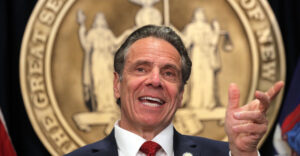

- Andrew Cuomo's March 2020 directive forced nursing homes to accept COVID-positive patients, leading to thousands of deaths, including the author's parents.

- The author's father died in a nursing home on March 29, 2020, and his mother passed away on April 14, 2020, after contracting COVID-19 in her senior-care residence.

- Cuomo's administration undercounted nursing home deaths by excluding those who died in hospitals, dismissing concerns with the callous remark, "Who cares [if they] died in the hospital, died in a nursing home? They died."

- The author recounts the heartbreaking final moments with his parents, including limited visits, rushed funeral arrangements, and a graveside service under strict pandemic restrictions.

- Five years later, the author condemns Cuomo's political comeback attempt, arguing his policies recklessly endangered vulnerable seniors when isolation was their only defense.

On 25 March, 2020, at the height of the Covid pandemic, a single piece of paper, a directive signed by Andrew Cuomo, then the governor of New York, brought about thousands of deaths in nursing homes and similar care facilities. Among the victims were my parents, Michael J. Newman and Dolores D. Newman, but known as Mickey and Dee to anyone who knew them.

My father died at a nursing home in Long Beach, and my mother died at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset after contracting Covid-19 in her senior-care residence in Far Rockaway. Her passing was recorded as a hospital fatality. We would later find out that my mom’s death along with thousands of others would be undercounted by the former governor as he infamously said, “Who cares [if they] died in the hospital, died in a nursing home? They died.”

Now, as Cuomo tries to revive his political career as the next mayor of New York City, I feel duty-bound to recall his lapse in judgment, and what it did to my family.

I first began tracking Covid in December 2019 as part of my job as a battalion chief with the Fire Department of New York City. My family was visiting my mother-in-law in Canada over the Christmas holiday, and even though I was on vacation, I couldn’t help looking at the news feeds. I read that another “flu-like” virus was causing illnesses in China, but that wasn’t out of the ordinary.

By late January 2020, it was obvious that Covid wasn’t your ordinary “flu-like” virus from the People’s Republic like SARS, say. Covid-19 was a disease that no one could hide from. It was a pandemic that would turn all our lives upside down and, in my case, result in an unbearable tragedy.

By early March, Covid was no longer an abstraction. Universities were closing. My oldest son’s concert for the Long Island String Festival Association was cancelled two days before the performance. Masks became commonplace in grocery stores and other public settings. Rumours swirled of sweeping lockdowns to come, including at nursing homes like the ones my parents lived in.

The last time I had a conversation with my father was probably 7 March, based on a photo I took from the window of the care centre, which shows massive waves crashing along the Long Beach coastline. We talked about the waves, the winter storm that sent the swell, the weather in general.

Dad had competed in road races since the 1970s as a way to stay and fit and socialise, and he was always aware of what was going on outside. I don’t recall what else we discussed, but I had no way of knowing this was to be our last chat. I visited him one more time, before the lockdowns kicked in, but he was napping, so I decided not the wake him.

I sat at his side for about 15 to 20 minutes, then tidied up his area the best I could, got a quick update from the desk nurse and left. Looking back, I was relieved that he was sleeping, because one-on-one conversations had become more taxing as his dementia progressed. I thought I was getting a one-time reprieve, and the next time I would bring Mom, who lived at a different facility nearby. The poor state of my father’s health precluded him from leaving nursing home-rehab for my mother’s senior care living centre, but the plan was to get my dad well enough to join his wife in the double room that we had secured for both of them in the assisted living residence.

I had no idea that I missed my last opportunity to talk to the man who raised me and instilled in me a love of history, athletics for sake of wellness, and personal accountability. I carry that guilt to this day.

Before the lockdown, it was hard to get my father to eat. But we had no way of knowing how much his health deteriorated behind the closed doors of the lockdown and away from the watchful eyes of visiting family members.

Daily phone calls from staff were cold and inadequate (Dad was incapable of using the phone on his own). I do remember a call I received near the end of March letting me know they were moving my father to a different floor. At the time, I didn’t think anything of it. But looking back on it now, I believe it was to make room for the Covid-positive patients, as mandated by Cuomo’s orders. As for Mom, it was much easier to say in touch; she still had her cellphone and we remained in constant contact.

The living centre that we chose for Mom was close by, and they agreed to accept Dad when he was released from rehab (Dad’s health was not good enough to be accepted at most other centres). Tragically, they were never reunited, since my father suffered a urinary-tract infection in the summer of 2019, which was the same illness that brought my mother to the hospital a month after Dad.

“I believe it was to make room for the Covid-positive patients, as mandated by Cuomo’s orders.”

On 29 March, at around 11 a.m., I received a call from a doctor at Dad’s nursing home explaining that he was running a low-grade fever and that he was lethargic. Three hours later, the same doctor called to tell me that my father had died. The call was professional and brief. To be clear, we don’t blame these facilities. They were following the governor’s health orders.

One of the hardest things I ever had to do was to call my mother and tell her that her husband of 60 years had passed. Another pressing issue was that my father’s body had to be removed within a certain number of hours, or they would be forced to send his remains the county morgue; the clock was ticking.

Our deus ex machina came in the form of a friend from the old neighbourhood in Flatbush, Brooklyn: Frankie. He was a funeral director on Staten Island and was closer in age to my older sister, Donna, who put in the call. Frankie promised to get Dad out of there before he was sent to morgue, which was significant, because these facilities were already overwhelmed with Covid patients who succumbed to the illness, and there was no way of knowing how quickly we could have gotten him out of there for a proper service.

By the early evening, Frankie let us know his nephew was going to pick up Dad and take him back to Staten Island. My sister Donna and I decided to meet him there. I called my good friend Mark, a fellow fireman, who lived nearby, and asked him to come by with whatever uniform he could muster on short notice.

I found an official FDNY sweatshirt in my house and headed over myself. We weren’t pretty, but this meant my father had an honour guard. We waited in front of the nursing home for Dad to come. We gave my father a proper salute and made sure to put his body bag in the van ourselves — a final show of respect for a man who was a military veteran and a retired member of the Fire Department, having served during one of the busiest eras of fire duty in urban history.

My dad told my mom a while back that he wished to be cremated, so Frankie handled it, and even took my dad home with him, saving me a trip to Staten Island until we figured out what to do with his ashes. An appropriate resting place for my father became available within two weeks.

I got some flowers and headed over to Mom’s care centre a couple of days after Dad passed. When I arrived, they were kind enough to let me into the lobby, as there were still no visitors allowed. I handed Mom the flowers, but didn’t hug or kiss her, as I didn’t want to infect her nor anyone else there.

We spoke through masks from 10 feet away for a few minutes, and I left. As I drove home, the song “Mickey” by Dick Robertson played on SiriusXM’s 40’s Junction station. I couldn’t remember the last time I heard that song. I would not expect Dad to be dramatic, but you never know.

As with the nursing-home rehab facility my father had been living in, Andrew Cuomo would also direct Covid-positive patients into assisted-living facilities like the one my mom was at.

About week after I saw Mom, she said that she wasn’t feeling well. Her symptoms worsened, and she was admitted to the hospital. The day she arrived, we talked several times from her cellphone as she waited in the emergency room or transfer area for a room to open up. On the evening of her second day there, we had our final conversation. The last thing she said to me was to make sure my two boys were given Easter presents on her behalf. The next day, the hospital called to say that my mother had passed away. It was 14 April.

Frankie continued his work as our angel of mercy. He organised everything he could for us. A church funeral service was out of the question with all the restrictions in place, but he was able to arrange for a burial service at Holy Cross Cemetery in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, where my family has had plots for many generations. What I didn’t anticipate was that my mother needed a dress for the burial.

Returning to the apartment where I grew up, on the top floor of the four-story walk-up, felt like strolling through a mausoleum. It was quiet and stuffy. I had been there many times since my parents entered care homes, but this visit felt suffocating. I picked out a dress and some jewellery and made my way to Frankie at his Staten Island funeral home. We hadn’t seen each other in many years, but that neighbourhood bond remained strong.

The graveside burial service was held on 18 April. The sky was grey and undecided. Flashes of light briefly broke through the clouds but never held, bathin everything around us in a sepia tone. Donna, my sister, was able to secure a priest from nearby Good Shepherd Parish to perform the service (within days, it would be it close to impossible to get a priest, what with so many people dying).

Frankie also arranged for two US Air Force airmen to attend the service and present an American flag to my family. Donna, my brother, Michael, and I decided that our niece Danielle (Donna’s daughter) should accept the flag. Danielle spent a great deal of time with my parents growing up, and it just made sense. After the service, there was no collation. We couldn’t have a lunch where we could unwind and console each other. We retreated to our respective cars, still wearing our masks, and returned to our homes. It was the best goodbye we could have hoped for, given the circumstance.

Dad and Mom were always “MickeyandDee”, as if they were one entity. The last six months of their lives in care facilities was the only time they were ever separated. Fittingly, Frankie got approval from the director of the cemetery to place Dad’s ashes in Mom’s casket. In the end, they were reunited, and they would spend eternity together, the same way they lived their lives.

Five years later, it’s important to remember that then-Gov. Cuomo’s 25 March nursing-home directive wilfully brought disease to the group least prepared to defend themselves against the novel coronavirus. Their only chance was isolation. Nursing homes and similar care centres were the keep in the castle for these seniors. They had nowhere else to run. Instead of putting up barricades and putting up a final defence, Covid was helped through the front by a decree from the man who now wants to lead Gotham.