- EvolutionaryProgress: WebAssembly Expanded From C And C Plus Plus Origins To Support Shared Memory SIMD Tail Calls And Garbage Collection

- SecondaryStatus: WebAssembly Functions As A Second Class Language On The Web Requiring JavaScript For API Access And Loading

- IntegrationBarriers: Current Designs Lack Native Integration Leading To Poor Developer Experiences And Limiting Adoption To Large Resource Rich Organizations

- WorkflowComplexity: Loading Code Is Cumbersome Without The Emerging ESM Integration Proposal Requiring Arcane JavaScript API Calls For Instantiation

- InterfaceOverhead: Interaction With Web APIs Necessitates Boilerplate Glue Code Or Bindings Which Impose Significant Runtime Costs And Complexity

- PerformanceImpact: Experimental Data Indicates That Eliminating JavaScript Glue Code In DOM Applications Can Reduce Operation Time By Forty Five Percent

- ComponentModel: The WebAssembly Component Model Proposal Aims To Provide Self Contained Artifacts With Direct Web API Support Without JavaScript

- InteroperabilityGoals: Future Components Will Allow Different Programming Languages To Link Together And Provide High Level Interfaces To JavaScript Applications

This post is an expanded version of a presentation I gave at the 2025 WebAssembly CG meeting in Munich.

WebAssembly has come a long way since its first release in 2017. The first version of WebAssembly was already a great fit for low-level languages like C and C++, and immediately enabled many new kinds of applications to efficiently target the web.

Since then, the WebAssembly CG has dramatically expanded the core capabilities of the language, adding shared memories, SIMD, exception handling, tail calls, 64-bit memories, and GC support, alongside many smaller improvements such as bulk memory instructions, multiple returns, and reference values.

These additions have allowed many more languages to efficiently target WebAssembly. There’s still more important work to do, like stack switching and improved threading, but WebAssembly has narrowed the gap with native in many ways.

Yet, it still feels like something is missing that’s holding WebAssembly back from wider adoption on the Web.

There are multiple reasons for this, but the core issue is that WebAssembly is a second-class language on the web. For all of the new language features, WebAssembly is still not integrated with the web platform as tightly as it should be.

This leads to a poor developer experience, which pushes developers to only use WebAssembly when they absolutely need it. Oftentimes JavaScript is simpler and “good enough”. This means its users tend to be large companies with enough resources to justify the investment, which then limits the benefits of WebAssembly to only a small subset of the larger Web community.

Solving this issue is hard, and the CG has been focused on extending the WebAssembly language. Now that the language has matured significantly, it’s time to take a closer look at this. We’ll go deep into the problem, before talking about how WebAssembly Components could improve things.

What makes WebAssembly second-class?

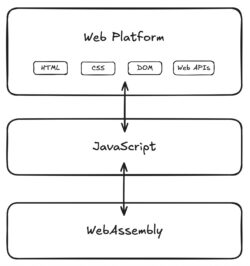

At a very high level, the scripting part of the web platform is layered like this:

WebAssembly can directly interact with JavaScript, which can directly interact with the web platform. WebAssembly can access the web platform, but only by using the special capabilities of JavaScript. JavaScript is a first-class language on the web, and WebAssembly is not.

This wasn’t an intentional or malicious design decision; JavaScript is the original scripting language of the Web and co-evolved with the platform. Nonetheless, this design significantly impacts users of WebAssembly.

What are these special capabilities of JavaScript? For today’s discussion, there are two major ones:

- Loading of code

- Using Web APIs

Loading of code

WebAssembly code is unnecessarily cumbersome to load. Loading JavaScript code is as simple as just putting it in a script tag:

<script src="script.js"></script>

WebAssembly is not supported in script tags today, so developers need to use the WebAssembly JS API to manually load and instantiate code.

let bytecode = fetch(import.meta.resolve('./module.wasm'));

let imports = { ... };

let { exports } =

await WebAssembly.instantiateStreaming(bytecode, imports);

The exact sequence of API calls to use is arcane, and there are multiple ways to perform this process, each of which has different tradeoffs that are not clear to most developers. This process generally just needs to be memorized or generated by a tool for you.

Thankfully, there is the esm-integration proposal, which is already implemented in bundlers today and which we are actively implementing in Firefox. This proposal lets developers import WebAssembly modules from JS code using the familiar JS module system.

import { run } from "/module.wasm";

run();

In addition, it allows a WebAssembly module to be loaded directly from a script tag using type=”module”:

<script type="module" src="/module.wasm"></script>

This streamlines the most common patterns for loading and instantiating WebAssembly modules. However, while this mitigates the initial difficulty, we quickly run into the real problem.

Using Web APIs

Using a Web API from JavaScript is as simple as this:

console.log("hello, world");

For WebAssembly, the situation is much more complicated. WebAssembly has no direct access to Web APIs and must use JavaScript to access them.

The same single-line console.log program requires the following JavaScript file:

// We need access to the raw memory of the Wasm code, so

// create it here and provide it as an import.

let memory = new WebAssembly.Memory(...);

function consoleLog(messageStartIndex, messageLength) {

// The string is stored in Wasm memory, but we need to

// decode it into a JS string, which is what DOM APIs

// require.

let messageMemoryView = new UInt8Array(

memory.buffer, messageStartIndex, messageLength);

let messageString =

new TextDecoder().decode(messageMemoryView);

// Wasm can't get the `console` global, or do

// property lookup, so we do that here.

return console.log(messageString);

}

// Pass the wrapped Web API to the Wasm code through an

// import.

let imports = {

"env": {

"memory": memory,

"consoleLog": consoleLog,

},

};

let { instance } =

await WebAssembly.instantiateStreaming(bytecode, imports);

instance.exports.run();

And the following WebAssembly file:

(module

;; import the memory from JS code

(import "env" "memory" (memory 0))

;; import the JS consoleLog wrapper function

(import "env" "consoleLog"

(func $consoleLog (param i32 i32))

)

;; export a run function

(func (export "run")

(local i32 $messageStartIndex)

(local i32 $messageLength)

;; create a string in Wasm memory, store in locals

...

;; call the consoleLog method

local.get $messageStartIndex

local.get $messageLength

call $consoleLog

)

)

Code like this is called “bindings” or “glue code” and acts as the bridge between your source language (C++, Rust, etc.) and Web APIs.

This glue code is responsible for re-encoding WebAssembly data into JavaScript data and vice versa. For example, when returning a string from JavaScript to WebAssembly, the glue code may need to call a malloc function in the WebAssembly module and re-encode the string at the resulting address, after which the module is responsible for eventually calling free.

This is all very tedious, formulaic, and difficult to write, so it is typical to generate this glue automatically using tools like embind or wasm-bindgen. This streamlines the authoring process, but adds complexity to the build process that native platforms typically do not require. Furthermore, this build complexity is language-specific; Rust code will require different bindings from C++ code, and so on.

Of course, the glue code also has runtime costs. JavaScript objects must be allocated and garbage collected, strings must be re-encoded, structs must be deserialized. Some of this cost is inherent to any bindings system, but much of it is not. This is a pervasive cost that you pay at the boundary between JavaScript and WebAssembly, even when the calls themselves are fast.

This is what most people mean when they ask “When is Wasm going to get DOM support?” It’s already possible to access any Web API with WebAssembly, but it requires JavaScript glue code.

Why does this matter?

From a technical perspective, the status quo works. WebAssembly runs on the web and many people have successfully shipped software with it.

From the average web developer’s perspective, though, the status quo is subpar. WebAssembly is too complicated to use on the web, and you can never escape the feeling that you’re getting a second class experience. In our experience, WebAssembly is a power user feature that average developers don’t use, even if it would be a better technical choice for their project.

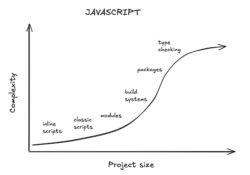

The average developer experience for someone getting started with JavaScript is something like this:

There’s a nice gradual curve where you use progressively more complicated features as the scope of your project increases.

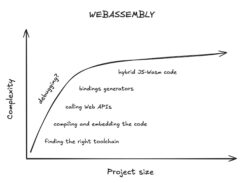

By comparison, the average developer experience for someone getting started with WebAssembly is something like this:

You immediately must scale “the wall” of wrangling the many different pieces to work together. The end result is often only worth it for large projects.

Why is this the case? There are several reasons, and they all directly stem from WebAssembly being a second class language on the web.

1. It’s difficult for compilers to provide first-class support for the web

Any language targeting the web can’t just generate a Wasm file, but also must generate a companion JS file to load the Wasm code, implement Web API access, and handle a long tail of other issues. This work must be redone for every language that wants to support the web, and it can’t be reused for non-web platforms.

Upstream compilers like Clang/LLVM don’t want to know anything about JS or the web platform, and not just for lack of effort. Generating and maintaining JS and web glue code is a specialty skill that is difficult for already stretched-thin maintainers to justify. They just want to generate a single binary, ideally in a standardized format that can also be used on platforms besides the web.

2. Standard compilers don’t produce WebAssembly that works on the web

The result is that support for WebAssembly on the web is often handled by third-party unofficial toolchain distributions that users need to find and learn. A true first-class experience would start with the tool that users already know and have installed.

This is, unfortunately, many developers’ first roadblock when getting started with WebAssembly. They assume that if they just have rustc installed and pass a –target=wasm flag that they’ll get something they could load in a browser. You may be able to get a WebAssembly file doing that, but it will not have any of the required platform integration. If you figure out how to load the file using the JS API, it will fail for mysterious and hard-to-debug reasons. What you really need is the unofficial toolchain distribution which implements the platform integration for you.

3. Web documentation is written for JavaScript developers

The web platform has incredible documentation compared to most tech platforms. However, most of it is written for JavaScript. If you don’t know JavaScript, you’ll have a much harder time understanding how to use most Web APIs.

A developer wanting to use a new Web API must first understand it from a JavaScript perspective, then translate it into the types and APIs that are available in their source language. Toolchain developers can try to manually translate the existing web documentation for their language, but that is a tedious and error prone process that doesn’t scale.

4. Calling Web APIs can still be slow

If you look at all of the JS glue code for the single call to console.log above, you’ll see that there is a lot of overhead. Engines have spent a lot of time optimizing this, and more work is underway. Yet this problem still exists. It doesn’t affect every workload, but it’s something every WebAssembly user needs to be careful about.

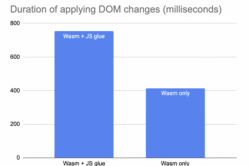

Benchmarking this is tricky, but we ran an experiment in 2020 to precisely measure the overhead that JS glue code has in a real world DOM application. We built the classic TodoMVC benchmark in the experimental Dodrio Rust framework and measured different ways of calling DOM APIs.

Dodrio was perfect for this because it computed all the required DOM modifications separately from actually applying them. This allowed us to precisely measure the impact of JS glue code by swapping out the “apply DOM change list” function while keeping the rest of the benchmark exactly the same.

We tested two different implementations:

- “Wasm + JS glue”: A WebAssembly function which reads the change list in a loop, and then asks JS glue code to apply each change individually. This is the performance of WebAssembly today.

- “Wasm only”: A WebAssembly function which reads the change list in a loop, and then uses an experimental direct binding to the DOM which skips JS glue code. This is the performance of WebAssembly if we could skip JS glue code.

The duration to apply the DOM changes dropped by 45% when we were able to remove JS glue code. DOM operations can already be expensive; WebAssembly users can’t afford to pay a 2x performance tax on top of that. And as this experiment shows, it is possible to remove the overhead.

5. You always need to understand the JavaScript layer

There’s a saying that “abstractions are always leaky”.

The state of the art for WebAssembly on the web is that every language builds their own abstraction of the web platform using JavaScript. But these abstractions are leaky. If you use WebAssembly on the web in any serious capacity, you’ll eventually hit a point where you need to read or write your own JavaScript to make something work.

This adds a conceptual layer which is a burden for developers. It feels like it should just be enough to know your source language, and the web platform. Yet for WebAssembly, we require users to also know JavaScript in order to be a proficient developer.

How can we fix this?

This is a complicated technical and social problem, with no single solution. We also have competing priorities for what is the most important problem with WebAssembly to fix first.

Let’s ask ourselves: In an ideal world, what could help us here?

What if we had something that was:

- A standardized self-contained executable artifact

- Supported by multiple languages and toolchains

- Which handles loading and linking of WebAssembly code

- Which supports Web API usage

If such a thing existed, languages could generate these artifacts and browsers could run them, without any JavaScript involved. This format would be easier for languages to support and could potentially exist in standard upstream compilers, runtimes, toolchains, and popular packages without the need for third-party distributions. In effect, we could go from a world where every language re-implements the web platform integration using JavaScript, to sharing a common one that is built directly into the browser.

It would obviously be a lot of work to design and validate a solution! Thankfully, we already have a proposal with these goals that has been in development for years: the WebAssembly Component Model.

What is a WebAssembly Component?

For our purposes, a WebAssembly Component defines a high-level API that is implemented with a bundle of low-level WebAssembly code. It’s a standards-track proposal in the WebAssembly CG that’s been in development since 2021.

Already today, WebAssembly Components…

- Can be created from many different programming languages.

- Can be executed in many different runtimes (including in browsers today, with a polyfill).

- Can be linked together to allow code re-use between different languages.

- Allow WebAssembly code to directly call Web APIs.

If you’re interested in more details, check out the Component Book or watch “What is a Component?”.

We feel that WebAssembly Components have the potential to give WebAssembly a first-class experience on the web platform, and to be the missing link described above.

How could they work?

Let’s try to re-create the earlier console.log example using only WebAssembly Components and no JavaScript.

NOTE: The interactions between WebAssembly Components and the web platform have not been fully designed, and the tooling is under active development.

Take this as an aspiration for how things could be, not a tutorial or promise.

The first step is to specify which APIs our application needs. This is done using an IDL called WIT. For our example, we need the Console API. We can import it by specifying the name of the interface.

component {

import std:web/console;

}

The std:web/console interface does not exist today, but would hypothetically come from the official WebIDL that browsers use for describing Web APIs. This particular interface might look like this:

package std:web;

interface console {

log: func(msg: string);

...

}

Now that we have the above interfaces, we can use them when writing a Rust program that compiles to a WebAssembly Component:

use std::web::console;

fn main() {

console::log(“hello, world”);

}

Once we have a component, we can load it into the browser using a script tag.

<script type="module" src="component.wasm"></script>

And that’s it! The browser would automatically load the component, bind the native web APIs directly (without any JS glue code), and run the component.

This is great if your whole application is written in WebAssembly. However, most WebAssembly usage is part of a “hybrid application” which also contains JavaScript. We also want to simplify this use case. The web platform shouldn’t be split into “silos” that can’t interact with each other. Thankfully, WebAssembly Components also address this by supporting cross-language interoperability.

Let’s create a component that exports an image decoder for use from JavaScript code. First we need to write the interface that describes the image decoder:

interface image-lib {

record pixel {

r: u8;

g: u8;

b: u8;

a: u8;

}

resource image {

from-stream:

static async func(bytes: stream<u8>) -> result<image>;

get: func(x: u32, y: u32) -> pixel;

}

}

component {

export image-lib;

}

Once we have that, we can write the component in any language that supports components. The right language will depend on what you’re building or what libraries you need to use. For this example, I’ll leave the implementation of the image decoder as an exercise for the reader.

The component can then be loaded in JavaScript as a module. The image decoder interface we defined is accessible to JavaScript, and can be used as if you were importing a JavaScript library to do the task.

import { Image } from "image-lib.wasm";

let byteStream = (await fetch("/image.file")).body;

let image = await Image.fromStream(byteStream);

let pixel = image.get(0, 0);

console.log(pixel); // { r: 255, g: 255, b: 0, a: 255 }

Next Steps

As it stands today, we think that WebAssembly Components would be a step in the right direction for the web. Mozilla is working with the WebAssembly CG to design the WebAssembly Component Model. Google is also evaluating it at this time.

If you’re interested to try this out, learn to build your first component and try it out in the browser using Jco or from the command-line using Wasmtime. The tooling is under heavy development, and contributions and feedback are welcome. If you’re interested in the in-development specification itself, check out the component-model proposal repository.

WebAssembly has come very far from when it was first released in 2017. I think the best is still yet to come if we’re able to turn it from being a “power user” feature, to something that average developers can benefit from.