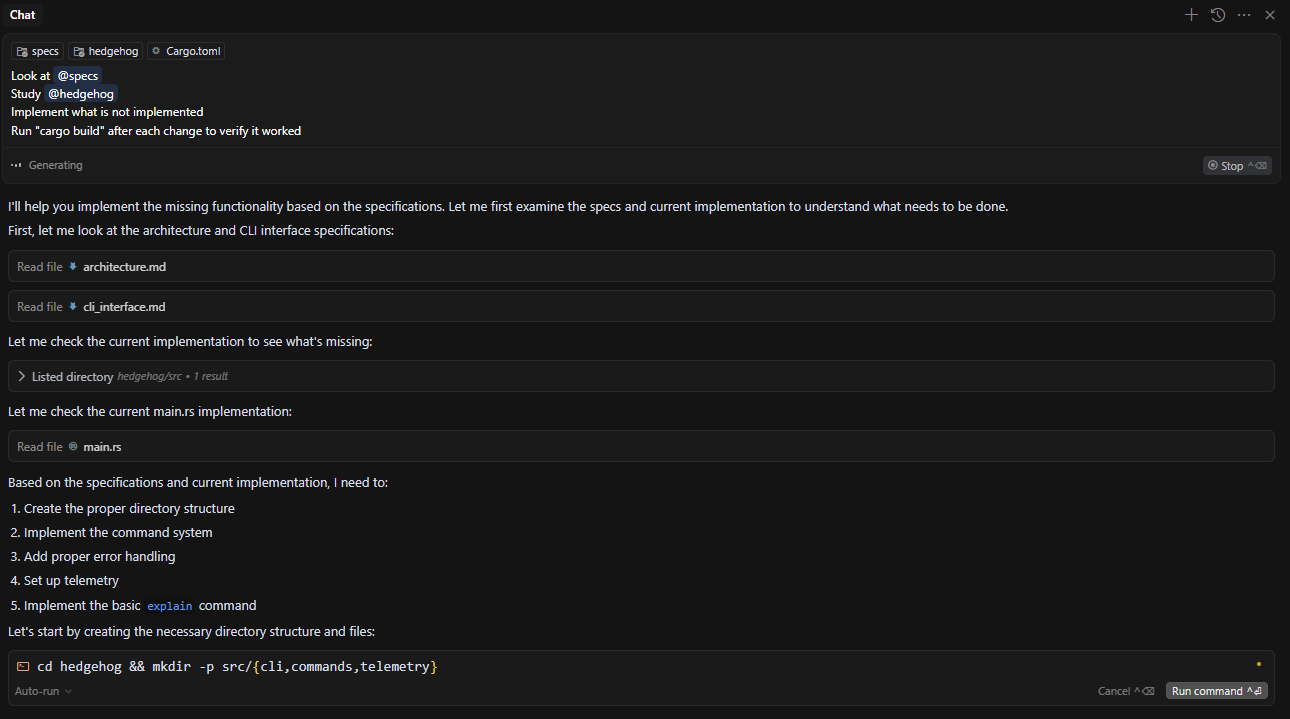

Now that the src/core has been implemented. It's time to move on to the other specification domains, such as src/ai/mcp_tools and src/ui . Start a new Cursor compose window and repeat the defining specification workflow we did at the start of the blog post.

Look at specifications in

New requirement.

What should be implemented for MCP (model context protocol) registry? Include security best practices.

What should be implemented for a new MCP (model context protocol) tool that can be invoked to list directory contents ("ls"). Include security best practices

Provide a LLM system prompt for this MCP protocol tool.

Update with this guidance. Store them under "specs/mcp" with each technical topic as a seperate markdown file.

Now, do the same for the src/ui

Look at specifications in @specs.

New requirement.

Create a basic "hello world" TUI user interface using the the "ratatui" create

Update @specs with this guidance. Store them under "specs/ui" with each UI Widget as a separate markdown file.

keep going until implemented

It's at this point you have a decision. You can launch multiple sessions of Cursor concurrently and ask each copy to chew on src/ui and src/core concurrently.

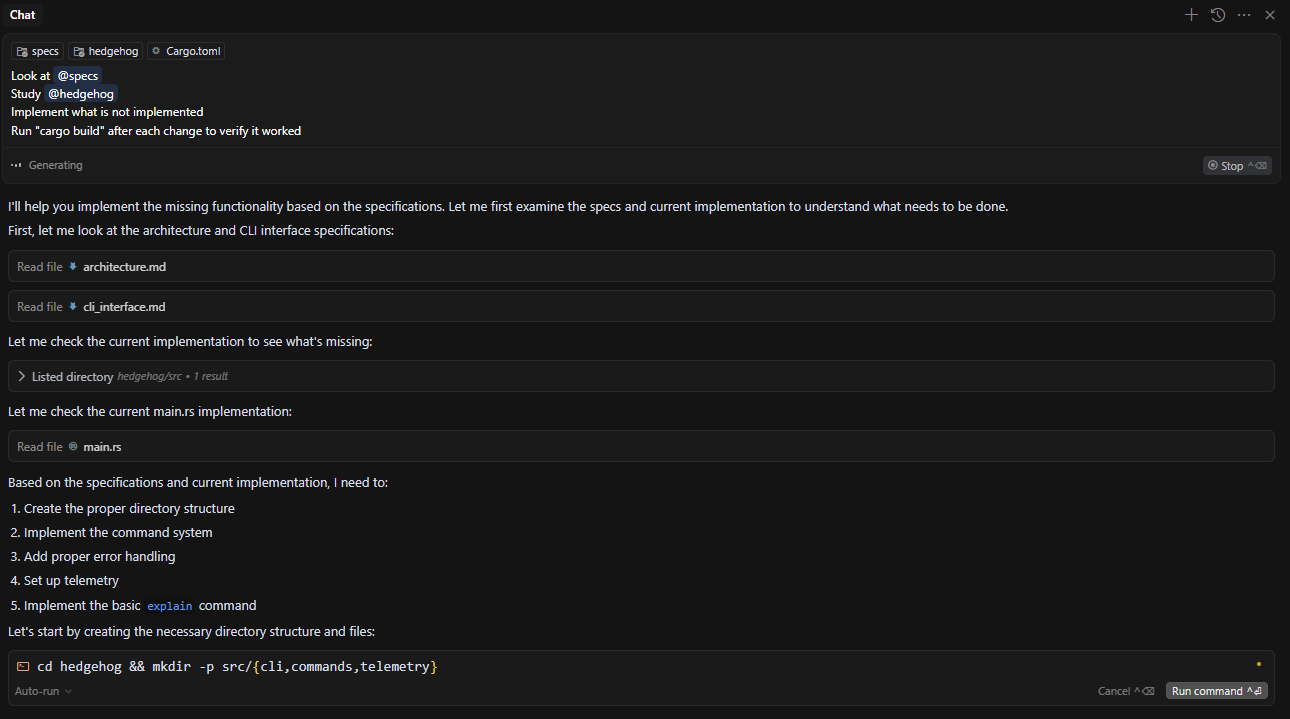

Look at @specs

Study @groundhog

Implement what is not implemented

Run "cargo build"

Run "cargo clippy"

recommendations

These LLMs work as "silly string lookup services" and have no understanding of programming languages at all. To make this all work, you are going to need a good programming language that has soundness where if it compiles, it works (ie. Rust/Haskell) and a solid property-based test suite. Rust/Haskell are unique in that they provide exceptional compiler errors, which can be looped back into the LLM to auto-fix problems until it gets it right.

The application of the "stdlib" technique to steer the LLM to use your technical requirements and via the creation of a feedback loop (ie. tests and/or a static analysis tool such as sonarqube) you are in full control of product/output quality.

The sky's the limit really - one could even hook in a pre-existing security scanning tool into the feedback loop..

closing thoughts

The limiting factor for me now is really how much screen space I have. I'm fortunate enough to have a 59" monitor on my main workstation. I can see, feel and taste the horizon of being able to ditch Cursor forever...

[

Multi Boxing LLMs

Been doing heaps of thinking about how software is made after https://ghuntley.com/oh-fuck and the current design/UX approach by vendors of software assistants. IDEs since 1983 have been designed around an experience of a single plane of glass. Restricted by what an engineer can see on their

Geoffrey HuntleyGeoffrey Huntley

Geoffrey HuntleyGeoffrey Huntley

](https://ghuntley.com/multi-boxing)

There's an approach in CompSci with compilers of "bootstrapping"

[

Bootstrapping (compilers) - Wikipedia

Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.Contributors to Wikimedia projects

Wikimedia Foundation, Inc.Contributors to Wikimedia projects

](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bootstrapping_\(compilers\)?ref=ghuntley.com)

and bootstrapping as fast as possible so Groundhog can build Groundhog is the destination we will be building towards. If you enjoyed reading, please consider subscribing to the newsletter. We are a little away from getting there, so the next part of the series will explain what the heck "MCPs" are.

The source code of Groundhog (and the stdlib + specs used to build it) can be found here. Give it a star.

[

GitHub - ghuntley/groundhog: Groundhog’s primary purpose is to teach people how Cursor and all these other coding agents work under the hood. If you understand how these coding assistants work from first principles, then you can drive these tools harder (or perhaps make your own!).

Groundhog's primary purpose is to teach people how Cursor and all these other coding agents work under the hood. If you understand how these coding assistants work from first principles, then y…

GitHubghuntley

GitHubghuntley

](https://github.com/ghuntley/groundhog?ref=ghuntley.com)

ps. socials for this blog post are below

If you enjoyed reading, give 'em a share please:

US military helicopters flying above Caracas last week. © via Reuters

US military helicopters flying above Caracas last week. © via Reuters US soldiers disembark helicopters in Vietnam in 1965 © Horst Faas/AP

US soldiers disembark helicopters in Vietnam in 1965 © Horst Faas/AP Remains of crashed US helicopters following the failed hostage rescue mission in Iran in 1980 © Bettmann via Getty Images

Remains of crashed US helicopters following the failed hostage rescue mission in Iran in 1980 © Bettmann via Getty Images