- Company Valuation: Code Metal reached a 1.25 billion dollar valuation following a 125 million dollar Series B funding round in February 2026.

- Core Technology: The platform utilizes artificial intelligence to translate legacy defense software into modern programming languages like Rust, VHDL, and CUDA.

- Formal Verification: The system employs mathematical formal verification to prove that translated code behaves identically to the original, aiming for zero-error compliance with flight safety standards.

- Market Demand: The Department of Defense faces a 66 billion dollar annual IT challenge, with 60 to 70 percent of software budgets dedicated to maintaining aging legacy systems.

- Labor Shortage: Military infrastructure relies on outdated languages such as Ada, Fortran, and COBOL, while the original programmers are reaching retirement age without available replacements.

- Strategic Leadership: The firm is led by veterans of BAE Systems and MIT Lincoln Laboratory and has recruited executive talent from Salesforce and the National Security Council.

- Client Portfolio: Major defense contractors and entities, including L3Harris, RTX, and the U.S. Air Force, have engaged the company to modernize mission-critical systems.

- Scalability Risks: While effective in pilot programs, the mathematical verification method faces unproven technical hurdles when applied to undocumented, million-line codebases.

A decade ago, Peter Morales sat inside a BAE Systems office trying to solve a problem that would later make him a billionaire on paper. Engineers on the F-35 program had written machine-learning algorithms in MATLAB, MathWorks's programming environment, to recognize and jam enemy radar. The algorithms worked fine in the lab. Getting them to run on the fighter's actual onboard chips was another matter entirely.

"They developed some cool machine-learning algorithms and they needed help getting this running in real time," Morales told the Boston Globe in 2024. The gap between writing code that works in a lab and deploying it on hardware that flies at Mach 1.6 consumed months of painstaking manual translation. Every line rewritten by hand introduced risk, and every risk required testing. Months of it. Time that defense procurement officials did not have.

That frustration became Code Metal, a Boston startup now valued at $1.25 billion after closing a $125 million Series B in February 2026. The company's pitch is deceptively simple: use AI to translate code between programming languages, then mathematically prove the translation is correct. A wrong line of code in a commercial app means a crash and a patch. In defense software, it can mean a grounded fleet or a breached satellite link.

The central question for Code Metal is not whether verified code translation has value. The Pentagon has already answered that. What nobody knows yet is whether Code Metal's method holds up when you throw it at the sprawling, decades-old codebases that actually run American military infrastructure. Pilot programs are one thing. Production is something else.

The Breakdown

- Code Metal raised $125M Series B at $1.25B valuation, claims profitability with L3Harris, RTX, and Air Force as customers

- AI translates legacy defense code (Ada, COBOL, Fortran) into modern languages, then uses formal verification to prove correctness

- Pentagon spends $66B yearly on IT, with 60-70% going to maintain legacy systems written in languages losing their last programmers

- Key risk: formal verification has never been proven at scale on million-line, decades-old, undocumented codebases

A trillion dollars of technical debt

How bad is it? The F-35 alone runs on somewhere between 8 and 24 million lines of code, depending on who's counting and whether you include the ground-based logistics suite. C, C++, and Ada, that last one a language the DoD mandated in the 1980s because it seemed like a good idea at the time. Congressional testimony put the F-35's software bill at roughly $16.4 billion between fiscal years 2018 and 2024.

That is one weapons system. The Pentagon's total IT budget request for fiscal 2026 hit $66 billion, up $1.8 billion from the year before. Its cyber budget alone hit $15 billion. Some estimates put military software maintenance at 60 to 70 percent of total software budgets. Sixty to seventy cents of every dollar, spent keeping old systems breathing rather than building new capability. It is an embarrassing ratio for an organization that bills itself as the most technologically advanced fighting force on earth.

The human problem is worse than the financial one, and the Pentagon knows it. Ada, Fortran, COBOL. The people who wrote those languages into Pentagon systems three and four decades ago are heading for retirement. Their knowledge walks out with them, and nobody is lining up to replace them. Try posting a job listing for a COBOL specialist willing to maintain satellite communications protocols. See who applies.

Washington gets this, at least on paper. The DoD's Software Modernization Implementation Plan for 2025-2026 calls for software factories, cloud migration, legacy overhaul. The Army wants a whole new budget line, BA-8, built around software rather than the hardware-first model the Pentagon has run on for decades. Plans exist. A fast, safe way to actually convert millions of lines of legacy code does not.

How the machine works

Code Metal builds a translation engine. You feed it code in Python, Julia, MATLAB, or C++. Out the other end comes Rust, VHDL, Nvidia's CUDA, whatever the target hardware demands. The translation runs in phases. The system first analyzes the source codebase to identify what each component does. It generates a translation plan. Then a combination of large language models and traditional code-processing methods rewrites the software in the target language.

That description fits dozens of AI coding tools on the market. What Code Metal sells as its difference is the verification layer.

At each translation step, the platform generates test harnesses, automated containers of data and evaluation tools, that check whether the new code behaves identically to the original. The company uses formal verification, a mathematical method that maps every possible state of a program to prove correctness rather than merely testing for common failure modes. Code Metal claims compliance with MC/DC, the Modified Condition/Decision Coverage standard used to evaluate flight control software.

"There's no way to generate an error," Morales told WIRED. "The software will just say, 'There's no solution for this' if we can't complete the translation."

That is a strong claim. It means Code Metal would rather refuse a job than produce flawed output, a posture that maps well onto defense procurement culture, where the cost of a wrong answer dwarfs the cost of a slow one.

B Capital partner Yan-David Erlich, an investor in the Series B, put it without polish. The code that controls satellites and communications infrastructure "is old, it's crufty, it's written in programming languages that people might not use anymore. It needs to be modernized. But in the course of translation, you might be inserting bugs, which is catastrophically problematic."

The investor thesis boils down to timing. AI can now generate code fast enough to matter, and the defense industry is desperate enough to buy. B Capital has a phrase for this, "verified intelligence," and the logic is straightforward. AI is embedding itself deeper into infrastructure where mistakes kill people. The bar has to move from plausible output to provable correctness. There is no middle ground.

From seven employees to unicorn in twenty months

The funding trajectory does not look like a normal startup. It looks like a defense contractor sprinting toward a program of record.

They incorporated in 2023 with seven people and a $16.5 million seed from J2 Ventures and Shield Capital by July 2024. Accel came in at $36.5 million for the Series A that November, valuing the company at $250 million after hearing about eight-figure revenue. Three months later Salesforce Ventures wrote the $125 million Series B check. Valuation jumped to $1.25 billion. Fivefold in ninety days. That is not a normal trajectory.

Code Metal says it is already profitable and cash-flow positive. No audited financials to back that up, but if true, the company is a genuine outlier in an AI startup world that mostly burns cash and worries about margins later. The company has not disclosed specific revenue figures, but the phrase "eight-figure revenue" at the Series A stage and profitability at the Series B stage suggest a business model tied to large government and industrial contracts rather than high-volume, low-margin SaaS.

The customer list tells you where the money comes from. L3Harris, RTX (formerly Raytheon), the Air Force, Toshiba, Robert Bosch. Code Metal says some of those clients went from months-long deployment timelines to days. It is also in talks with a "large chip company" for code portability work across processor platforms, though it declined to name the firm.

The operators tell the story

Code Metal's recent appointments point in two directions at once.

Get Implicator.ai in your inbox

Strategic AI news from San Francisco. No hype, no "AI will change everything" throat clearing. Just what moved, who won, and why it matters. Daily at 6am PST.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Ryan Aytay joined as president and chief operating officer. He spent 19 years at Salesforce, rising to chief business officer under CEO Marc Benioff before running Tableau as CEO from 2023 until his departure in early 2026. Aytay's background is enterprise sales and partnerships at massive scale. He managed Salesforce's strategic relationships with Amazon, Google, Apple, and IBM. You don't hire a former Tableau CEO to run a seven-person Boston startup unless you're building a sales operation that can handle decade-long procurement cycles and the relationship-heavy politics of defense contracting.

Then there's Laura Shen, executive vice president of growth, who used to run the China desk at the U.S. National Security Council. That hire says something about where Code Metal sees its next contracts coming from. Not just the Pentagon.

The founding team carries its own weight. Morales built AI reasoning systems for the F-35. He spent years at MIT Lincoln Laboratory working on counter-drone defense for the U.S. Capitol, and later moved to Microsoft to develop computer vision for HoloLens. CTO Alex Showalter-Bucher, also a Lincoln Lab alumnus, spent a decade across the Navy, Army, and Department of Homeland Security. The engineering bench draws from Intel, NASA, MathWorks, Lightmatter, and OpenAI.

Nobody on this team learned about defense software from a pitch deck. They were in the rooms where legacy code caused real problems, watching engineers spend months on translation work that produced more anxiety than confidence. Talk to Morales long enough and you hear that frustration in every answer. It is not a talking point. It is the reason the company exists.

The gap between proof of concept and proof at scale

Formal verification is not new. If you have been anywhere near defense procurement, you have seen it. Aerospace engineers and nuclear weapons designers have used it for decades to certify safety-critical software. Old technique. Code Metal's bet is that AI can bring the cost down far enough to make it practical outside those narrow, well-funded niches.

The catch is obvious. Formal verification works when the program is small and well-defined. Hand it a million-line legacy codebase, three decades of accumulated decisions by rotating teams working in multiple languages, half of it never documented? That is a different animal entirely. Nobody has proved formal verification scales to that kind of mess.

Code Metal won't say much about how it actually works. WIRED called the company "skittish about sharing too many details," and that tracks. Competitive secrecy makes sense when your moat is methodology, but it also means outsiders can't verify the claims. Zero errors in current pipelines? Maybe. For the controlled translation tasks the company has run so far, that could well be true. The question is what happens when the codebases get bigger, older, and tangled in ways nobody documented at the time.

Look at the broader AI coding market for context. The best code generation models in 2025 hit somewhere between 70 and 82 percent accuracy on common programming languages. Performance remains, as one AI safety report put it, "jagged," with leading systems still failing at some tasks that appear straightforward. Code Metal's proposition is that its neuro-symbolic approach, combining LLMs with formal methods, overcomes these limitations. The formal verification layer acts as a filter: if the AI hallucinates, the math catches it.

That architecture sounds compelling. But the company's own pricing model hints at the difficulty. Morales told WIRED that Code Metal negotiates pricing individually with each customer based on time to develop a kernel, lines of code translated, or development time saved. He acknowledged the process "can get murky." When the vendor acknowledges murkiness, the product is still finding its shape.

What Code Metal reveals about defense procurement

Defense technology meant hardware for decades. Jets, ships, missiles. Software? A cost center bolted onto the side of weapons programs. The F-35's budget categories still treat it that way, which is exactly why the Army wants BA-8, a funding line that treats software like what it actually is rather than an afterthought stapled to airframes.

Code Metal lives in the gap between those two worlds. Its customers are defense contractors and military branches that know their software needs modernizing but cannot do the work themselves fast enough. The pitch is speed without recklessness. Anduril and Palantir already proved that venture-backed companies could win Pentagon contracts. Code Metal is chasing something less visible but possibly bigger. The plumbing.

Autonomous drones get the headlines. Nobody writes breathless profiles about translating a thirty-year-old satellite protocol from Ada to Rust. But keeping legacy infrastructure alive while slowly dragging it into modern standards, that boring work might be worth more in total addressable market than any single new weapons system.

Rob Keith at Salesforce Ventures, who led the Series B, put it in procurement language. "AI code generation has hit an inflection point," he said. "Mission-critical industries cannot deploy what they cannot verify." Venture-capital polish aside, he's right about the core problem. The bottleneck in defense AI is not generation. It is trust.

The test

Code Metal started because getting working algorithms onto actual hardware took too long and broke too often. Whether the company can repeat that fix at orders of magnitude greater scale is the whole bet.

The pilots are done. L3Harris, RTX, and the Air Force are named customers. Morales says every pilot deployment has advanced to the next phase. The Series B gives Code Metal the capital to staff up, with Aytay running operations and Shen working growth channels that extend into national security policy.

Now comes the hard part. Converting pilot contracts into programs of record, the multiyear, multimillion-dollar deals that actually sustain defense technology companies. Not demos. Not proofs of concept. Production contracts that survive procurement cycles measured in decades.

That conversion will stress-test everything. Can formal verification hold at scale? Can the pricing model withstand government auditors? And can a startup founded in 2023 earn the kind of institutional trust that defense procurement demands, the kind that usually takes a decade to build?

The F-35's codebase took decades to accumulate. Modernizing it will take years no matter who does the work. Code Metal's $1.25 billion valuation says the market thinks the company can compress that timeline dramatically. The next twelve months will tell. Either the early contracts expand into production, or they stall in review. The math does not care about the valuation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does Code Metal actually do?

Code Metal uses AI to translate software from one programming language to another, then applies formal verification to mathematically prove the translated code behaves identically to the original. Its primary customers are defense contractors and military branches modernizing legacy systems.

What is formal verification and why does defense need it?

Formal verification is a mathematical method that checks every possible state of a program to prove correctness, rather than just testing for common failures. Aerospace and nuclear engineers have used it for decades. For military software, a single bug can ground a fleet or breach a satellite link, making proof-based testing worth the cost.

How did Code Metal reach a $1.25 billion valuation so fast?

The company incorporated in 2023 and raised a $16.5 million seed by mid-2024. Accel led a $36.5 million Series A in November 2025 at $250 million. Salesforce Ventures then wrote the $125 million Series B check three months later. The company claims eight-figure revenue and profitability, though it has not released audited financials.

Who are Code Metal's main competitors?

Dozens of AI coding tools exist, but most focus on code generation without verified correctness. Code Metal's closest competitive space includes general AI code translation tools, but its formal verification layer targets a different buyer: organizations where incorrect code has catastrophic consequences. Defense primes like L3Harris and RTX are customers, not competitors.

What is the biggest risk to Code Metal's business?

Scaling formal verification to massive legacy codebases. The technique works well on small, well-defined programs. Pentagon systems involve millions of lines written over decades by rotating teams in multiple languages, much of it undocumented. Nobody has proven formal verification works reliably at that scale. The company also maintains secrecy about its methods, making independent evaluation difficult.

[

Pentagon Threatens Anthropic With Supply Chain Risk Label Over Military AI Limits

The Pentagon is preparing to designate Anthropic as a "supply chain risk" and sever business ties with the AI company over its refusal to allow unrestricted military use of Claude, Axios reported on M

The Implicator

](https://www.implicator.ai/pentagon-threatens-anthropic-with-supply-chain-risk-label-over-military-ai-limits/)

[

Pentagon Targets Anthropic. India Writes the Checks.

San Francisco | Tuesday, February 17, 2026 The Pentagon is close to labeling Anthropic a supply chain risk. Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth wants Claude available for "all lawful purposes." Anthropic

The Implicator

](https://www.implicator.ai/pentagon-targets-anthropic-india-writes-the-checks/)

[

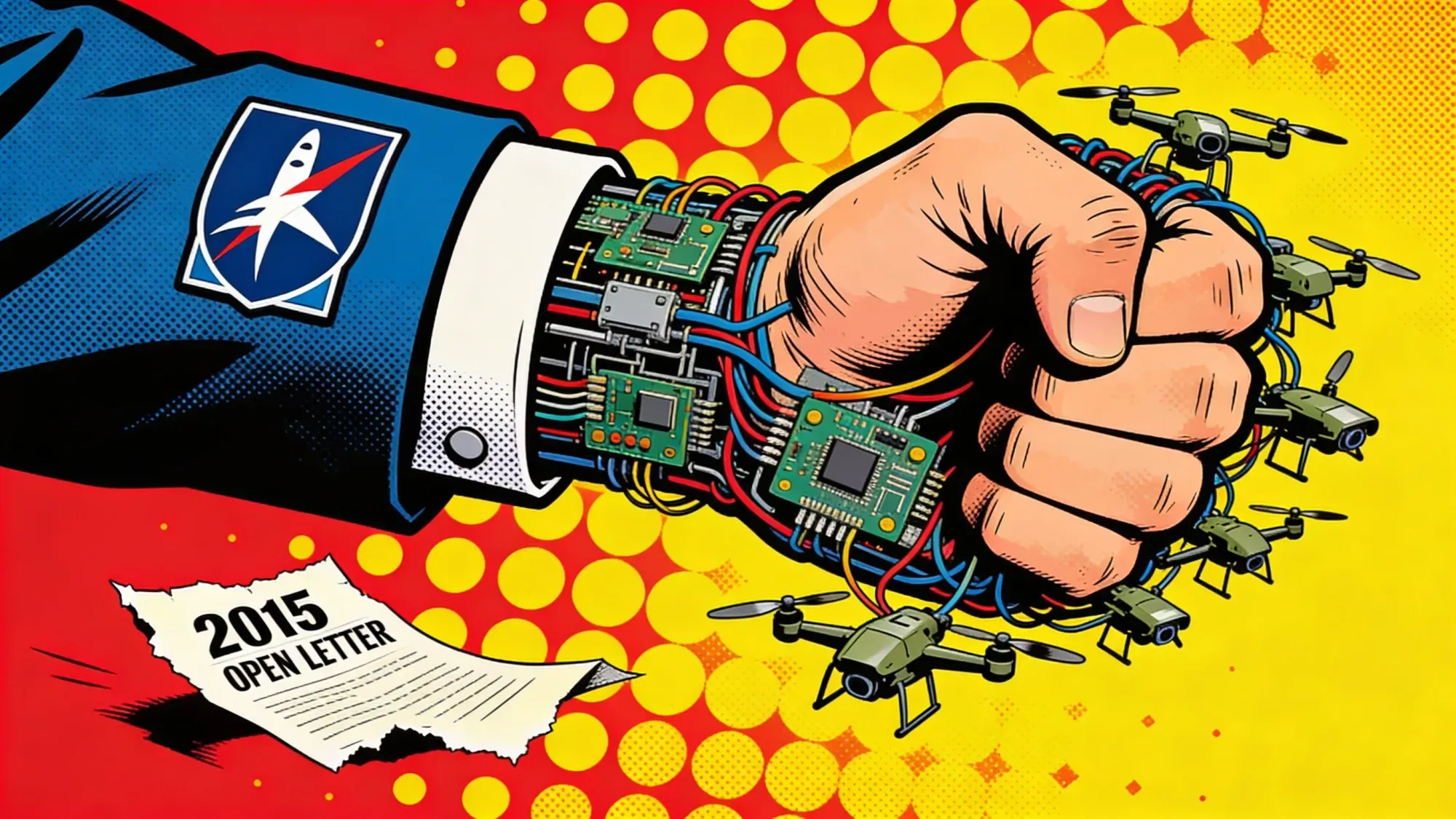

SpaceX and xAI Enter Secret $100M Pentagon Contest for Autonomous Drone Swarms

SpaceX and its subsidiary xAI are competing in a secret Pentagon contest to build voice-controlled autonomous drone swarming technology, Bloomberg reported Sunday. The $100 million prize challenge, la

The Implicator

](https://www.implicator.ai/spacex-and-xai-enter-secret-100m-pentagon-contest-for-autonomous-drone-swarms/)

A mock Breitling shop on display at the headquarters of Partners Group in Zug, Switzerland © Alexandra Heal/FT

A mock Breitling shop on display at the headquarters of Partners Group in Zug, Switzerland © Alexandra Heal/FT